The U.S. Is Now The World’s Top Exporter Of Liquefied Natural Gas

The United States sold more liquefied natural gas on the global market than any other country in 2023, surpassing yet another milestone in the nation’s transformation into a fossil fuel superpower.

Drillers across the U.S. broke records for production last year. By December, wells across the lower 48 states were generating nearly 106 billion cubic feet of gas per day.

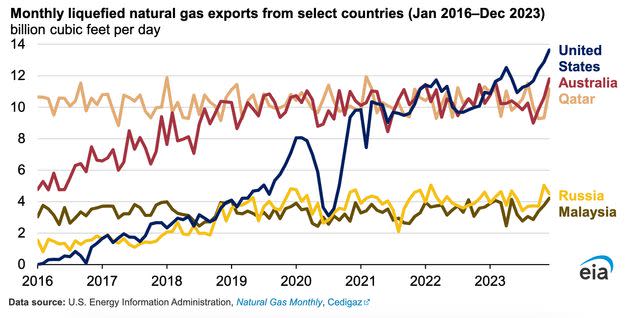

On average each day, almost 12 billion cubic feet were superchilled to nearly 300 degrees Fahrenheit below zero, shrinking the fuel to one-600th of its gaseous size, and shipped overseas to buyers in Europe and Asia, data published Monday by the federal Energy Information Administration shows.

Between 2020 and 2023, LNG sales from Australia and Qatar ― the world’s two other largest exporters ― ranged from about 10.1 billion cubic feet per day to 10.5 billion. In third place was Russia, which exported on average 4.2 billion cubic feet per day in 2023, followed by Malaysia, which averaged 3.5 billion.

U.S. exports saw massive growth last year, surging 12% compared to 2022.

The spike came after the Freeport LNG terminal in Texas ― which closed in June 2022 after a fire ― returned to full operations early last year and ramped up to full production by April.

The facility came back online right as European democracies were scrambling for alternatives to fuel that Russia had supplied via pipeline. Europe, including Turkey, accounted for 66% of all U.S. LNG exports, followed by Asia at 26% and Latin America and the Middle East with a combined 8%.

The Netherlands, France and the United Kingdom imported a combined 35% of all U.S. LNG exports last year as the continent expanded its infrastructure for receiving and storing more LNG.

The Dutch bolstered the size of the Gate LNG regasification terminal in the Rotterdam port, and commissioned two new floating units to store and turn superchilled liquid fuel back into its normal-temperature gaseous form. Germany commissioned three new offshore storage and regasification units.

In Asia, Japan and South Korea remained the largest buyers of U.S. LNG, but China and India increased imports compared to the previous year. The Philippines and Vietnam began importing U.S. LNG last year.

The U.S. used to import much of its fuel from abroad, leaving the country sensitive to supply cuts from the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, the oil-producing cartel that engineered an energy crisis in North America and Europe in the early 1970s as punishment for Western governments’ support of Israel.

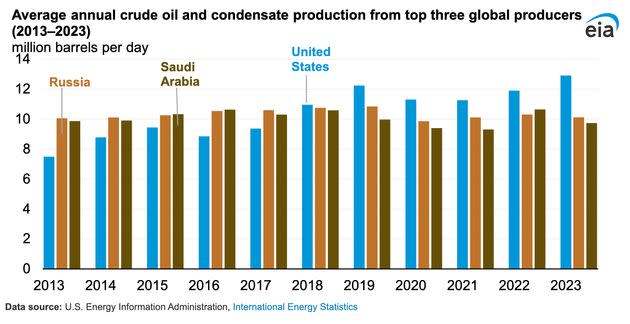

Now, attempts by OPEC+ ― the expanded club that now includes Russia ― to cut supplies do little to drive up oil prices, in part because the U.S. currently accounts for such a large share of global production.

That’s thanks in large part to horizontal drilling technology, the breakthrough approach widely known as “fracking,” which made it possible to tap the vast reserves in previously unreachable rocks beneath North Dakota, Pennsylvania and West Texas.

Combined with cheap loans from Wall Street, the fracking revolution unleashed an oil- and gas-drilling boom so big, U.S. politicians are still struggling to find the right ways to talk about it. Republicans accused Democrats of squelching the American drilling industry with climate regulations, with GOP lawmakers blaming President Joe Biden’s pursuit of more zero-carbon energy for any spike in fuel prices. Environmentalists, meanwhile, are split between lambasting Biden for the fossil fuel bonanza and praising the signature climate laws he passed to fund a massive buildout of electric car chargers, solar factories and nuclear plants.

Installations of wind turbines, solar panels and batteries hit a record high last year. But so, too, did oil production. The U.S. now “produces more crude than any country, ever,” the EIA announced last month. U.S. exports of crude are soaring.

The cost of driving may be much lower in the U.S. than in other rich countries, which is in part a symptom of how politically difficult it is to raise taxes on fuel when much of the continent-wide nation lacks basic public transit options. Yet even with record domestic drilling, all the fuel going abroad did little to insulate Americans from price swings on the global market.

Americans in 2023 consumed less natural gas for heating and cooking than at any point in the past five years, federal data shows. But the country used more of it than ever to generate electricity, and demand for power is forecast to grow this year.

So, too, is utility debt. Ratepayers’ combined arrears to energy companies swelled to nearly $21 billion last year, a record. And average residential electricity prices last month hit their highest levels in three decades.