Puncture-Proof Tires Are the Future

At the University of Illinois Department of Aerospace Engineering, researchers used computer simulations and algorithms to help find the best structural patterns for use in a non-pneumatic, puncture-proof tire.

The scientists' findings appear in the International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering.

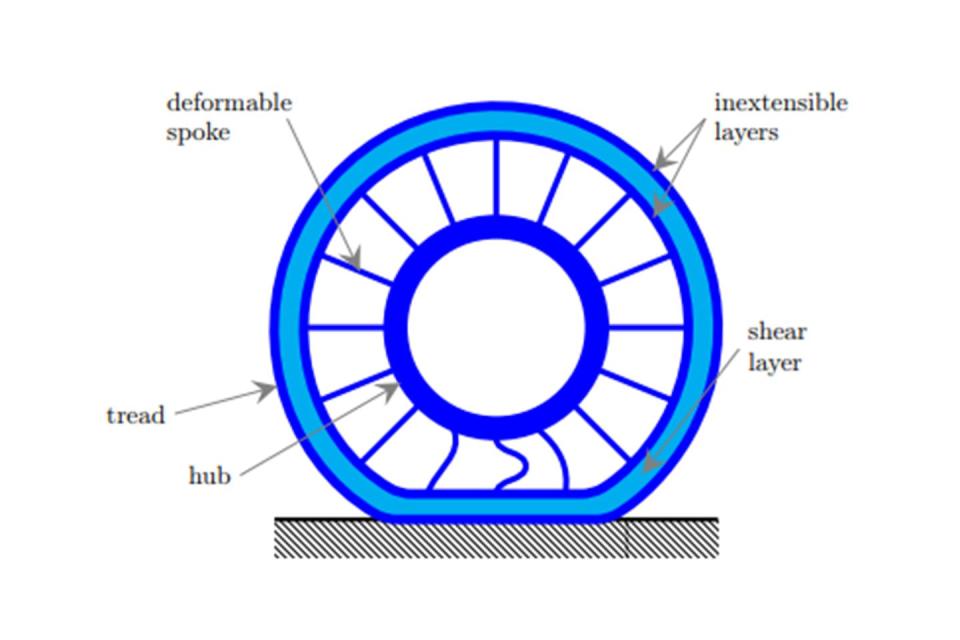

It turns out the shear layer, just beneath the tread, is the most forgiving part of the tire, stretching to meet new design requirements.

Surely you've seen the light: You're enjoying a regular, run-of-the-mill drive when suddenly, seemingly out of nowhere, your tire pressure light begins to glow orange. Upon inspection, you find a nail has deflated one of your tires.

It's an all-too-common tale, but researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign are hard at work on a potential solution: a puncture-proof tire.

Yeshern Maharaj, a former master's student at the university's Department of Mechanical Engineering, and Kai A. James, an assistant professor in the Department of Aerospace Engineering, looked at ways they could design an airless tire that still had enough give to provide a shock-free ride. They published their results in the International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering.

They quickly narrowed in on a tire's shear layer, which is just below the tread in a non-pneumatic tire. In an April 2017 patent application on behalf of The Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, the inventor, Francesco Sportelli, writes that the purpose of the shear band is to "transfer the load from contact with the ground through tension in the spokes or connecting web to the hub."

As this shear band deforms, it causes a change in shape of the structure, rather than bending. This is why James, one of the paper's coauthors, says it's the best part of the tire to tinker with as an engineer.

"The shear layer is where you get the most bang for your buck from a design perspective," he says in a press statement. "It’s where you have the most freedom to explore new and unique design configurations."

James and Maharaj used design optimization, an engineering methodology that relies on software to help determine which design parameters will lead to the best performance of a structure. Here, they wanted to come up with a few different structural patterns for the shear layer. They used a computer simulation to model the elastic response of the shear layer, meaning the way it twists and stretches. The goal was to find a structure that could withstand strain while under pressure, while creating stiffness in the axial direction.

"Beyond a certain level of stress, the material is going to fail," James said. "So we incorporate stress constraints, ensuring that whatever the design happens to be, the stress doesn’t exceed the limit of the design material."

The researchers also focused heavily on buckling constraints. If a strut is undergoing compression, it could fail, so James and Maharaj had to mathematically predict what level of force would introduce bucking and modify their design accordingly. The aim, when finished, is to create a tire that can both withstand pressure and provide a comfortable ride that doesn't feel like driving on four metal blocks.

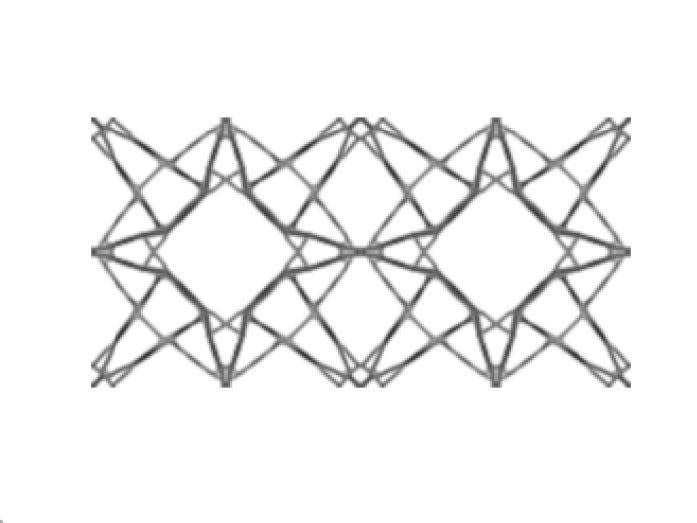

In the computer simulation, structural designs that could fail—or at least aren't optimal—are slowly eliminated. The computer starts out with a block of the bulk material that the tire will be made of and slowly strips away parts of it. It's a balancing act to find the right level of elasticity with the right level of structural integrity. If you carve holes into the material until it looks like a chessboard, you're going to walk away with half of the original stiffness, James points out. A more complicated pattern will be more nuanced.

"Search algorithms have clever ways to strategically search the design space so that ultimately you end up having to test as few different designs as possible," James says.

"Then, as you test the designs, gradually, each new design is an improvement on the previous one and eventually, a design that is near optimal."

For now, pneumatic tires are still more popular than any non-air-filled competitor, and James says that for future research, the university will need an industry partner. However, these puncture-proof tires could be on the horizon, as some golf mowers, lawnmowers, and even one major tire company, Michelin, are already using airless tires. In the meantime, keep a donut handy.

You Might Also Like