Perak-born woman becomes Malaysian citizen at 68, fulfilling late husband’s wishes

KUALA LUMPUR, Sept 29 — A Perak-born stateless woman is overjoyed to finally be officially recognised as a Malaysian at the age of 68, after collecting her proof of Malaysian citizenship and her blue Malaysian identity card — otherwise known as MyKad and only issued to Malaysian citizens — just a few days after Malaysia Day.

Having lived in Malaysia her whole life but without a citizenship from any country, the woman — whose name is being withheld to protect her privacy — is “excited, joyful and moved” to finally be recognised a Malaysian citizen, her children told Malay Mail.

“It’s like a dream come true,” her children said when asked how she felt. They responded to Malay Mail via the woman’s lawyer Larissa Ann Louis.

As for what was most meaningful to her for Malaysia to finally recognise her as a citizen, the children said: “She would no longer have to feel different than other people who have blue identity card, she’s proud to say she’s truly Malaysian now. And she could fulfil our late father’s wish too.”

The woman’s husband, who himself died as a stateless person about seven years ago, had wished for her to be recognised as a citizen of Malaysia.

As for her children who are all Malaysians, they said they were “definitely happy for her as she’s finally a Malaysian citizen now, she can live life as a normal Malaysian, enjoy all the benefits given by our government and able to vote soon.”

The very first thing that the woman wanted to do after getting a Malaysian identity card was to get a Malaysian passport, which she did on the same day as her collection of the MyKad at the National Registration Department’s (NRD) Putrajaya headquarters.

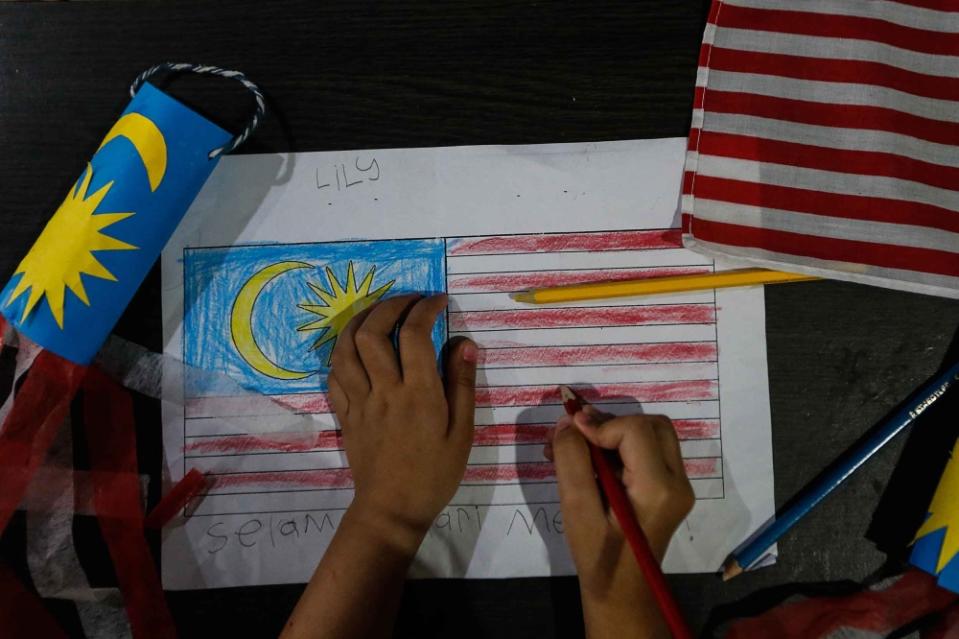

Previously, the woman told the High Court that she had suffered emotionally, as she had been mocked for being of ‘Bukan Warganegara’ (non-citizen) status and was frequently ridiculed as purportedly being a ‘foreigner’. — Picture by Sayuti Zainudin

Her long path to citizenship

The woman never knew the biological parents who abandoned her after she was born in a Perak hospital in 1955, and has no records of their nationality and only knows their names from her birth certificate. She was born before Malaya became independent on August 31, 1957 (Merdeka Day) and before Malaysia’s formation on September 16, 1963 (Malaysia Day).

Her Malaysian adoptive parents — who cared for her since birth and legally adopted her at age nine — are now deceased.

Previously, the woman told the High Court that she had suffered emotionally, as she had been mocked for being of “Bukan Warganegara” (non-citizen) status and was frequently ridiculed as purportedly being a “foreigner”. This is despite her not being a citizen of any other country.

She had to work during her teenage years to survive as times were hard. Having married at age 19 to her stateless husband who had permanent resident status, the woman had never thought about her own citizenship status while fully focused on raising their seven children.

When her youngest child had grown up, the woman then applied to the NRD in March 2007 for permanent resident status, which she successfully obtained in April 2007.

After applying to the NRD for Malaysian citizenship on December 19, 2017, the Home Ministry in an August 23, 2022 letter informed her that her application was rejected but did not give any reasons.

Her citizenship application was made under the Federal Constitution’s Article 19, which required proof that she had stayed in Malaysia for 10 years before applying to be a Malaysian citizen by naturalisation. Her PR status from 2007 to 2017 would enable her to prove this.

Under Article 19, the Malaysian government may choose to approve applications to be a naturalised citizen if satisfied that the applicant aged at least 21 is of “good character”, has “adequate knowledge” of the Malay language, has lived in Malaysia at least 10 years — within 12 years before the application — and intends to live permanently in Malaysia if naturalised.

Under Article 19, the Malaysian government may choose to approve applications to be a naturalised citizen if satisfied that the applicant aged at least 21 is of ‘good character’, has ‘adequate knowledge’ of the Malay language, has lived in Malaysia at least 10 years — within 12 years before the application — and intends to live permanently in Malaysia if naturalised. — Picture by Sayuti Zainudin

A court challenge and successful second citizenship attempt

On November 22, 2022, the woman filed a lawsuit in the High Court against the Home Ministry secretary-general, the National Registration Department director-general, and the government of Malaysia, and sought to be declared a Malaysian citizen and be issued a citizenship certificate and the MyKad identity card.

As her court case was filed through an application for judicial review, the court had to first grant leave or permission for the lawsuit to be heard.

The High Court on January 4 this year granted her leave as there were no objections by the Attorney-General’s Chambers (AGC).

When contacted, Larissa told Malay Mail that the government on June 20 suggested that her client could apply for Malaysian citizenship under the Federal Constitution’s Article 16.

Malay Mail’s check of the Federal Constitution shows that Article 16 caters specifically to those born in Malaysia before Merdeka Day in 1957, where they can be registered as a Malaysian citizen if they apply and can satisfy the Malaysian government that they meet these conditions: have lived in Malaysia for at least five years within a seven-year period immediately before applying; intends to live in Malaysia permanently; is of “good character”, and has “elementary knowledge” of the Malay language.

Larissa said the woman on July 5 made a citizenship application under Article 16 at the NRD’s Jalan Duta office and was interviewed the next day at the same office.

Larissa said the AGC on August 8 informed her that the NRD had approved her client’s Article 16 citizenship application, and that her client on September 19 collected her certificate of citizenship and identity card at the NRD’s Putrajaya office.

Previously, High Court judge Datuk Ahmad Kamal Md Shahid had on July 31 heard the woman’s lawsuit. At that time, the woman was still waiting for the NRD’s decision on her Article 16 application.

On September 26, which was when the High Court was scheduled to deliver its decision on the woman’s court challenge, the judge was informed that the woman’s citizenship application under Article 16 had been approved.

Asked by Malay Mail, Larissa confirmed that the High Court did not deliver a decision as her client has been recognised as a Malaysian citizen. Her client sought to withdraw the case and the High Court then made an order of withdrawal of the case with no order as to costs.

Click here for more about the Perak woman’s story and her court case.

Lawyer Larissa Ann Louis speaks to reporters at the Kuala Lumpur High Court January 4, 2023. — Picture by Miera Zulyana

Why the Perak woman’s pre-Merdeka case is important

Larissa was sad that her 68-year-old client had to wait so many years before she was recognised as a Malaysian under the law.

“It’s indeed sad that it had to take a case to be filed in court to get Malaysian citizenship less than two months from an application — a citizenship which should have been hers long ago. We often have to file cases in court to get the attention of the relevant ministries. However, not every stateless person has the relevant resources to do so.

“I am very glad she’s a citizen finally and thankful to the government for suggesting an alternative route i.e. via Article 16 for her. However, I am saddened by the fact that we could not set a precedent in court on Article 14(1)(a) and Article 19, an inaugural attempt in court,” the lawyer told Malay Mail.

The Perak woman is believed to be the first person to file a court challenge against both the Malaysian government’s rejection of Article 19 applications to be a naturalised citizen and on Article 14(1)(a) which contains the pathway for persons born before Malaysia Day in 1963 to be entitled to be a Malaysian citizen. In other words, Article 14(1)(a) covers individuals who were born before Malaysia was even formed.

Article 14(1)(a) requires conditions under Part I of the Federal Constitution’s Second Schedule to be fulfilled for such pre-Malaysia born persons to be Malaysians.

In the Perak woman’s lawsuit, she had argued that she meets the condition under Section 1(1)(a) of Part I of the Second Schedule to be a Malaysian citizen, namely that she was — immediately before Merdeka Day in 1957 — a citizen of the Federation of Malaya, based on the Federation of Malaya Agreement 1948.

(Malaya — which is now known as peninsular Malaysia — declared its independence in 1957 and came together with Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore in 1963 to form Malaysia.)

She had through her lawyer argued that she fulfills either clause 125(a) or 125(c) of the Federation of Malaya Agreement 1948 to be a citizen of then-Malaya under the law, namely that she was either a subject of the ruler of any state (Perak in her case) or she was born in Malaya and born a citizen of the UK and colonies and that one of her parents was born in Malaya.

The outcome of those arguments based on pre-Merdeka laws and pre-Merdeka situations are now unknown, as she received her citizenship recognition before a court decision was delivered.

In the Perak woman’s lawsuit, she had argued that she meets the condition under Section 1(1)(a) of Part I of the Second Schedule to be a Malaysian citizen, namely that she was — immediately before Merdeka Day in 1957 — a citizen of the Federation of Malaya, based on the Federation of Malaya Agreement 1948. — Picture by Razak Ghazali

Beyond this citizenship case which ended on a happy note for her client, Larissa also highlighted the need to act against the government’s plans to make changes to the Federal Constitution — which citizenship lawyers and civil society have raised the alarm on — as those proposed amendments would further restrict Malaysian citizenship to genuine cases and may increase the number of persons who are stateless or without any nationality in Malaysia.

“I guess we can choose to win some battles, but the war isn’t won yet — we need to be very clear. With the proposed amendments on citizenship in the Federal Constitution, it will further restrict than enable.

“We must do something about this, if not, the stateless community will continue to grow without any recognition and protection. We need to remember, they are humans too that deserve a place in our land,” she said.

A common misconception is that stateless persons in Malaysia are only those such as refugees or those who were born outside of Malaysia.

But civil society group Development of Human Resources for Rural Areas (DHRRA) has identified at least thousands of cases of stateless persons with genuine links to Malaysia, such as those who were abandoned at birth in Malaysia; those who were born locally to Malaysian fathers before their marriage to foreign wives were registered; those who are born locally and have been adopted by Malaysian parents; those born here before Merdeka but were denied citizenship; and families with generations of stateless children born in Malaysia.