What the Supreme Court Will Do With the NYT AI Case and What It Means for Media and Entertainment

If Big Tech and the AI industry felt they received the creative community’s collective stink eye in 2023, then they have no idea what will hit them in 2024. This year promises an ongoing onslaught of AI-related copyright infringement cases filed by the largest and most influential media and entertainment companies on the planet.

Case in point: The New York Times’ multi-dimensional case against Microsoft and OpenAI for both unlawful scraping of its journalistic content and infringing competition, which it filed just before the ball dropped in Times Square. That suit, together with others before and after it, will define the basic rules of copyright that will transform the media and entertainment business. They will define what can and cannot be done without consent and compensation both on the AI “input” and “output” sides of the equation.

Most people with whom I’ve spoken believe that the U.S. Supreme Court will ultimately decide the issue, and many believe the Justices will rule in favor of Big Tech and find “fair use” consistent with what is commonly referred to as the landmark “Google Books” case. But that case wasn’t decided by the Supreme Court. It was decided by the 2ndCircuit Court of Appeals in 2015, which ruled in Google’s favor against authors who had claimed mass infringement by Google’s “Book Search Project” — in which the behemoth vacuumed the entirety of text from the libraries of the world to make it all searchable. The Supreme Court refused to review the 2nd Circuit’s decision when it denied certiorari. That means that “Google Books” is not precedent it must follow.

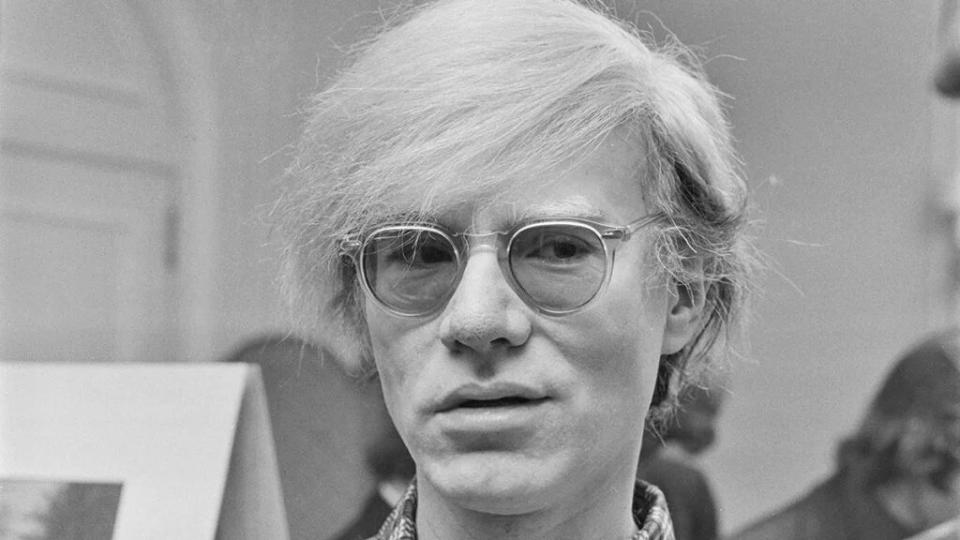

Today’s Supreme Court is also fundamentally different today than it was in 2015. Three new Justices, all Trump appointees, have joined since then, and the Court has also directly ruled on pivotal copyright cases since that time. Two particularly relevant cases are Google v. Oracle decided in 2021 (yes, Google again in the infringer hot seat) and last year’s surprising Andy Warhol-Prince ruling.

In the first, in a 6-2 decision (there was an open seat at the time), the Justices ruled that Google’s direct copying of 11,500 lines of Oracle software code — copying Google had conceded — was a fair use. In the Warhol case, the Court went the other way in a 7-2 decision, rejecting Warhol’s fair use defense based on a new kind of economic “harm to creator” element it defined for the first time. Interestingly, two of the most liberal Justices — Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan — split on that decision with strongly worded rebukes of each other’s reasoning.

So what do these rulings portend for how the Justices will decide between infringement and fair use in the realm of generative AI when there is mass non-consensual “training” on the input side and frequently direct adverse market impact to creators on the output side? Well, let’s first look to the lower federal courts and where they seem to be heading.

So far, as I’ve written previously, the few federal judges who have ruled on those issues have concluded “fair use” when confronted with Big Tech’s mass scraping of copyrighted works. Those judges — including in the high-profile Sarah Silverman case — rationalized that the eventual AI outputs bore no direct relation to any specific creative work that had been hoovered into the AI’s training vortex. In other words, Silverman and others could prove no adverse market impact. At first blush, that reaction seems to make sense and is consistent with “Google Books,” a case which the Silverman court cited.

But let’s step back a bit, as the The New York Times case presents a master class in pleading and litigation. Unlike other media-related AI infringement cases before it, The New York Times goes further and makes the case for direct market harm, seeking “billions of dollars in statutory and actual damages.” The Times contends that Big Tech’s AI-focused efforts serve no “Google Books”-like service to its journalists and brand.

In “Google Books,” the 2nd Circuit found fair use because Google ultimately displayed only snippets of the scraped books rather than the whole enchilada. So, the 2nd Circuit reasoned, Google’s “revelations do not provide a significant market substitute for the protected aspects of the originals.” Instead, the Court concluded that Google directly benefited authors by shining more light on their writings.

The Times points out that Big Tech’s mass copying in the AI context is entirely different. Here, Microsoft and its rambunctious nephew OpenAI are directly copying tens of thousands of its articles precisely to offer a market substitute and compete with it. In essence, Big Tech is looking to build trillions of dollars of future value, once again, on the backs of the creative community by using its AI algorithms to do what it could not do itself — create the content that fuels its synthetic output-spitting machine.

The Times has a point here — a massive one — and the U.S. Supreme Court may be quite open to hearing it. First, as noted above, the Court never ruled on the specific “Google Books” case, so it is not a precedent it must follow. Second, its 2021 Google vs. Oracle case dealt with purported infringement of computer code, not creative works, a distinction that the Court itself noted. And finally, in Warhol, the freshest ruling of the bunch, the Court defined a new “economic harm to creator” test when rejecting Warhol’s fair-use defense. Seven of the nine Justices were on board with that ruling, including both the most conservative and most liberal of Justices, in a rare moment of bench-wide solidarity.

In The New York Times case and others before it (including Getty Images, which also focuses on AI market substitution), it’s hard to challenge the contention that real economic harm results directly from the non-consensual and non-compensated direct wholesale copying of copyrighted works. Subjective creative works are entirely different than objective computer code.

Further, AI outputs ultimately can — and in many cases are intended to — serve as direct market substitutes for the works that have been scraped, even if those outputs don’t bear any direct relation to the works at hand. Make no mistake — Big Tech ultimately wants us to use its AI as our source of news, instead of The Times. Unlike in “Google Books,” that shines no light on The Times that draws us in. Instead, it casts a glare that pushes us away.

For all these reasons, I strongly suspect that the Supreme Court ultimately will be sympathetic to The Times and the creative community in general and rely most on its recent Andy Warhol ruling.

Big Tech AI faces a significant crisis due to this very real potential outcome, and its best bet is to stop The Times’ and other litigation dead in their tracks. Microsoft and OpenAI should settle with The Times and proactively work with creators to define both compensation schemes and some real guardrails that benefit them so that Big Tech can deliver on the promise of its AI in the world of media and entertainment, fairly. Such negotiations are, in fact, happening now, even as Big Tech litigates onward.

One way or another, creators and their works must be respected, protected and compensated. Perhaps that compensation will be in the form of a YouTube-like Content ID system. Google has already developed something called SynthID that identifies creative works scraped by its AI. Perhaps that compensation will come from Spotify-like royalties to artists. Perhaps it will be akin to Adobe Firefly’s scheme that pays participating “opt in” artists based on the amount of their visual works included in the AI’s training data set.

But there should be no free lunch. Human creativity must be respected, so long as we humans still rule the day.

For those of you interested in learning more, visit Peter’s firm Creative Media at creativemedia.biz and follow him on Threads @pcsathy.

The post What the Supreme Court Will Do With the NYT AI Case and What It Means for Media and Entertainment appeared first on TheWrap.