She hopes CARE Court will save her husband. Two months in, she's waiting for answers

Maria Macias pulled into a parking space at the Los Angeles County Superior Court in Norwalk. She had come from Gardena and found herself praying for strength during the drive.

“It is too easy to fall into the sadness of it all,” she said, “too easy to hide and not face every day.”

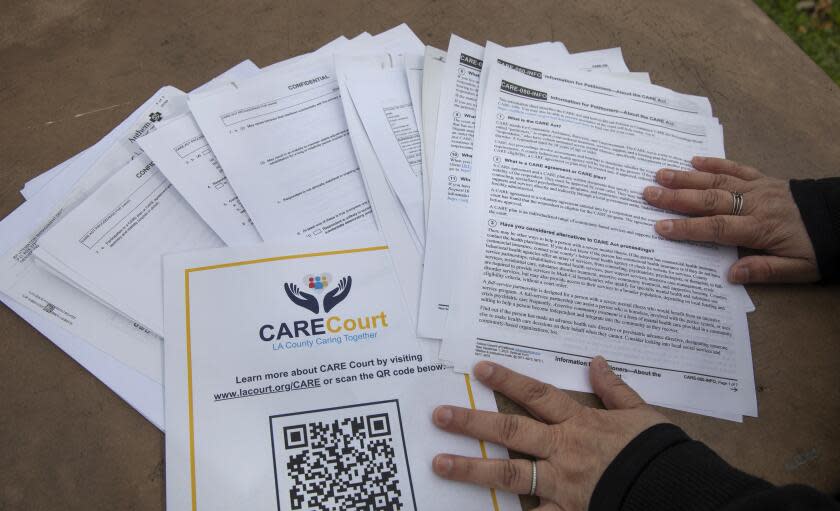

On the seat next to her was a six-page petition asking the court to provide a treatment plan for her husband, whose schizophrenia and drug use endangered his life and had left them estranged.

For at least 20 years, Macias said, she has lived with the fear, uncertainty and sorrow occasioned by his mental illness. Although they are not divorced, their marriage in effect ended when she had to file a restraining order to keep him from harassing her and their three sons.

But on Dec. 1, the day CARE Court opened in Los Angeles County, she believed their lives might change.

Signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom in 2022, the CARE Act is a radical rewriting of the state’s behavioral healthcare law that for the first time gives family members an opportunity to request treatment for spouses, children or relatives experiencing severe psychiatric distress.

It works this way: A person requesting a treatment plan for a loved one submits a petition, which is considered by a CARE Court judge and, if approved, sent to a county’s department of mental health. The department has 14 days to contact and assess the person needing help before scheduling a court hearing to outline a treatment plan.

Macias, first in line that Friday morning, believed her husband, whose name she asked to keep private, would be a perfect candidate for the program. But more than two months later, she is less certain. She feels as though she’s being kept in the dark.

Despite providing her husband’s psychiatric history and updates on where he is living, and being available for questions or clarification, she has no idea whether her petition has been accepted.

She has received two emails from the court — legal forms signed by a “supervising psychologist” twice extending the deadline for the L.A. County Department of Mental Health to engage with her husband — with no explanation why.

Then, on Tuesday, she received a phone call from a caseworker. The news was not promising. He had questions about her husband and concerns about the admissibility of her petition.

She felt her spirits sink. Weeks of hope were turning to resignation.

“You go to the court, you submit the paperwork they ask for, and there is no communication, no explanation for what’s going on. You’re left to wonder what more you can do,” she said. “What more could I have done? You end up doubting yourself to the point where you just have to let it go.”

Macias is one of more than 60 petitioners to CARE Court since it opened in L.A. County, and her experience offers a glimpse into the challenges faced by families and by the Superior Court and Department of Mental Health in trying to meet the ambitious goals set by the state.

The Department of Mental Health declined to comment on the status of her petition, but Martin Jones, who oversees the CARE program there, offered a caveat.

“We’re doing our best and in good faith want to assist and support everyone in this process,” he said, but “the CARE Act program is not a panacea, and we have to be honest about that. It is a valuable tool to use with a myriad of other programs.”

::

Macias was hopeful when she stood in front of the tall, stone courthouse, clutching the petition. She was going to file online but wanted to leave nothing to chance.

She had photocopied the form four times, clipped everything together and tucked it into a large FedEx envelope, along with referrals, letters and a chronology of her husband’s sickness.

“I love him,” she said that morning, fighting back tears. “I know the man he was before the psychotic episodes. No one else knows who he really is.”

When the CARE Act became law, it promised to jump-start the state’s lumbering mental health system. Two other bills followed. One adds substance use, such as methamphetamine addiction, to the criteria for holding someone against their will and will be implemented in L.A. County in 2026. And in March, voters will decide on Proposition 1, a measure that would reform the state’s 2004 Mental Health Services Act and, with a $6.38-billion bond measure, help build and fund treatment facilities.

Yet will their promise — to provide meaningful aid to those with severe mental illness — be realized? Or will legislated treatment exacerbate mental illnesses, as some critics argue?

Two years ago, Macias knew she had to help her husband. She joined a support group run by the National Alliance on Mental Illness and in October filed for the state’s Assisted Outpatient Treatment program, but the county Department of Mental Health failed to engage with her husband.

“He’s a runner,” she said. Since she pays his health insurance, he moves in and out of unlocked facilities. When he gets unruly, they discharge or hospitalize him. He lives on the streets until he gets picked up again, repeating the cycle.

Maybe CARE Court will be different, she thought. Maybe the court will compel the Department of Mental Health to help him.

“I believe that once he is in a safe place, consistent with his meds, in group therapy, it will help him,” she said. “Maybe we can reconcile and bring our family together.”

Standing in the chill before the courthouse opened, Macias leafed through the petition detailing her husband’s psychiatric history. When he was younger, he was addicted to methamphetamine, she said, but they soon learned that drugs were not the only reason for his unpredictable behavior.

After one hospitalization almost 20 years ago, he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia with underlying depression, and for a while, his psychotic episodes seemed manageable with treatment.

Then he took a job working the graveyard shift as a truck driver at the port. The family was living in an apartment in San Pedro and had fallen into debt with Christmas gifts, clothes for the boys and vacations. As they struggled with bills, the stress and lack of sleep took a toll.

The paranoia and delusions surfaced.

“Dad isn’t Dad anymore,” Macias recalled one of their sons saying.

Inside the courthouse, employees were stringing Christmas lights. Macias paused at a directory and saw that the CARE Court was in Department B, second floor.

Not long after the passage of the CARE Act, seven counties opted to open their courts in October. The rest were given until Dec. 1, 2024, and L.A. County could have waited, but the Board of Supervisors voted for an earlier rollout.

Only Supervisor Lindsey Horvath dissented, “concerned by the rushed decision to join the program.”

“Without proper investment and clear direction,” she said in January 2023, “this system will run the risk of breaking the promises that we have made to L.A. County voters to deliver real, meaningful progress and change.”

According to a spokesperson, her opinion is unchanged.

Two months in, the Department of Mental Health understands the frustration of petitioners like Macias, Jones said, but the rollout is on track.

“The process of outreach and engaging does take time and multiple attempts,” he said. If anything, the 14 days for outreach and engagement “is ambitious, but the fact we can extend the time is helpful.”

As of Thursday, his department had received 61 petitions — a number he said is steadily rising —and had scheduled five hearings, a crucial step before writing a treatment plan, known as a CARE agreement, which includes not just psychiatric services but also housing and legal representation in court.

“If you check back in two or three months, we will have some different numbers to share. This is all evolving. Every day it’s changing,” Jones said.

Among the earliest launching counties, San Diego has approved 72 petitions and written 19 agreements ; Riverside has approved 33 petitions and written three agreements ; Orange has approved 29 petitions and written four agreements ; and Stanislaus has approved 18 petitions and written seven agreements .

On the second floor, Macias sat on a bench in a long, empty corridor and waited for the court to open. A sheriff’s deputy walked up and explained that petitions first had to be reviewed on the seventh floor.

“Good luck,” he said. “You are literally the first one.”

::

Her husband’s illness was most wrenching for being unpredictable. Some days he seemed lucid, as painful as it was, such as the time he told her he wanted a divorce, said she was holding him back and moved in with his parents.

But then he struck his father and ended up outside her apartment at night, throwing rocks at the windows, playing loud music. She called the Sheriff’s Department.

“You can’t keep calling us,” deputies told her.

On the seventh floor, she found the CARE Court self-help center.

Entering a small gray office, she was greeted by four court employees, who read her petition and told her that the next step would be to file it with the clerk on the first floor.

They then introduced her to two representatives of the Department of Mental Health, who asked a few questions about her husband. Was he receiving services? No. Was he connected with any service provider? No.

Satisfied, they told Macias what she should expect if her petition was accepted: a hearing, a treatment plan, a possible appointment in the court. The details soon overwhelmed her.

“We admire your courage,” one said, as she started to cry.

Standing again in an empty corridor, she wiped tears from her cheeks.

Her husband had once been so patient and loving. He listened to her when she needed to talk to someone. He was attentive to the getaways she planned for themselves as a couple, and he was a good father, standing on the sidelines when their sons played football, taking them to sporting events, to SeaWorld, so easily expressing his love.

She felt she was betraying him.

“I just want to crawl back into bed and hide,” she said. “But I’ve got to compartmentalize this. I have to go to work.”

On the first floor, she handed her petition to a clerk at Window 3, who entered information into his computer, then grabbed the self-inking stamp and pressed it on the square reserved for court use only.

Macias reached into her purse but was told there is no filing fee.

Outside, she took a breath in the morning light. The 14-day clock would start as soon as the judge accepted the petition.

“It feels good,” she said. “This is a sickness in him, and I want him to get well.”

::

Two weeks later, she had heard nothing. She called the Superior Court and was told that her case had been referred to the Department of Mental Health but that no hearing had been scheduled. Had her husband qualified? They didn’t say.

Then he showed up at her home. It was past midnight. He had run away from a hospital before it could start a 72-hour mandatory hold. Macias called the police, and he was picked up for trespassing and taken to jail in downtown Los Angeles.

Macias called the Department of Mental Health; she thought a caseworker could evaluate him while he was being held. The person who answered the phone took the information. What was done with it, Macias never learned.

She continued to try to help, calling the department whenever her husband’s address changed, but when she asked about the status of her petition, she was told that privacy laws prohibited discussing the status of her petition.

In the meantime, her husband continued to run. Released from jail, he had tried to visit a friend in Mexico but couldn’t cross the border and came back to the Los Angeles area, living in Redlands, then Covina and now a behavioral health facility in Mission Viejo.

Macias didn’t understand why caseworkers were taking so long to contact him. After the second deadline extension expired Jan. 29, she had heard from no one.

“It is very, very frustrating,” she said. “Sometimes I feel like going outside and screaming my head off.”

Then Macias got a call from a caseworker with the Department of Mental Health, who expressed concerns that her husband was living outside L.A. County and receiving services. This would disqualify him.

Macias tried to explain and was waiting for a call back when she received an email from the court granting another extension, this time until Feb. 29.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.