No, the Warren-Sanders Feud Is Not About #MeToo

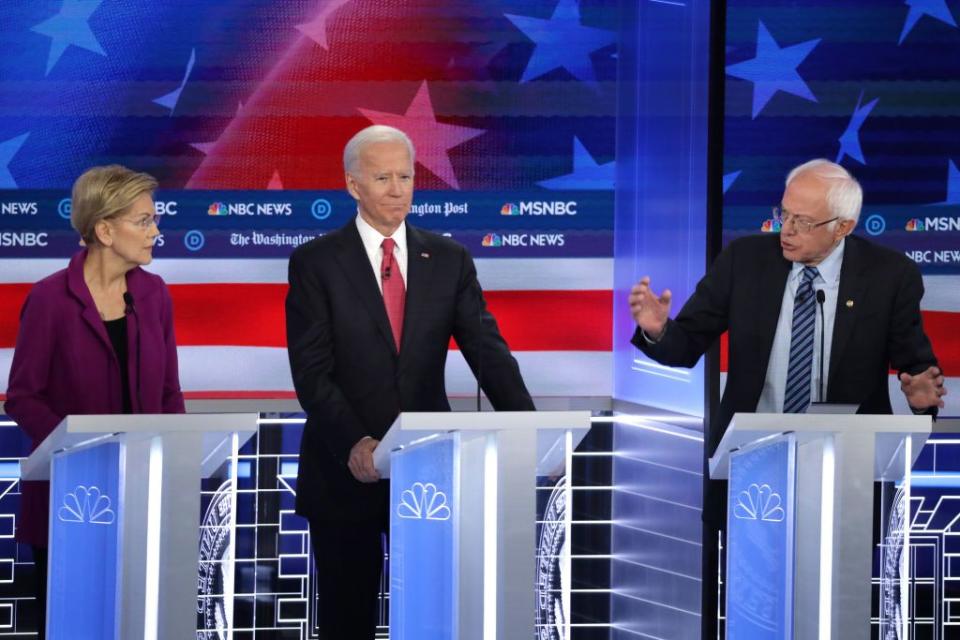

This week, the alleged “non-aggression pact” between Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders dramatically frayed. On Monday, CNN reported, citing anonymous sources, that during a 2018 sitdown, Sanders told Warren a woman couldn’t get elected president—a charge he vociferously denied. Warren doubled down, saying in a statement that when the topic came up, she said, “I thought a woman could win; he disagreed.” During Tuesday night’s debate, the moderators framed the incident as settled fact rather than in dispute, prompting another strong denial from Sanders and a tense interaction between the two Democratic presidential candidates afterward. Finally, late Wednesday, CNN published audio caught on the candidates’ hot mics of Warren rebuffing Sanders for calling her “a liar on national TV.”

Los Angeles Times columnist Virginia Heffernan lauded Warren’s handling of the exchange. Sanders’ attempt to shake his colleague’s hand, she argued, was coded as gendered violence: “We all know this stock male move: Come on, baby, give me a hug; we’re still friends.” She went on to assert that by contesting her campaign’s characterization of their 2018 meeting, “Sanders had gaslighted Warren”—a verb once used to mean a specific, insidious form of intimate partner violence.

CNN just posted the audio of the tense exchange last night.

Elizabeth Warren: "I think you called me a liar on national TV."

Bernie Sanders: "You know, let's not do it right now." pic.twitter.com/Ad0VN53Xux— philip lewis (@Phil_Lewis_) January 16, 2020

Other prominent women commentators also described the feud using the language typically reserved for gendered violence. “I just wrote a book laying out point by point how women are denied and demonized when they come forward with a sexual assault allegation, so watching Warren be disbelieved and blamed using the same tactics...is pretty surreal,” Guardian columnist Moira Donegan tweeted. GQ Magazine’s Julia Ioffe made a similar point: “Still thinking about the Warren-Bernie squabble and I have a question to people who have accused Warren of lying: Isn’t the lesson of #MeToo and the last few years that we believe women and don’t call them liars?”

The answer is no—of course believing women in every imaginable circumstance isn’t the lesson of the #MeToo movement. The phrase “believe women,” which became a rallying cry among survivors and their allies during #MeToo, isn’t a universally applicable demand but a highly contextualized one, meant to push back against the faulty idea that women frequently manufacture phony tales of trauma or weaponize them for personal gain. The phrase begs the listener to take these stories seriously, rather than starting from a place of skepticism.

Ascribing the appropriate moral heft to sexual assault surely must also mean refraining from using the same language to characterize a factual dispute in a national election. If “believe women” implores us to presume that women don’t deploy their stories for cynical reasons, it’s more than a little ironic to see pundits wielding the language of #MeToo in this way. The implication that a spat between two senators vying for the most powerful office on Earth is akin to sexual violence was not only craven and offensive but reflective of just how disingenuous arguments about sexism and Sanders’ campaign have become.

To be clear, I know how analogies work—they don’t necessarily seek to equate two things so much as the underlying dynamics, which is almost certainly what Heffernan, Donegan and Ioffe were getting at. But that’s only useful when the two things you’re comparing are similar enough to beg the same response, which isn’t the case here: denying a woman’s experience of sexual violence is callous and dehumanizing; disputing a political opponent’s factual characterization of a private conversation is mundane and all but inevitable in a presidential race.

Ultimately, the impulse to cast Sanders and his supporters as sexist—intended as a sharp contrast with the feminists behind Warren or Hillary Clinton before her—is based on an analysis of politics as a pop cultural product. In this telling, Warren is the beleaguered underdog heroine, taking on just another old white guy finger-wagging his way to the top. This obfuscates the structural power at work and the degree to which many people are drawn to Sanders’ candidacy for decidedly feminist reasons: In a starkly unequal country with a woefully inadequate welfare state, women disproportionately suffer the harms of poverty. Robust, universal programs guarantee basic dignity, and maximize women’s autonomy by shifting the financial burden of care from individual families to the broader public, all of whom have a stake in building healthy, happy, and stable communities. That feminist vision is impossible without class struggle and resource redistribution on an order that only Sanders calls for.

Reducing Warren and Sanders to characters in a movie about politics rather than power-wielding agents in their own right makes it easy to cast them as avatars for #MeToo. But in doing so, we risk falling back on some of the movement’s same limitations, like a primary focus on individual score-settling rather than building collective power from the bottom up to affect systemic change. #MeToo doesn’t urge us to uncritically accept a female presidential contender’s version of a news story; it urges us to take seriously women’s pain and fight for them to have control over their lives—and no one, least of all victims of sexual violence, is served by collapsing that moral distinction.

You Might Also Like