Stone Age megastructure found submerged in the Baltic Sea wasn’t formed by nature, scientists say

Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

A megastructure found in the Baltic Sea may represent one of the oldest known hunting structures used in the Stone Age — and could change what’s known about how hunter-gatherers lived around 11,000 years ago.

Researchers and students from Kiel University in Germany first came across the surprising row of stones located about 69 feet (21 meters) underwater during a marine geophysical survey along the seafloor of the Bay of Mecklenburg, about 6 miles (9.7 kilometers) off the coast of Rerik, Germany.

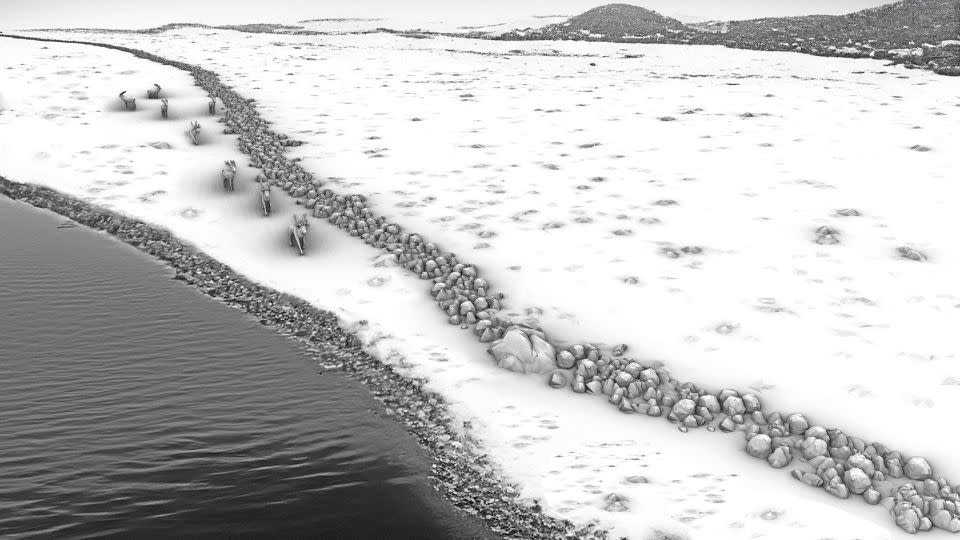

The discovery, made in the fall of 2021 while aboard the research vessel RV Alkor, revealed a wall made of 1,670 stones that stretched for more than half a mile (1 kilometer). The stones, which connected several large boulders, were almost perfectly aligned, making it seem unlikely that nature had shaped the structure.

After the researchers alerted the Mecklenburg-Vorpommern State Office for Culture and Monument Preservation to their find, an investigation began to determine what the structure might be and how it ended up at the bottom of the Baltic Sea. Diving teams and an autonomous underwater vehicle were used to study the site.

The team determined that the wall was likely built by Stone Age communities to hunt reindeer more than 10,000 years ago.

A study describing the structure was published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Our investigations indicate that a natural origin of the underwater stonewall as well as a construction in modern times, for instance in connection with submarine cable laying or stone harvesting are not very likely. The methodical arrangement of the many small stones that connect the large, non-moveable boulders, speaks against this,” said lead study author Dr. Jacob Geersen, senior scientist at the Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research in Germany, in a statement.

Turning back time

The wall was likely built more than 10,000 years ago along the shoreline of a lake or a bog, according to the study. Rocks were plentiful in the area at the time, left behind by glaciers that had moved across the landscape.

But studying and dating submerged structures is incredibly difficult, so the research team had to analyze how the region has evolved to determine the approximate age of the wall. They collected sediment samples, created a 3D model of the wall and virtually reconstructed the landscape where it was originally built.

Sea levels rose significantly after the end of the last ice age about 8,500 years ago, which would have led to the wall and large parts of the landscape being flooded, according to the study authors.

But things were different nearly 11,000 years ago.

“At this time, the entire population across northern Europe was likely below 5,000 people. One of their main food sources were herds of reindeer, which migrated seasonally through the sparsely vegetated post-glacial landscape,” said study coauthor Dr. Marcel Bradtmöller, research assistant in prehistory and early history at the University of Rostock in Germany, in a statement. “The wall was probably used to guide the reindeer into a bottleneck between the adjacent lakeshore and the wall, or even into the lake, where the Stone Age hunters could kill them more easily with their weapons.”

The hunter-gatherers used spears, bows and arrows to catch their prey, Bradtmöller said.

A secondary structure may have been used to create the bottleneck, but the research team hasn’t found any evidence of it yet, Geersen said. However, it’s likely that the hunters guided the reindeer into the lake because the animals were slow swimmers, he said.

And the hunter-gatherer community seemed to recognize that the deer would follow the path created by the wall, the researchers said.

“It seems that the animals are attracted by such linear structures and that they would rather follow the structure instead of trying to cross it, even if it is only 0.5 meters (1.6 feet) high,” Geersen said.

The discovery changes the way researchers think about highly mobile groups like hunter-gatherers, Bradtmöller said. Building a massive permanent structure like the wall implies that these regional groups may have been more location-focused and territorial than previously believed, he said.

Hunting sites around the world

The discovery marks the first Stone Age hunting structure in the Baltic Sea region. But other comparable prehistoric hunting structures have been found elsewhere around the globe, including the United States and Greenland, as well as Saudi Arabia and Jordan, where researchers have discovered traps known as “desert kites.”

Stonewalls and hunting blinds built for hunting caribou were previously found at the bottom of Lake Huron in Michigan and discovered at a depth of 98 feet (30 meters). The Lake Huron wall’s construction and location, which includes a lakeshore to one side, is most similar to the Baltic Sea wall’s, the study authors said.

Meanwhile, the scientists continue their investigation in the Baltic using sonar and sounding devices, as well as planning future dives to search for archaeological finds. Only by combining the expertise from those in fields like marine geology, geophysics and archaeology are such discoveries possible, Geersen said.

Understanding the location of lost structures and artifacts on the seafloor is key as demand for offshore areas increases due to tourism and fishing and the construction of pipelines and wind farms, he said. And other undiscovered treasures at the bottom of the Baltic could potentially shed more light on ancient hunter-gatherer communities.

“We have evidence for the existence of comparable stonewalls at other locations in the (Bay of Mecklenburg). These will be systematically investigated as well,” said study coauthor Dr. Jens Schneider von Deimling, researcher in the Marine Geophysics and Hydroacoustics group at Kiel University, in a statement.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com