Wage growth slows sharply but continues to outstrip inflation

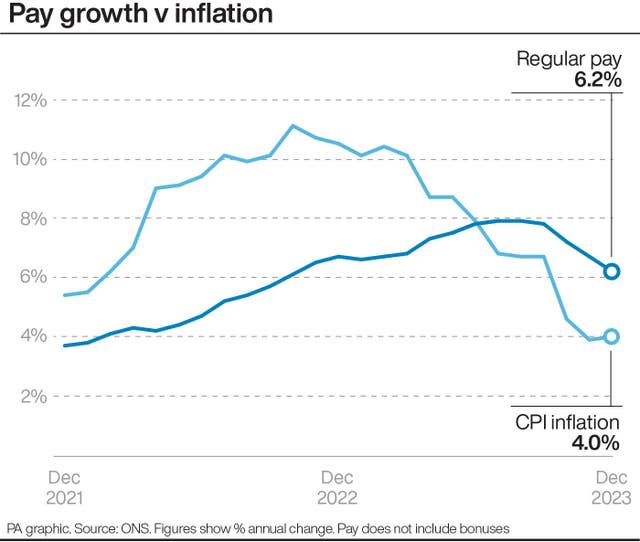

Wage growth has slowed to its lowest level for more than a year but is still outpacing inflation, according to official figures.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) said average regular pay growth, excluding bonuses, fell to 6.2% in the quarter to December, down from an upwardly revised 6.7% in the three months to November.

This was the slowest growth since the three months to October 2022.

But when taking Consumer Prices Index (CPI) inflation into account, real regular wages rose by 1.9% – a high since summer 2019, excluding the pandemic-skewed years.

This is thanks to inflation having fallen back sharply after hitting an eye-watering 41-year high of 11.1% seen in October 2022.

But the fall in wage growth was less than expected by most experts and in financial markets, with investors reining in their bets on interest rate cuts this year after the data.

Jake Finney, an economist at PwC UK, said: “The lingering concern for the Bank of England will be that the labour market has not cooled sufficiently to achieve a sustainable return to the 2% inflation target.”

The pound rose 0.3% to 1.27 US dollars and was also 0.3% higher at 1.18 euros on speculation that the figures have cut the chances for an early rate cut.

The Bank has been keeping a close eye on wage data in particular in its bid to bring high inflation back to target.

Figures suggested the jobs market as a whole remains largely resilient, with the unemployment rate falling to 3.8% in the final three months of 2023, down from 3.9% in the three months to November and the lowest level since November to January 2023.

But the ONS warned the unemployment rate should be “treated with additional caution” as it continues to overhaul its Labour Force Survey due to low response rates, with the full revamped version not due to be introduced until September.

There were signs elsewhere pointing to a cooling jobs market, as vacancies fell for the 19th straight month, down 26,000 to 932,000 in the three months to January, extending the record run of falls, although the decline was the smallest for a year-and-a-half.

Redundancies also jumped by 53% quarter on quarter to 116,000 in the last three months of 2023.

Added to this were figures showing the number of those classed as economically inactive in the jobs market rose to 9.3 million in the final quarter of last year, with another jump in those off work due to long-term sickness, to a record 2.8 million, up 8.4% year on year.

More timely data estimated that the number of workers on payrolls rose by 48,000 between December and January to 30.4 million, although this is subject to revision.

Liz McKeown, director of economic statistics at the ONS, said: “It is clear that growth in employment has slowed over the past year.

“Over the same period, the proportion of people neither working nor looking for work has risen, with historically high numbers of people saying they are long-term sick.”

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt insisted it was “good news” that real wages continue to rise, but admitted the “job isn’t done”.

He said: “It’s good news that real wages are on the up for the sixth month in a row and unemployment remains low, but the job isn’t done.

“Our tax cuts are part of a plan to get people back to work so we can grow the economy – but we must stick with it.”

The latest official inflation figures due on Wednesday may also add to rate-setter caution at the Bank, with most economists forecasting an increase for the second straight month, to 4.2% in January from 4% in December.

However, Samuel Tombs at Pantheon Macroeconomics warned that the official unemployment figures did not give an accurate picture of the UK’s jobs market.

He said: “The official unemployment rate gives a misleading impression of labour market tightness and we think the Monetary Policy Committee will place less weight than usual on it.

“The path to lower interest rates, therefore, remains clear, though it hangs in the balance whether the first cut will come before the end of the second quarter.”