I Saw the Future Standing in Line for Weed in Illinois. Then I Drove Back to the Past.

For some reason, I live in rural west-central Indiana. While my home sits a mere twenty-six miles from the western edge of Indianapolis, I can’t stream movies or find reliable cable or buy fresh fruit in town. It’s a mashup of a past I can remember with a few facts of now. Say 1973, with cell phones. Like 1986, with Facebook. Whatever.

The present is always a long way off in the American hinterlands.

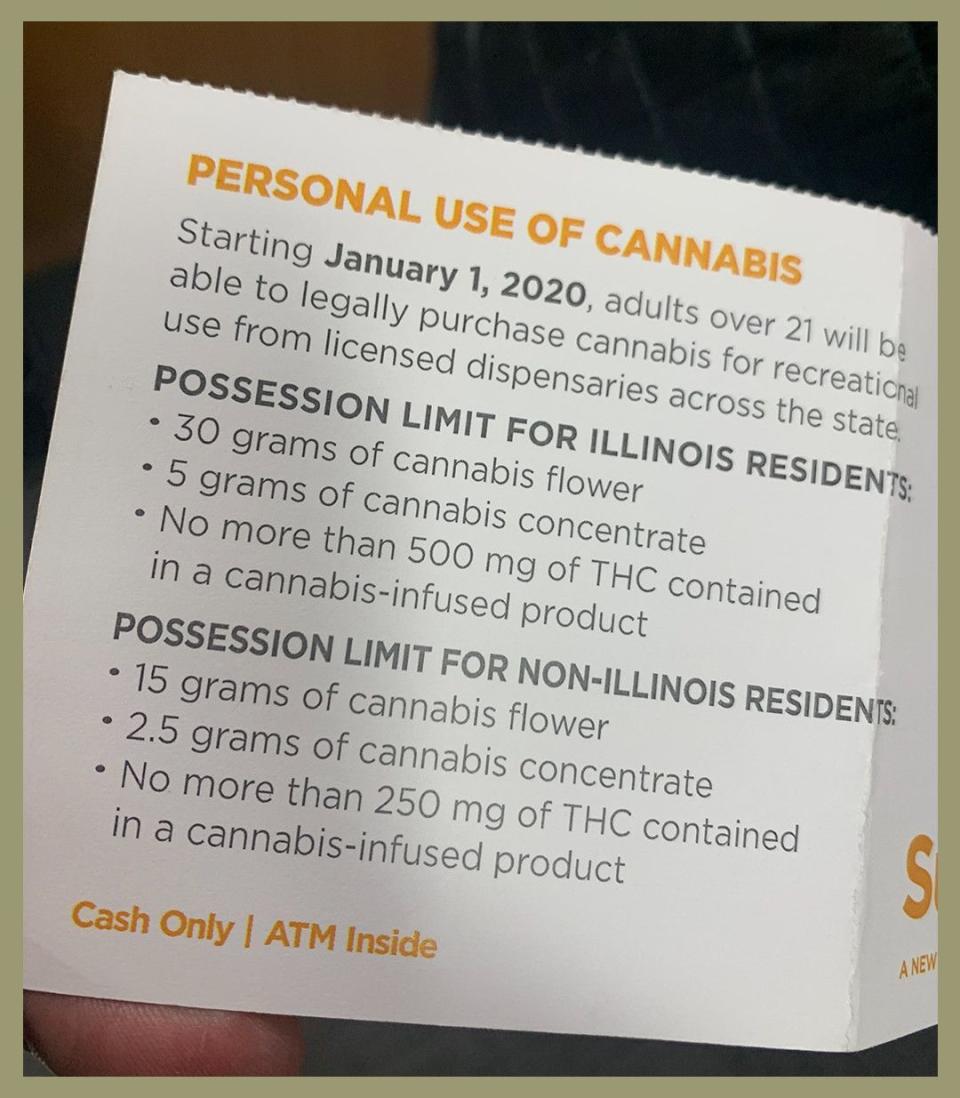

But sometimes, despite all the distance, the fact of the now rushes right up and jumps on you. Last Friday, two days past New Year, my 24-year-old daughter and I decided to drive to Illinois to buy recreational marijuana, which had been legalized in that state for just one full day. Illinois sold $3.2 million dollars of legalized product when they did this one other time. Spirits were high. Lines were long. Supply was reported to be good.

So 101 miles—county road, state road, interstate—westward over the state line, past grain silos, flea markets, Amish groceries, through the flickering fluorescent landscape of Indiana. Destination: the Sunshine dispensary, in Champaign, set snug in an old office complex, amidst mortgage companies, fast-food joints, and used-car dealers. We wanted to be there when it started. Something was happening there. We wanted to see a little history.

And I’m only too happy to admit that I also wanted a little bud.

In Champaign, we jaywalked across five sizzling lanes of traffic to join the stacked-up line of two or three hundred souls waiting to be lead into a tent. It felt like a concert, only no music. You could hear the chatter of the line from across the street. Passing cars blew their horns. Fists were raised from the windows of dented Mazdas. Onlookers stood gawking at the people in line. Every twelve minutes, customers were led from the tent in groups of seven to the doors of the dispensary.

Even so, the line did not much appear to be moving. My daughter and I clicked in at 3:20 PM and the off-duty policeman working the event informed us were lucky. “You’re the last ones we’re letting in line,” he told me.

“What time does the dispensary close?” I asked.

“Ten o’clock sharp”—a point in time almost seven hours from that moment. This was late afternoon, early January in mid-state Illinois, Central Standard Time, where the sun goes down before five. The clouds sat like slate above us, the air stood blue with cold. A wind started up. My knees buckled a little.

“Are you saying we’ll be the last ones in?” I asked.

“If you’re lucky,” the cop told me. “They can’t sell anything after 10.” He regarded the crowd and shrugged. “We can’t guarantee you’ll get through.”

“Are you going to be standing here for seven hours too?” I asked.

“Not me,” he said. “I’m going to lift in half an hour.”

My daughter wanted in. In on the experience of the line, the purchase, the sight of the catalogue, the bins of promotional stickers, the order form, the delivery of edibles from mysterious inventory lockers, the barcoding of product, the absolute normalcy of commerce laying like a shroud atop the moment of the buy. And the sight of cops standing watch—inert, good humored, unconcerned. My daughter was down for the wait. She’d lived in Indiana all this time. She had yet to purchase legal weed, legally. She just wanted to be around for the moment of the now. To her the moment felt generational, historical. Important.

I lived in Boulder for a spell, and I’d written a book which I’d researched in Seattle. I had experience with dispensaries. There was no magic in the purchase for me, since I’d bought weed merely two weeks before, legally, in Michigan. Fact is, I was holding.

I walked the line twice in the first hour, talked to everyone I could. Like all crowds of pot smokers, these people were absurdly diverse. And happy. The blind. The deaf. Wheelchairs. Married couples. College roommates. Veterans. A young man with a cane. A retired firefighter and his son. Two pods of insurance salesmen who’d taken the afternoon off. A real-estate agent. Two engineers. A psychologist. Two clerks and a groomer from Pet Smart.

No one there cared one bit about the tortured pace of the line. It was an army of fleece. They wore ski caps, ball caps, pullovers, hoodies, work gloves. They were talkative. Optimistic. Pleasant. Everyone was in for the duration.

Buying pot has always been a bullshitter’s paradise. People wanted to show they understood the game a little better than anyone else. They liked the weed better in Toronto than in Colorado. Prices were better in California now. They babbled about indica and sativa; chattered about brands of vape. They shared pictures of their bongs. Did I have the weedmap app?

Was I ready? Could I keep up?

I’d started smoking in the 80s, and settled out of it in the 90s when my career began in earnest. I picked it back up in Colorado a few years ago, and left there hoping that decriminalization/legalization would spread reliably across the country. That had always been my hope.

It got dark. Cold. People talked louder, smoked cigarettes. They held spots when others needed a break. They brought each other coffee. Somebody unaffiliated with any donut company walked through with donuts in a huge flat box. People shared.

Early in the evening, the police turned their attention to the jaywalking that was occurring from nearby parking lots. If it persisted, we were told, the line to the dispensary would be closed down. So it was that I witnessed the weirdest assertion of law and order I’ve ever seen: 150 people waiting to buy pot, chanting “Don’t Jay Walk!” to anyone crossing outside the distant cross walks.

Even the cops were laughing.

Eventually the glacial progress of the line made me antsy. I’d waited long enough. For all its esprit-de-corps, the line just felt like one final insult. I was experiencing a larger brand of cultural impatience. I live in Indiana, amongst farmers, men and women who grow things for a living but want no part of hemp because it means more connection to the government rather than less. The Republican-led state government has pretty much declared that legalized marijuana won’t be coming to my home state anytime soon. Senate President Pro-Tem Rodric Bray (you can’t make this up) was quoted in the Chicago Tribune as being opposed to legalizing “a second type of cigarette” while the state is considering raising the age for smoking tobacco to 21. He went on to voice his suspicion that marijuana legalization will have an impact on “the productivity of our citizens in the workplace.” Heavens!

I’ve spent most of my adult life living thirty miles from the future.

I love Indiana. I love my house, and value my land. I live above a beautiful creek, with a good view of the sunset. I have two excellent dogs. I have my friends. But the longer I stood in line there in Illinois, the more I hated what I had to go back to.

I’ve stood in line plenty in my life. (Four hours for Clash tickets; nine hours for baseball playoff tickets; two-and-a-half for a hug from a Hindu healer). One way or another, you always get there.

The line moves.

Change comes.

But maybe I didn’t need to witness it if it meant seven hours standing in the cold. At 5:45, I left my daughter to stay the course, to hold our spot, to be amongst her tribe. I went to the movies.

I returned two hours later, wound up the last person admitted two hours after that, at 9:50 PM. It turned out, I was the last purchase in the dispensary, likely the last transaction rung up in the state that day. The staff applauded. It felt big. I waved back. I bought edibles. I spent just ninety bucks on what I consider to be the best cough drops ever.

But I left angry. For these people, the wait was over. Illinois. Bah! They’d made it through, arrived in some part of the future. I was being forced back into a line, to wait for a change that is working everywhere else.

We limped back all 101 miles. We left behind the present, and returned to land of the not-so-recent past, to Indiana, where it’s 1983.

And counting.

You Might Also Like