Researchers Have Discovered a Hidden Drawing Behind ‘Mona Lisa’

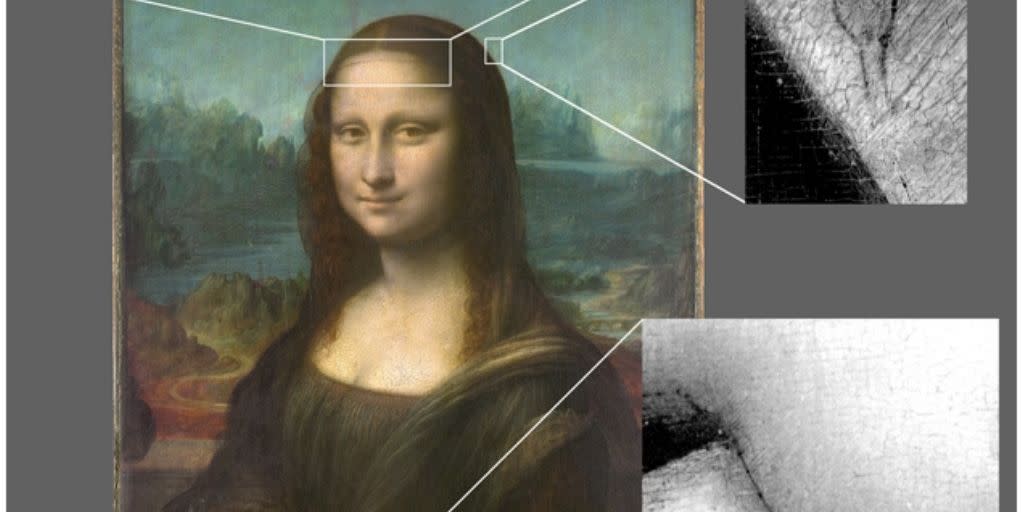

Camera study over many years has revealed that Mona Lisa has a spolvero underdrawing.

Master painter and multihyphenate Leonardo da Vincic used a kind of tracing that copies sketches.

The camera identified telltale markings beneath lighter portions of the famous surviving version.

For the first time, research 16 years in the making has shown the Mona Lisa has an atypical, groundbreaking planning drawing underneath. The technical term for the underdrawing is spolvero, an Italian term of art referring to a charcoal guiding sketch created by a form of stenciling. The paper went online in August and appears in the Journal of Cultural Heritage.

We love to understand the amazing things about science. Let's explore it together.

“On the request of the Louvre Museum, Mona Lisa’s portrait was digitised with Lumiere Technology's high-resolution multispectral camera,” the researchers explain in their paper:

The camera beamed infrared light that illuminated every layer's nooks and crannies, and then an algorithm took the faintest traces and made them more visible. Let’s break down some concepts. What is spolvero, how is it different from just tracing, and how is it identified in particular with this camera? Also, why did Leonardo da Vinci use it? Take a deep breath and we’ll learn all about planning a painting.

The big part of this finding isn’t that there is a planning element underneath—that’s a key part of almost every painting ever, especially ones that are figurative like the Mona Lisa. The point of this painting is to resemble real life and capture a likeness. When you see painters hold up their brushes with their thumbs carefully positioned, they’re eyeballing the distances between different features or objects in order to correctly scale how they paint these objects.

Master painters often made several versions of a particular composition they wanted to make, let alone the paintings they often scratched off in order to start completely over. They may want to make a new version for a new patron, for example. This is where the idea of a spolvero comes in.

Once an artist had a likeness they were happy with in sketch or painting form, they could trace over it using a sheet of tissue-like thin vellum, for example. And then they could puncture the paper with tiny holes that would allow through enough charcoal dust to make a fresh outline of the existing work. It’s a very low tech version of how screenprinting works—or even a Lite-Brite.

This is where the infrared reflectographic camera technology comes in. By optically “piercing” the painting with harmless light beams, researchers can see where da Vinci’s pierced spolvero deposited the underlying sketch. ArtNews reports:

“[Researcher Pascal] Cotte detected the spolvero marks in the Mona Lisa’s hand and hairline—the lighter areas of the painting—which revealed that Leonardo shifted her pose, turning her head to stare more directly at the viewer. The study also stated that the drawing may have been used to create more replicas of the painting, such as the one displayed in the Prado in Madrid, which owns the earliest known studio copy of the Mona Lisa.”

Cotte told ArtNews that the most interesting takeaway could be to somewhat deflate the emphasis on a single version of a masterpiece, instead stoking “the mystery of its creation” as the result of years of careful work, planning, and iteration.

Even the masters didn’t put paintbrush to canvas and cough up enduring enigmas on the first try.

You Might Also Like