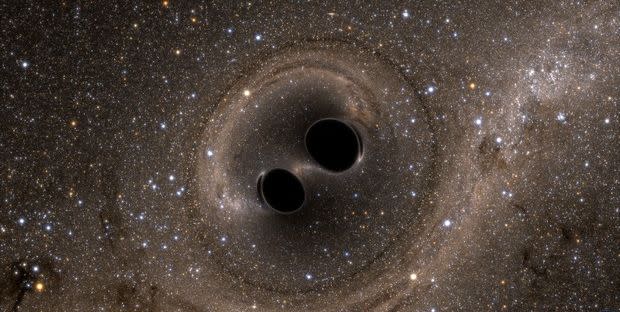

Two Black Holes Are Merging at the Center of a Distant Galaxy

Astronomers have been tracking interstellar flares, which they believe are coming from a binary black hole system in a faraway galaxy.

They expect to spot another flare in April, and are training their instruments in that direction, Scientific American reports.

Us Earthlings shouldn't hold our breath for a display of celestial fireworks, though. The suspected merger likely won't happen within the next 100,000 years.

Strange things are happening in dark corners of the universe.

Astronomers have been tracking bright jets of high-energy particles that periodically wriggle their way through the universe and into sensors here on Earth. The Kepler space telescope picked up the latest such flare in 2011. Ever since then, scientists have been stumped.

Years ago, scientists proposed that the flares could be caused by a strange, amorphous celestial object—two supermassive black holes, trapped in two different galaxies, circling each other. They playfully named the cosmic object “Spikey.”

As supermassive black holes scoot closer and closer to each other, they begin to gobble up bits of dust and gas and belch particles out into space. These high-energy flares, which can be picked up from telescopes orbiting Earth, suggest the supermassive black holes really are on a collision course. But astronomers aren’t holding their breath. They expect the meeting won’t happen for another 100,000 years—an astronomical blink of the eye.

Scientists clued in on the interstellar dustup thanks to a theory proposed in 2017 by two Harvard astrophysicists. They suggested that such a cosmic meeting might be visible thanks to gravitational lensing, when light traveling toward a hypothetical merger bends and warps around the feature, sending out a bright jet of high-energy particles. “It’s a very distinctive signature,” Harvard's Rosanne Di Stefano told Scientific American, which first reported on the story. Unfortunately, the flares are largely unpredictable.

Last October, a team of astronomers led by Daniel D'Orazio, Di Stefano's colleague, reported on a flare they had found within Kepler data collected in 2011. They've predicted that another flare will crop this coming April, and have scheduled time on NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory to look for it. If the observatory catches sight of Spikey’s flare, which could last up to 10 days, astronomers could have a solid blueprint for how to observe other binary supermassive black hole systems.

“If it holds up and is, in fact, a binary, I think it will give us a case of what to look for if we’re trying to find cases of close binaries not yet merged,” astrophysicist Scott Hughes of MIT told SciAm.

As these speeding galaxies race toward each other, the black holes at their respective centers may get into a bit of a jam. The gravity pulling them together isn’t strong enough to overcome the centrifugal force exerted by each black hole, SciAm reports. If they aren’t able to get over the hump, the two black holes may stay locked in this dance, circling other in perpetuity.

April’s flare is still up in the air. In our complex and mysterious universe, nothing is guaranteed.

You Might Also Like