He Spent His Career Helping Films Like 'Avatar' Come to Life. Now He's Using His Expertise to Fight the Coronavirus.

A little after 8 p.m. on Sunday, March 22, Gary Martinez received a flurry of texts from one of his co-workers at Technoprops, a division of Industrial Light & Magic, the visual effects and animation studio founded by George Lucas in 1975 and owned by Lucasfilm.

Two engineers in northern Italy were 3D-printing ventilator valves for local hospitals, part of a grassroots effort to address the shortage of medical supplies to fight the novel coronavirus.

If engineers could do this in Italy, Martinez’s colleague wanted to know, couldn’t someone in film production, someone used to working to the standards of cinema’s most exacting directors, do it too?

And maybe even better?

Martinez, a lean fifty-five-year-old former Navy sonar technician and the mechanical supervisor at Technoprops, was already at work devising his own plan. He had spent twenty-five years helping bring to life some of Hollywood’s biggest films (Avatar, Star Wars: The Force Awakens, and Avengers: Endgame, among many others). Now that the pandemic had halted production throughout the industry, he found himself unable to sit at home in the San Fernando Valley without a complex technical challenge to focus on.

It was that obsession with solving problems, coupled with a fanatical attention to detail, that made Martinez stand out in the high-pressure, high-stakes perpetual-motion machine of the movie business.

“Gary is someone you only have to ask something once,” says Paul Fleschner, the team producer at ILM who texted Martinez. “And he’ll come back with three solutions, all better than you anticipated.” (Fleschner and I went to college together, which is how I became aware of this effort.)

It did not take Martinez long to figure out that making valves wouldn’t work. Not only did different ventilator models require different valves, but the highly contagious nature of the virus required that each valve be discarded after use.

With Governor Gavin Newsom’s stay-at-home order in place as of March 19, Martinez had no access to the highest-end machinery in Technoprops’ arsenal. Most important, though, he wasn’t comfortable printing pieces of equipment that could endanger patients if they failed.

He pored over Internet healthcare forums and academic papers hoping to land on a better option. The one he found seemed oddly perfect for a man immersed in the world of Storm Troopers and superheroes: Martinez would throw all his design expertise into making reusable, easily disinfected, clear plastic face shields.

He was by no means the first to do this.

Engineers, students, and tech-savvy hobbyists around the world had been designing and printing their own shields for several weeks and posting the results on social media. Some were churning them out by the thousands.

Martinez was moved by the creativity and rapid response of those who had stepped up to help, but he noticed that many of their prototypes had at least one design flaw: The plastic sheet that wrapped around the wearer’s face was often made of an 8.5-by-11-inch piece of acetate—similar to the transparencies used for overhead projectors—which did not extend all the way to the ear. That left a large gap around which respiratory droplets expelled from a patient with COVID-19 could travel and land on the wearer’s skin.

Acetate is also relatively flimsy and occasionally cloudy, even when molded into a rigid shape.

On top of that, some of the headbands on the shields did not form a complete seal on the forehead, leaving another possible entry point for the virus.

In recent years, thinking about headgear had become a big part of Martinez’s job—he supervised the fitting and alignment of the helmet-mounted facial-capture cameras that James Cameron used in Avatar.

But he had other reasons to think about it, too.

He was on the U.S.S. David R. Ray in the Persian Gulf when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in August 1990, and he was issued a gas mask in case of a chemical-weapons attack. Had he needed that mask, his life could have depended on the strength of his gear.

This pandemic was a much different kind of war, but Martinez didn’t want anyone wearing his shield on the frontlines to be afraid of it failing them. He wanted it to be made with durable, high-quality materials to maximize safety and comfort.

“I wanted to know that the shield worked in my hands, on my head,” he says. “I wanted to make a good product. Everyone is obsessed with the speed at which you can print these things out, but that doesn’t matter if you can’t keep the user safe by meeting the requirements.”

Martinez, who grew up in Los Angeles, has been making things all his life. When he was twelve, he fashioned his first light-saber out of a flashlight after seeing the original Star Wars at Mann's Chinese Theatre. The film “woke me out of just doing nothing to doing something,” he says. He began making his own costumes, models, and gadgets. In 1995, he quit his post-Navy job installing alarm systems, pulled out the phone book, and went to every special-effects studio he could find until one of them gave him work.

Now Martinez launched himself into sketching shield prototypes and sourcing materials from the few distributors still taking orders. He consulted his nephew, a radiology tech at Los Robles hospital in Thousand Oaks, and several other medical professionals in his family for feedback on the design.

Using his network of industry connections, Fleschner rounded up $6,000 to cover the cost of ten Creality CR-10 printers, several rolls of polylactic-acid filament, some quarter-inch polyethylene closed-cell foam, and a few spools of elastic from a local fabric store. Martinez had them all shipped to his house, where the packages began piling up in his driveway, and shuttled them to a then-empty workshop in Van Nuys.

On Tuesday morning, Fleschner texted again, this time a link to a story a friend had sent him about a Taiwanese doctor who had invented a clear plastic box with two arm holes that could be placed over a patient’s head during intubation. This would reduce the spray of respiratory fluid that occurred when the patient gagged or coughed as the tube was inserted. The friend, who worked as a respiratory therapist at a hospital in Indiana, hoped that Fleschner could help him find something similar.

I can make that, Martinez thought. But I can make it lighter and better and easier to manufacture.

Within three days of the initial exchange, Martinez was running all ten printers on the concrete floor of the workshop in Van Nuys, where he worked at his desk alone under a shelf of Star Wars and Indiana Jones memorabilia. He arrived early and stayed late, watching over the CR-10s as they whirred and hummed during their three-hour runs.

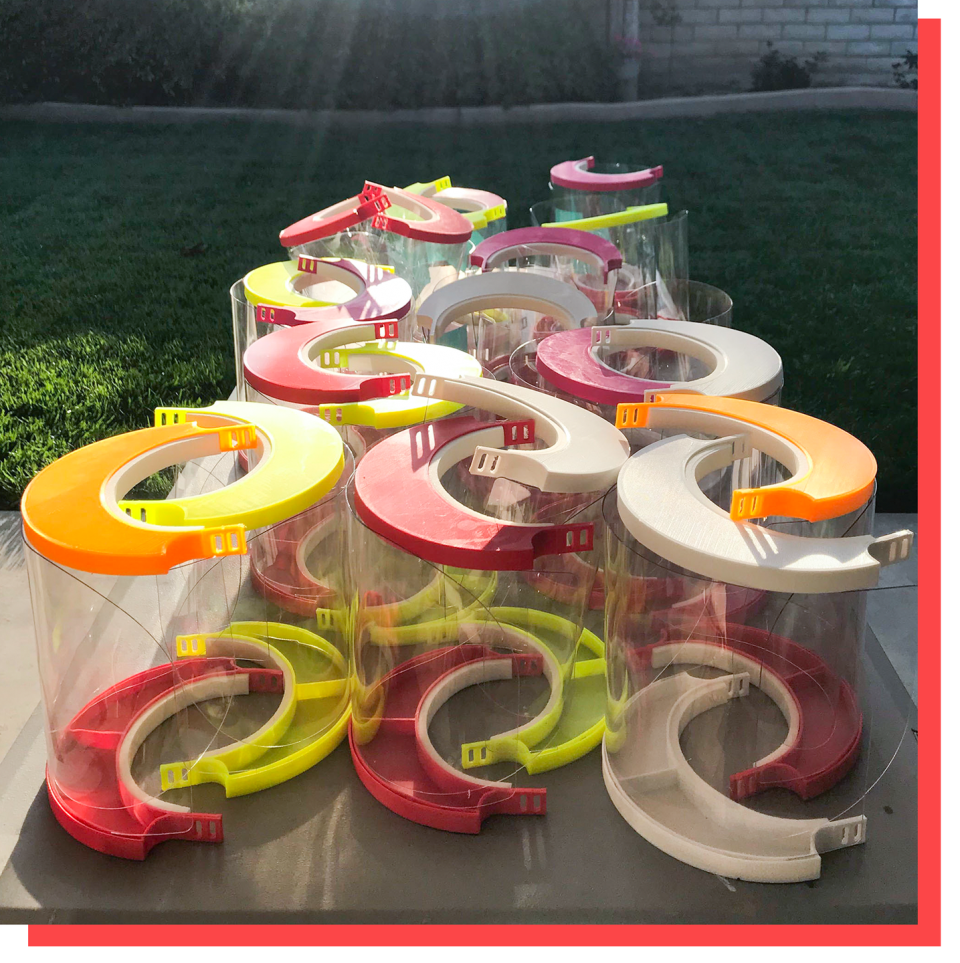

While the printers made the shield headbands, Martinez cut 16-by-10 sheets of thicker clear plastic by hand and fed them into a Glowforge laser cutter, ultimately heat-bending each one into the proper curve. He wasn’t able to move as quickly as he'd wanted, but he could make forty shields in one twelve-hour shift.

When Martinez returned home and collapsed into bed each night, his brain would not stop working. He dreamed of ways to make his designs better. His brain would simply not stop working on them. The aerosol box, he realized, could be curved on one side to make it more comfortable for a healthcare worker to lean over and easier for the patient to see out of.

Every time he thought about the patient underneath the plastic—what that person must be going through during an intubation—the gravity of what he was trying to do hit him “right in the gut.”

The question was: Would any hospitals actually want these things? If so, how would Martinez deliver them?

And how could they step up production if they needed to?

On Friday, March 27, the first shield prototype went to Martinez’s nephew at Los Robles, who immediately began using it and spreading the word among his coworkers. The second went to Fleschner’s friend at Union Health in Indiana, along with a prototype for the aerosol box.

The box was used for the intubation of a COVID-19 patient almost as soon as it was unpacked, and staff at Union placed orders for ten more, along with 100 more shields.

“The number-one thing I am worried about is my staff members getting exposed,” says Jimmy McKanna, the respiratory-therapy manager at Union Health. “The shields we were using before were mass-produced and pretty flimsy. We’ve never been at the point where we had to wear shields all day long, so the comfort and sturdiness of these is really important. They will last much longer.”

Like Martinez, McKanna has been dreaming a lot, too—though his nightmares are in which his name is on the patient board, and he can only pray that his caregivers have everything they need.

Two days later, a venture capitalist in Menlo Park contacted Fleschner on behalf of her sister, an anesthesiologist at Kaiser Permanente in Santa Clara. She wanted shields for every member of her anesthesia team—roughly sixty people. (Martinez and Fleschner ship the equipment to individuals, who then distribute it to coworkers at their discretion.)

The orders are flowing in steadily, with another hundred shields currently slated for distribution at several hospitals in the Bay Area, Los Angeles, and Massachusetts. Some workers have begun calling them their “Jedi shields.”

Martinez has kept the printers humming for the past two weeks, and he has recruited another coworker, machinist Alejandro Saint Geours, to design an injection mold, which will help him produce shields five to ten times faster.

He has no plans to stop, as long as he is still able to get materials. Because this is a personal effort, with everyone involved donating time and resources, Martinez will need help covering the cost of materials—about $3.50 per shield in a run of 150—but he isn’t interested in any payment beyond that.

Had this 3D-printing effort not come together, Martinez says he would have hauled out his sewing machine, well used from years of sewing elaborate Halloween costumes for his children, instead.

“I would have turned my house into a mask-making factory,” he says, “and just put all my kids to work. In fact, my kids are at home right now waiting to assemble a bunch of shields. I’m not wanting to sit idle. When the world is falling apart, I just can’t do it.”

You Might Also Like