Terrifying dragons have long been a part of many religions, and there is a reason for their appeal

HBO’s prequel to “Game of Thrones,” “House of the Dragon” brought renewed attention to the ferocious dragon. Two-legged or four, fire-breathing or shape-shifting, scaled or feathered, dragons fascinate people across the world with their legendary power. This shouldn’t be surprising.

Long before “Harry Potter,” “Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings” and other modern interpretations increased the dragon’s notoriety in the 21st century, artifacts from ancient civilizations indicated their importance in many religions across the world.

As a scholar of monsters, I’ve found dragons to be a nearly universal symbol for many civilizations. Scientists have tried to come up with explanations for the myth of dragons, but their enduring existence is testimony to their narrative power and mystery.

Ancient dragons, ancient stories

Religions and cultures across the globe are rife with dragon lore. In fact, across the vast majority of religions, there is mythic trope some scholars call Chaoskampf, a German word that translates as struggle against chaos. This term, used by mythologists, refers to a pervasive motif involving a heroic character who slays a primordial chaos “monster,” often with serpentine or dragonlike characteristics and a massive size that dwarfs humans.

One ancient example is found in the “Enūma Eliš,” a Babylonian creation text from around 2,000 to 1,000 years B.C..

In the text, Tiamat, the female primordial deity of salt water and matriarch of the gods, births 11 kinds of monsters, including the dragon. While Tiamat herself is never described as a “dragon,” some of her children, or “monsters,” include several different kinds of dragons with explicit references to her dragon children. Iconography later evolved so that her appearance began to take on serpentine features, linking her image to another famous clawed mythological predator, the dragon.

Dragons in Chinese and other cultures

The presence of the dragon in China, where it is called Long is also ancient and integral to various cultural, spiritual and social traditions.

Dragons are members of the Chinese zodiac, one of the sacred guardian creatures that make up the Four Benevolent Animals and provide justification for imperial dynasties. Different kinds of these aquatic, intelligent, semidivine beings form a hierarchy in ancient Chinese cosmology and appear in creation myths of various indigenous traditions.

When Jesuit missionaries reintroduced Christianity in China in the 16th century, the dragon’s existence was not contested. Instead, they became associated with a more Westernized explanation – the Devil.

Today, dragons are celebrated and revered in Buddhist, Taoist and Confucianism traditions as symbols of strength and enlightenment.

Dragons also appear in Anatolian religions, Sumerian myths, Germanic sagas, Shinto beliefs and in Abrahamic scriptures. The creature’s repeated and important presence across global religions and cultures raises an interesting question: Why did dragons appear at all?

Symbolic power

A long-proposed theory is that there are natural explanations for dragons. That’s not to say the beasts of myth existed in real life but rather that fossils, living animals and geological features existing in the natural world inspired their creation.

Pulitzer Prize-winning author and scientist Carl Sagan wrote a book on the subject, arguing that dragons evolved from a human need to merge science with myth, the rational with the irrational, as part of an evolutionary response to real predators. His thoughts are an expansion of proposed ideas beginning in the 19th century or earlier as newly discovered fossils were linked to representations of dragons across the globe.

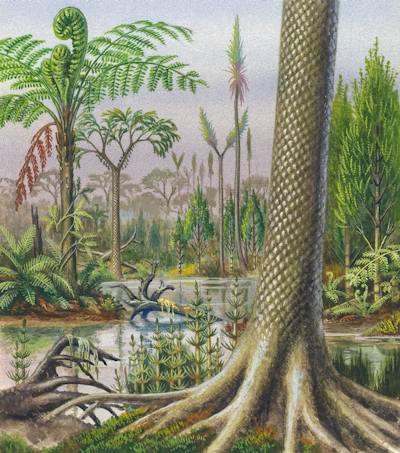

Full or partial remains of numerous extinct species may explain the physical attributes of dragons. In 2020, two scholars, DorothyBelle Poli and Lisa Stoneman, even proposed that the fossilized remains of Lepidodendron, a plant with a scalelike resemblance, may be behind the global presence of dragons.

Human encounters with flying lizards, oarfish, crocodiles, Saharan horned vipers, large snakes and certain species of lizards and birds have also been proposed as possible explanations for dragon lore, given their physical resemblance to different dragons.

Scholars have also cited natural geologic processes as explanations for dragon lore – particularly when they are associated with natural disasters. Fire-breathing dragons, for instance, might be an explanation for mysterious fires that observers attempted to rationalize as a dragon’s flame. Natural gas vents, methane produced from decaying matter and other sources of underground gas deposits can produce a blaze if accidentally lit. Before the mechanics of combustion were understood fully, such events were deemed indicators of a dragon’s presence, providing a cause for the seemingly implausible.

Eternal dragons

One enduring reason dragons continue to appear in our world could be because they represent the power of nature. Stories about people taming dragons can be seen as stories about the ability of humans to dominate forces that cannot always be controlled.

To gain control over a dragon underscores the problematic idea that humans are superior to all other animals in nature. Dragons challenge the concept of human biological supremacy, raising questions about what it means if humans were forced to reposition themselves as lesser members of the food chain.

More importantly, I believe, the beauty, terror and power of the dragon evokes mystery and suggests that not all phenomena are easily explained or understood.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Emily Zarka, Arizona State University

Read more:

Emily Zarka ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.