Talbot Bashall, public servant who gave a new life to thousands of Vietnamese boat people – obituary

Talbot Bashall, who has died aged 94, was a public official who in the 1970s helped thousands of Vietnamese boat people find safe haven, at first in Hong Kong, where he ran the Refugee Control Centre, and then throughout the world.

In the 20 years following the end of the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, 800,000 ethnic Chinese people fled the country by sea, although many died due to storms, pirates and overcrowded boats. They headed for Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand, where they were housed in camps before being dispatched to settle permanently in other countries.

In Hong Kong, Bashall led the Herculean task of processing them all and seeing them off safely. It was, he said, “a challenging and demanding job – but a deeply satisfying one”.

Talbot Henry Bashall was born in the village of Ripley in Surrey on July 19 1926, one of four children. He left school at 17 and joined the RAF, volunteering for aircrew duty, but the following year, with fewer crew needed as the war approached its endgame, he was transferred to the Army, undertaking officer training at Mons Barracks in Aldershot, and Sandhurst.

In 1946, by now a lieutenant, he was sent to Venice to guard Germans facing trial for war crimes, most notably Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, who had led the defence of Italy before ending the war commanding German forces on the Western Front.

“He shook my hand and said he was very pleased to meet me,” Bashall recalled of their first meeting. “There was no field-marshal kind of arrogance at all.”

Earlier in the war Kesselring had led the Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain, a fact not lost on Bashall. “I used to watch the German planes flying over and sometimes heard the whistle of bombs as they fell,” he recalled in an interview with the South China Morning Post in 2010. “I could never have imagined meeting one of the planners of those raids, let alone befriending one.”

It was Bashall’s job to escort the German along the Grand Canal to trial each day: “My God, I’m living history,” he recalled saying to himself one day. They would have lunch together, discussing battle tactics, and then in the evening “we’d talk for an hour or two about everything under the sun.”

The pair established such a strong rapport that when Bashall accidentally left a bottle of sleeping pills in Kesselring’s room the Field Marshal returned it immediately, telling his guard: “I understand that if anything happens to me, you’ll be responsible, so you’ve no need to worry.”

After Kesselring’s initial death sentence was passed, Bashall told him he was sorry, and when they parted, the Field Marshal presented him with a book Fighting on Roman Soil, by the German war artist, Wilhelm Wessel. It was inscribed “To Lieutenant Talbot Henry Bashall with my best wishes for the future and with many thanks for the comrade-like and friendly attitude towards me.”

Kesselring’s death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment (a measure many on the winning side supported, including Winston Churchill); he was released in 1952 suffering from throat cancer, but lived until 1960.

Bashall’s battalion, part of the First Armoured Division, 61st Lorried Infantry Brigade, was sent as a peacekeeping force to Palestine, where he witnessed boatloads of Jewish immigrants arriving, and the move towards a nascent Israel. That was his last posting, and he left the Army, having decided on a career in forestry.

He met and married Cynthia, a former Wren, who worked for the Royal Horticultural Society at Wisley. They had two children, and with money tight, Bashall applied for a more lucrative job in the Hong Kong prison service.

He attended a prison training school in Yorkshire, and arrived in Hong Kong in 1953 as the colony’s first expatriate prison officer. He worked at the maximum-security Stanley Prison for four years then took on the training of new guards.

He went on to work for the hawker control force, which regulated street-sellers, a job he did not enjoy. When it was disbanded in 1979, he recalled, “It was like the end of a sentence of 10 years’ penal servitude.”

He was by then still only 52, too young to retire, and he was appointed head of the newly established Refugee Control Centre – just in time to deal with the exodus from Vietnam, which had started as a trickle in 1975 but had since become a flood.

One of the ships to approach Hong Kong was the Skyluck, which was carrying 2,600 asylum-seekers. In February 1979 it was refused permission to dock and, with its engines disabled by the Hong Kong Marine Police, remained anchored in the West Lamma Channel.

Eventually, the desperate refugees, believing they had been abandoned by the world, cut the anchor chains. On June 29 1979 Bashall recorded in his diary: “In office at 07.45 and then at 09.30 it all started: Skyluck cut her anchor chain and drifting. The proverbial hit the fan and we were off.”

The Skyluck was just one of many boats arriving, and Bashall and his team struggled to process, feed and house all the refugees. On May 11 1979 he wrote in his diary: “The storm hit me as the magnitude of the influx became evident. Boats queuing up to get in choking up the approaches. Really a horrific situation.”

On June 30, the day after the Skyluck had foundered, the South China Morning Post reported that there were 58,667 refugees in Hong Kong camps, while in the region as a whole there were around 350,000.

While other countries began to turn them away, Bashall held firm. “We didn’t turn a single boat away during my posting,” he recalled, “and I was there for three and a half years, day in and day out. I am very, very proud of that fact.”

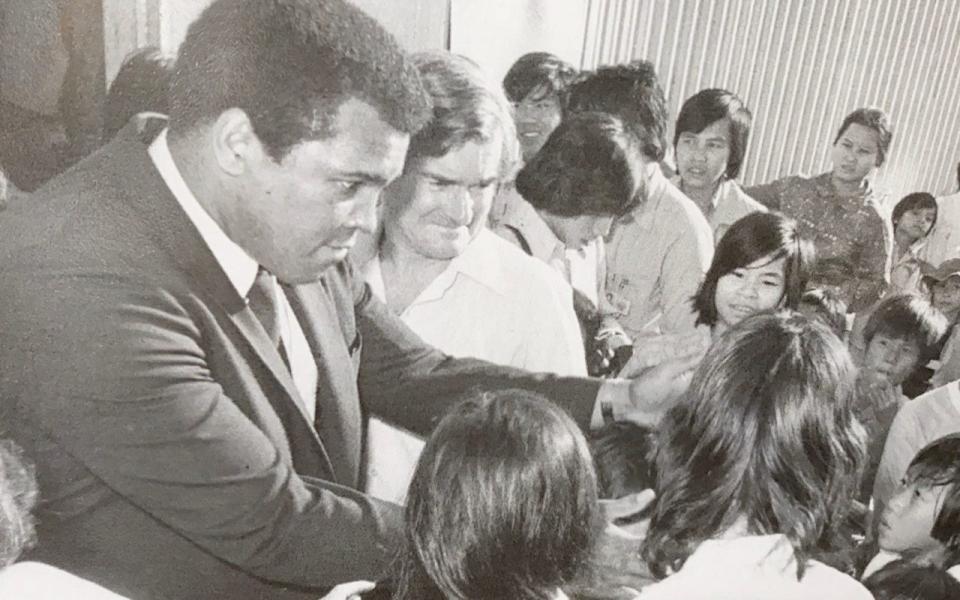

A notable visitor to the camp was Muhammad Ali. Bashall, who showed him around, recalled that the refugees were enthralled by the boxer’s charisma.

Hong Kong did not finally close its last camp until 2000, but by then Bashall was long gone. In 1982 he left Hong Kong and retired to Perth in Australia, where he remained for the rest of his life. He wrote and gave talks about refugees alongside Carina Hoang, who he had helped as a young girl when she arrived from Vietnam. He was awarded the Silver Jubilee Medal and the Imperial Service Order.

Talbot Bashall’s wife Cynthia died in 2011, and he is survived by their daughter and son.

Talbot Bashall, born July 19 1926, died September 6 2020