Sir Everton Weekes, West Indies batsman who was the most prolific of the ‘Three Ws’ – obituary

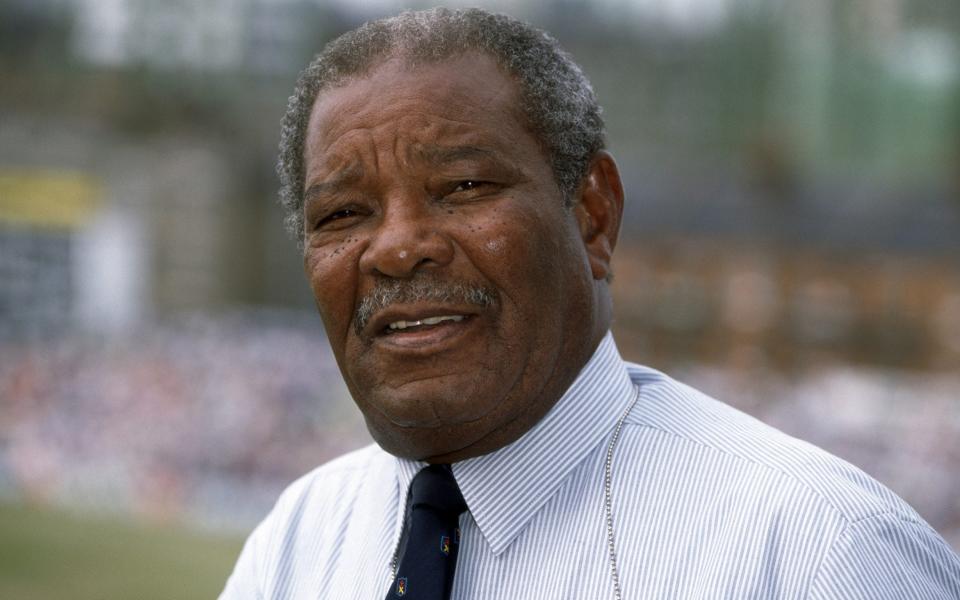

Sir Everton Weekes, the West Indian cricketer who has died aged 95, was the most prolific scorer of the “three Ws” – the others were Sir Frank Worrell and Sir Clyde Walcott – who were perhaps the most dominating trio of batsmen ever to appear in the same Test side.

Early in Weekes’s career, it seemed that his scoring feats might match even those of Sir Donald Bradman. There is a telling vignette of Weekes in 1950 when, having savaged the hapless Cambridge University bowlers to reach the 290s on a perfect wicket, he was unexpectedly beaten by a ball from John Warr.

“Play carefully, Weekes man, in the nineties,” he berated himself, and duly went on to 304 not out. The West Indies reached 730 for three wickets.

By mid-July that year Weekes had passed three figures five times, without failing to go on to a double century. In May, just before the game against Cambridge, he had smashed Alec Bedser and Jim Laker all round the Oval to make 232 against Surrey. The opposing captain was Stuart Surridge, with whom he had just signed a deal for the use of his name on Surridge bats. “Steady on, Everton,” warned Jack Parker from slip, “you’ll lose the contract.”

In June, Weekes hammered Nottinghamshire for 279 in 235 minutes. Old George Gunn, who had seen them all, from Victor Trumper to Don Bradman, thought that he had never seen such a dazzling array of shots, or heard the ball more sweetly struck. Someone asked Weekes why he had not gone on to beat Charlie Macartney’s record of 345 in a day at Trent Bridge. “Man,” he replied, “no one told me.”

Early July found the West Indies at Southampton, where Weekes hit 246 not out in just under four hours. In his next match, at Leicester, he raced to his hundred in 65 minutes (the fastest century of the season), and went on to double that total, while sharing in a stand of 309 in 150 minutes with Frank Worrell.

It therefore seemed extraordinary when, in the third Test at Trent Bridge, Weekes was caught and bowled by Eric Hollies on 129. Yet this was another thrilling innings.

He had been 90 not out when Alec Bedser took the new ball. The first three deliveries were rifled with thrilling power through the covers, one shot being hit so hard that the ball bounced 20 yards back off the boundary rail. There had never, declared Sir Pelham Warner, been batting to match that which Worrell and Weekes produced in their stand of 283 that day.

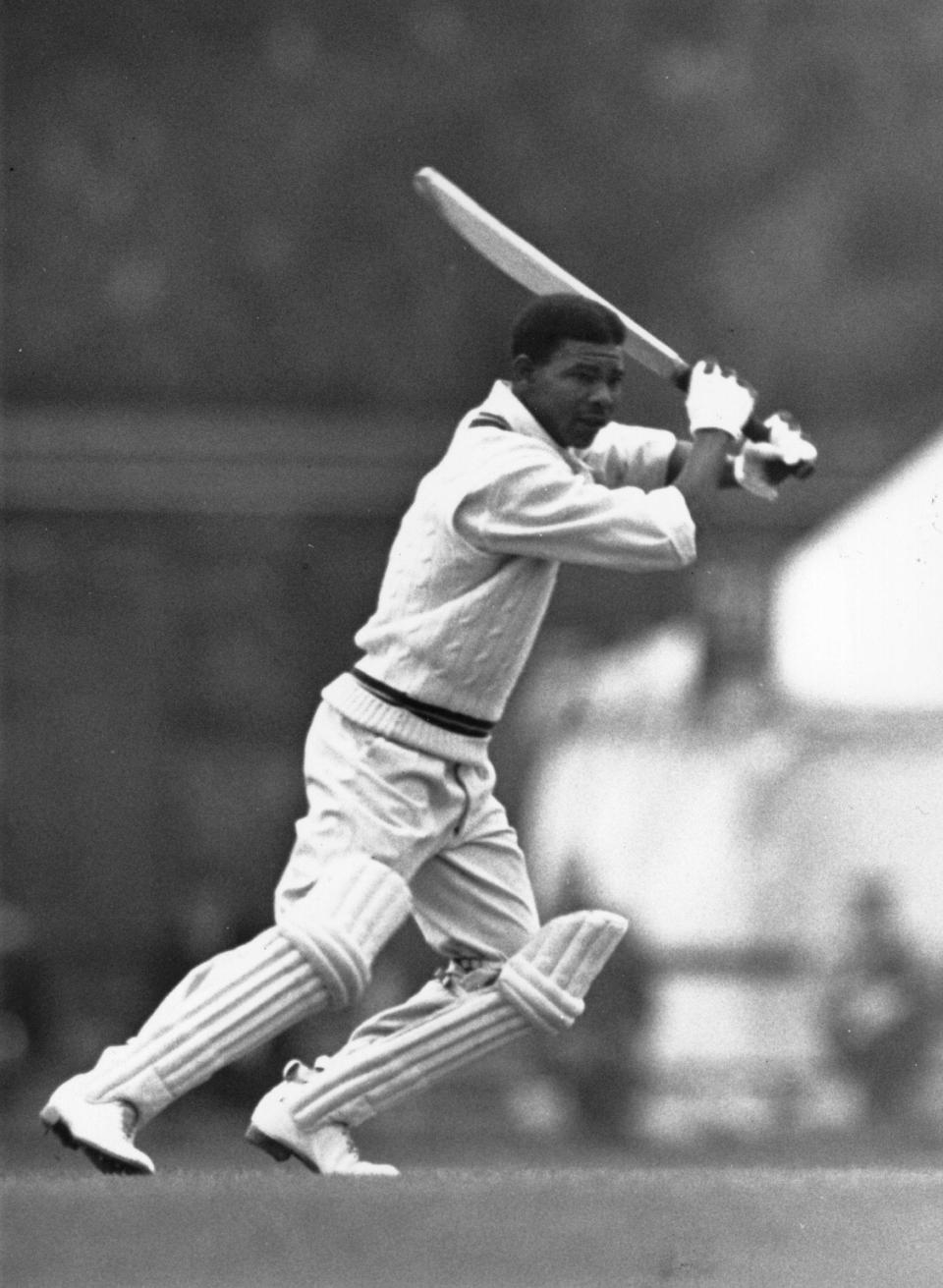

Weekes shared with Bradman the propensity not merely to master the bowling, but to destroy it. Short of stature, he excelled in whiplash cuts and fierce hooks against the faster bowlers, while he could drive with equal facility off both the front and the back foot. On form, he would make room for himself to hit the good-length ball seemingly at will to off or on.

If Weekes played defensively, C L R James wrote, it often seemed a last-second improvisation to a ball which he had at first meant to force away. Yet for all his unorthodoxy in attack, his defence was fundamentally correct.

In England in 1950 anything had seemed possible for Weekes. It had been the same in India in 1948-49, when he scored four successive Test centuries to add to the one he had already made against England in the West Indies. Indeed, he only missed a sixth Test century on the trot when he was run out – a bad decision – for 90 in the fourth Test.

But the magic faded during the West Indies’ tour of Australia in 1951-52. Weekes’s 70 in the second innings of the closely fought and low-scoring first Test was a typically stylish effort, but in the latter stages of that match he pulled a muscle when fielding in the slips, and for the rest of the series was obliged to bat with his thigh strapped up and the injured muscle shot full of anaesthetic. Deprived of his nimble footwork, he only made one more half-century in the series.

There were still many great innings to come, but with Weekes’s leg injury continuing to plague him it was never quite “glad, confident morning” again. As early as 1954 he talked of retiring; in fact he played Test cricket until 1958, bringing his total of centuries to 15 and amassing 4,455 runs at an average of 58.61. Among West Indian batsmen, only George Headley has a better Test average.

Everton de Courcy Weekes was born just down the road from the Kensington Oval in Bridgetown, Barbados, on February 26 1925, six months after the birth of Frank Worrell and 11 months before that of Clyde Walcott on the same island, which is no bigger than the Isle of Wight.

Everton was a cousin of Ken “Bam Bam” Weekes, who made 137 at the Oval in the last Test before the Second World War. Everton’s father, it need hardly be said, was a football supporter (Jim Laker once remarked to Weekes: “It was a good thing your father wasn’t a West Bromwich Albion fan.”)

Weekes first played cricket at St Leonard’s School. He was never coached, but during the war years, when he served with the Barbados battalion of the Caribbean Regiment without seeing active service, his talents caught the eye of E L G Hoad, a former West Indies Test player, and he was given a job as groundsman.

Clyde Walcott remembered that when he first came across him in a trial match in 1945, Weekes was known as an off-spinner who could bat a bit. Nevertheless, the year before, Weekes, aged 18, had made his first-class debut for Barbados as an opening batsman, and by 1947-48 he had done well enough to be selected to play for the West Indies against Gubby Allen’s weak English side.

In his first five Test innings he got himself out in the 20s and 30s, so that he was dropped for the fourth and final Test. In the event, though, George Headley proved unable to play, so Weekes was reselected. This time he scored 141.

In 1949 he accepted an offer of £500 to play for Bacup in the Lancashire League, and would play for them for seven seasons between 1949 and 1958. Early homesickness was tempered by his landlady’s potato pies – and the presence of Worrell and Walcott, who were turning out for Radcliffe and Enfield respectively.

Playing for West Indies in 1948-49 Weekes averaged 111.28 over five Test matches in India, without the benefit of a single not-out decision. Though the Indian attack lacked fast bowlers, Vinoo Mankad was the best left-arm spinner in the world, while Dattu Phadkar and Lala Amarnath were useful seamers.

Weekes again averaged over 100 when the Indians toured the West Indies in 1953-54, and the next year he scored 206 against England at Port of Spain. In 1954-55 he redeemed his earlier failure in Australia by making 469 runs in the home series.

But he failed against England in 1957, with the notable exception of his 90 on a dangerous wicket at Lord’s against Fred Trueman, Brian Statham and Trevor Bailey – “an innings of genius”, Denis Compton called it. Although he scored freely against Pakistan that winter, he decided, at only 32, to retire from Test cricket.

He continued for a while to play for Barbados, scoring many runs and proving a canny captain. In 1962 he toured East Africa, India, Pakistan, Hong Kong, Australia, New Zealand and Rhodesia with R A Roberts’s multi-racial side. When he shared a taxi with Neil Adcock and Roy Maclean, the driver asked if they all played for South Africa. “Man, are you colour blind?” Weekes replied. He was always the readiest to laugh of the three Ws.

For a time in the 1960s Weekes was a government-appointed cricket coach in Barbados. He toured with MCC in Canada in 1967 and coached the Canadian side at the 1979 World Cup.

Weekes was a brilliant fielder, fleet of foot in the covers, and with exceptionally safe hands at slip, and was immensely popular wherever he went. But he lacked the instinct for leadership of Worrell, who became one of the great captains before his death in 1967, and the administrative competence of Walcott, who chaired the International Cricket Council.

Weekes, by contrast, ran a nightclub in the 1970s, and showed his brains by becoming an international bridge player, turning out for Barbados against his old cricketing foes, England, Australia and India. He swam every day until 2017, when he was advised to give it up: “The doctor thinks drowning is not a very pleasant way to go,” he remarked.

Everton Weekes was appointed OBE in 1960, and was later awarded the Barbados Gold Crown of Merit; in 1995 he was knighted.

His son, David Murray, played 19 Tests for West Indies but was banned for life after going on a rebel tour of South Africa. Murray’s son, Ricky Hoyte, played for Barbados and for the West Indies “A” team.

Sir Everton Weekes, born February 26 1925, died July 1 2020