How to keep your New Year’s resolutions

We are creatures of habit. Between a third and half of our behaviour is habitual, according to research estimates. Unfortunately, our bad habits compromise our health, wealth and happiness.

On average, it takes 66 days to form a habit. But positive behavioural change is harder than self-help books would have us believe. Only 40 per cent of people can sustain their new year’s resolution after six months, while only 20 per cent of dieters maintain long-term weight loss.

Education does not effectively promote behaviour change. A review of 47 studies found that it’s relatively easy to change a person’s goals and intentions but it’s much harder to change how they behave. Strong habits are often activated unconsciously in response to social or environmental cues – for example, we go to the supermarket about 211 times a year, but most of our purchases are habitual.

With all this in mind, here are five ways to help you keep your new year’s resolutions – whether that’s taking better care of your body or your bank balance.

1. Prioritise your goals

Willpower is a finite resource. Resisting temptation drains our willpower, leaving us vulnerable to influences that reinforce our impulsive behaviours.

A common mistake is being overly ambitious with our new year resolutions. It’s best to prioritise goals and focus on one behaviour. The ideal approach is to make small, incremental changes that replace the habit with a behaviour that supplies a similar reward. Diets that are too rigid, for example, require a lot of willpower to follow.

2. Change your routines

Habits are embedded within routines. So disrupting routines can prompt us to adopt new habits. For example, major life events like changing jobs, moving house or having a baby all promote new habits since we are forced to adapt to new circumstances.

While routines can boost our productivity and add stability to our social lives they should be chosen with care. People who live alone have stronger routines so throwing a dice to randomise your decision making could help you disrupt your habits.

Our environment also affects our routines. For example, without giving it any thought, we eat popcorn at the cinema but not in a meeting room. Similarly, reducing the size of your storage containers and the plates you serve food on can help to tackle overeating.

3. Monitor your behaviour

“Vigilant monitoring” appears to be the most effective strategy for tackling strong habits. This is where people actively monitor their goals and regulate their behaviours in response to different situations. A meta-analysis of 100 studies found that self-monitoring was the best of 26 different tactics used to promote healthy eating and exercise activities.

Another meta-analysis of 94 studies informs us that “implementation intentions” are also highly effective. These personalised “if X then Y” rules can counter the automatic activation of habits. For example, if I feel like eating chocolate, I will drink a glass of water.

Implementation intentions with multiple options are very effective since they provide the flexibility to adapt to situations. For example, “if I feel like eating chocolate I will (a) drink a glass of water, (b) eat some fruit; or (c) go for a walk”.

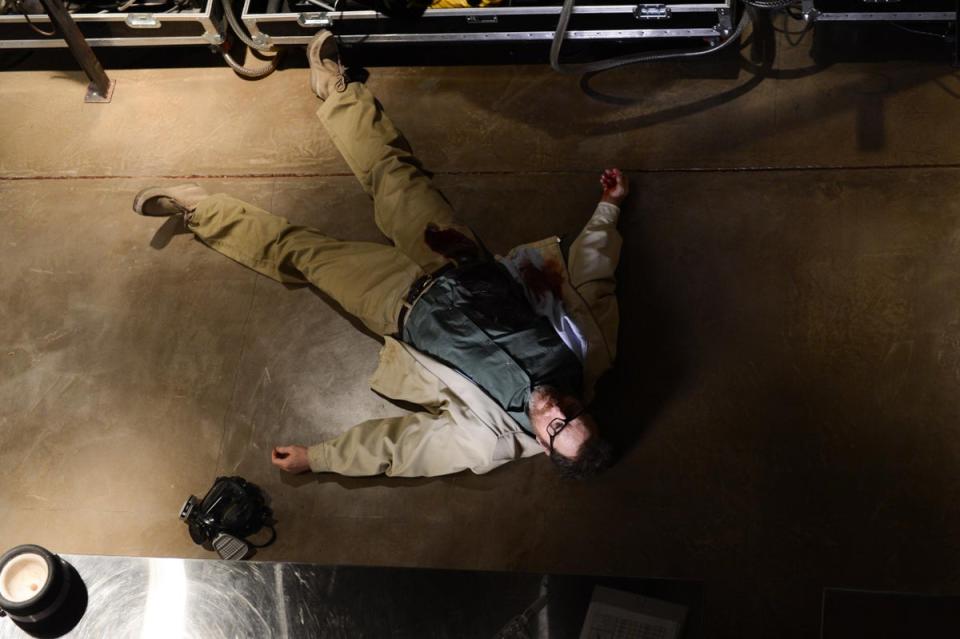

The 25 biggest cultural moments of the decade

But negatively framed implementation intentions (“when I feel like eating chocolate, I will not eat chocolate”) can be counterproductive since people have to suppress a thought (“don’t eat chocolate”). Ironically, trying to suppress a thought actually makes us more likely to think about it thereby increasing the risk of habits such as binge eating, smoking and drinking.

Distraction is another approach that can disrupt habits. Also effective is focusing on the positive aspects of the new habit and the negative aspects of the problem habit.

4. Imagine your future self

To make better decisions we need to overcome our tendency to prefer rewards now rather than later – psychologists call this our “present bias”. One way to fight this bias is to futureproof our decisions. Our future self tends to be virtuous and adopts long-term goals. In contrast, our present self often pursues short-term, situational goals. There are ways we can workaround this, though.

For example, setting up a direct debit into a savings account is effective because it’s a one-off decision. In contrast, eating decisions are problematic because of their high frequency. Often our food choices are compromised by circumstance or situational stresses. Planning ahead is therefore important because we regress to our old habits when put under pressure.

5. Set goals and deadlines

Setting self-imposed deadlines or goals helps us change our behaviour and form new habits. For example, say you are going to save a certain amount of money every month. Deadlines work particularly well when tied to self-imposed rewards and penalties for good behaviour.

Another way to increase motivation is to harness the power of peer pressure. Websites such as stickK allow you to broadcast your commitments online so that friends can follow your progress via the website or on social media (for example, “I will lose a stone in weight by May”). These are highly visible commitments and tie our colours to the mast. A financial forfeit for failure (preferably payable to a cause you oppose) can add extra motivation.

Brian Harman is a lecturer in marketing at De Montfort University and Janine Bosak is an associate professor in organisational psychology at Dublin City University. This article first appeared on The Conversation