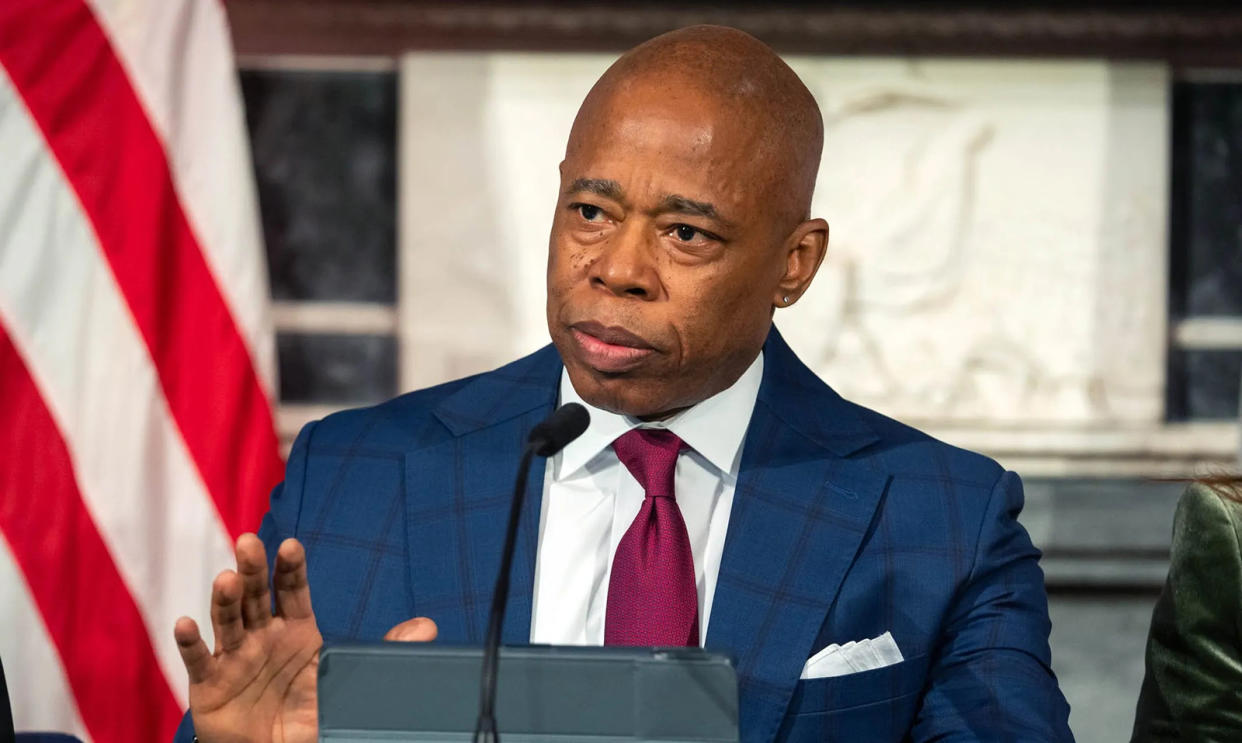

Legal Aid to sue Adams admin for not implementing new housing voucher laws: ‘It could help a lot of people’

NEW YORK — The Legal Aid Society is gearing up to file a lawsuit in coming weeks seeking to force City Hall to implement a legislative package that would expand access to a rental voucher program that helps low-income New Yorkers afford permanent housing.

The City Council package — which Mayor Adams opposes because he says the chamber passed it without identifying a funding stream — consists of several bills designed to overhaul the so-called CityFHEPS voucher program. Chief among the reforms is a measure that would abolish a rule requiring low-income New Yorkers to enter a city shelter before they can apply for the program, which subsidizes rent on open market apartments.

After the Council passed the bills last summer amid the city’s ongoing housing crisis, Adams vetoed them, citing concerns over the cost of implementation. But the Council successfully voted in July to override the veto, enacting the bills against Adams’ will, with the new laws set to officially take effect Tuesday.

Nonetheless, Adams’ office told Council leaders in a letter last month he wouldn’t implement the reforms by the deadline due to “financial, operational and legal issues” — and Legal Aid attorney Robert Desir says his group is now drafting a lawsuit that will ask a judge to order the administration to start following the new CityFHEPS laws as written.

“A fiscal argument doesn’t override a duly enacted law,” Desir told the Daily News in a recent interview. “That doesn’t suffice as a legal defense.”

Aware that a lawsuit was likely imminent, the Adams team’s letter from last month said “in the event of litigation,” the mayor has “arguments founded in law and public policy” for why he shouldn’t have to enact the CityFHEPS reforms.

Asked Monday to elaborate on those arguments, Adams referred to his Law Department, which didn’t return a request for comment.

Adams spokeswoman Kayla Mamelak later issued a statement referencing a projection from Adams’ budget analysts finding the bills would add $17 billion in new costs over the next five years — an expense the mayor says the city can’t afford at a time when it’s spending hundreds of millions of dollars on housing migrants every month.

Desir, whose group has joined Council Democrats in dismissing City Hall’s cost projections as exaggerated, said he’s in the midst of finalizing the selection of the lawsuit’s plaintiffs and will file in Manhattan Supreme Court in coming weeks. Legal Aid may seek class action status for the suit to represent all low-income New Yorkers living in shelters as well as those on the brink of homelessness who would become eligible for vouchers under the Council bills, Desir added.

Also Tuesday, Council Speaker Adrienne Adams sent a letter to Department of Social Services Commissioner Molly Wasow Park saying the Council will pursue legal action as well if the administration doesn’t take “concrete, verifiable steps” by Feb. 7 to implement the new CityFHEPS laws.

“Every day DSS delays in implementing the laws is a day that more New Yorkers needlessly end up or remain in homeless shelters, and the city faces unnecessary legal liability,” the speaker wrote to Wasow Park, whose agency oversees the CityFHEPS program.

It was not immediately clear if the Council would pursue its own lawsuit or join Legal Aid’s filing.

Though he’s not under consideration to be a named plaintiff in Legal Aid’s suit, Dane Warren, a formerly homeless health care worker, told The News last week he’s in favor of pushing Adams to implement the Council reforms.

Warren, who’s 57 and had to stop working due to a disability, became homeless after his mother died and he could no longer afford rent on their apartment. He said he spent more than a year in city shelters before being able to move into his current Bronx apartment this past October after finally being cleared for a CityFHEPS voucher that covers his entire rent.

Had the new Council laws been in place when his mom died, Warren said, he believes he wouldn’t have had to enter the shelter system as he could’ve stayed in his apartment while applying for a voucher.

“It will prevent people from being displaced like I was,” he said of the Council bills. Addressing Adams, Warren added: “At least test it out. It could help a lot of people.”

Before vetoing the Council’s bills, Adams issued an executive order that eliminated the so-called 90-day rule, which required that CityFHEPS applicants stay in a shelter for three months before they could file a claim for a voucher.

He signed the order only after the Council had already passed its CityFHEPS package, which includes a measure repealing the 90-day rule.

On top of the 90-day rule rollback, the package features a measure that would make anyone “at risk of eviction,” including someone who receives a rent demand from a landlord, eligible for a voucher as long as they meet certain other requirements, like being a low-income earner. To further expand access, the Council package would also scrap a rule requiring CityFHEPS applicants to work a certain number of hours a week and increase the household income cutoff for eligibility from 200% of the federal poverty level to 50% of area median income.

Adams opposes, due to fiscal concerns, all the provisions beyond the elimination of the 90-day rule. The Council’s own fiscal statement doesn’t identify a funding stream for the $3.3 billion its budget analysts say the reforms would cost over the next five years.

Still, Desir said the mayor’s argument misses the mark.

He contended that making it easier to access CityFHEPS could actually generate savings in the long run, pointing to studies that show it’s on average more expensive for the city to house a family of three in a shelter than to pay for a voucher that covers rent on an apartment.

Desir also said there’s a ripple effect of fiscal and social pressure that’s tough to calculate that comes from requiring New Yorkers to enter a shelter before being able to apply for CityFHEPS.

“It’s a major disruption, especially if there’s a child and accommodations have to be made for them to get to school,” he said. “It’s really a significant hardship on a family.”