Psychedelic mushroom edibles promise health benefits. Be wary, experts say.

The chocolates and gummies come packaged in retro trippy colors, adorned with melting mushrooms and surrealistic landscapes and flavored like children’s breakfast cereals. The labels promise all-natural, mind-bending trips and boosts of mental clarity, creativity and focus.

Sometimes, these psychedelic sweets are more harmful than healthy.

Public health experts and officials are amplifying their warnings about the risks of unregulated and sometimes illegal products advertised on social media and easily purchased online or in vape shops. Some claim to contain the hallucinogenic mushroom compound psilocybin, which is legal for use in two states but illegal federally. Some products contain potentially harmful synthetic chemicals or extracts from a sometimes-toxic mushroom known as amanita muscaria.

Labels can’t always be trusted, said Eric C. Leas, an assistant professor at the Herbert Wertheim School of Public Health at the University of California at San Diego.

“Consumers have a right to know what they are getting when they consent to a psychedelic experience,” Leas said. “It’s not fair to them to not know what’s in their mushroom gummies or chocolates.”

The warnings have sharpened in recent weeks as state and federal health authorities say they are investigating the mushroom edibles brand Diamond Shruumz after nearly 50 people in two dozen states fell ill from its products. Investigators are also reviewing one death associated with the outbreak.

The maker of Diamond Shruumz, Prophet Premium Blends, has initiated a nationwide recall of the products, acknowledging some contained high levels of a potentially toxic chemical found in the amanita muscaria mushroom.

The company said in a statement posted on its website that “it is crucial that all of our consumers refrain from ingesting this product while we, alongside the [Food and Drug Administration], continue our investigation as to what is the cause of the serious adverse effects.”

The unregulated industry is expanding on the coattails of much-publicized and promising research into using psilocybin and psychedelics as medicines. The FDA in one case has deemed psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression a “breakthrough therapy,” a designation meant to accelerate research. Companies and governments are pouring millions of dollars into researching psilocybin for treating post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental health conditions.

Magic mushrooms are enjoying a cultural moment as enthusiasts, including some celebrities, tout their benefits and advocate microdosing - taking a tiny fraction of the typical dose of a psychedelic used for clinical effect.

Some states are legalizing, or considering legalizing, psilocybin use. Utah lawmakers recently authorized a pilot program allowing supervised administration of psilocybin to treat behavioral health disorders at certain health-care systems. In Oregon, under a pioneering law passed by voters, psilocybin can be administered for therapy at nearly 30 state-regulated service centers. The state’s health authority has registered more than 300 “facilitators” trained to supervise patients.

The treatment can cost thousands of dollars - making it unaffordable for many users and potentially turning people to the gray market.

A law similar to Oregon’s passed in Colorado, where personal growing, use and sharing has been decriminalized but where it remains illegal to sell psilocybin. Cities including D.C. and San Francisco have categorized mushrooms as a low priority for law enforcement, allowing products to flourish.

The patchwork of laws and regulations mirrors the early days of state-legalized marijuana and the gray market for intoxicating products made from legal hemp, experts say.

“There is a lot of confusion in the marketplace right now because there is a lot of demand for these natural medicines, in part because a lot of people have found a lot of healing in them,” said Colorado attorney Joshua Kappel, who helped draft his state’s law legalizing use of some psychedelics as medicine.

Chelsea, a 32-year-old San Diego tech worker, is careful about where she buys her magic mushrooms. She attended a life-changing “mushroom retreat,” now takes a couple of grams every few months and appreciates the clarity and focus the psychedelic trips instill. Chelsea prefers ordering online from a Michigan mushroom chocolate maker - vouched for by, of all people, her parents.

“I only buy if it’s recommended to me by someone who has taken it,” said Chelsea, who spoke on the condition that she be identified by only her first name because of concerns that her employer might frown upon her occasional use.

- - -

‘Really agitated’

Psilocybin has surpassed ecstasy as the most popular psychedelic, although users report consuming it infrequently and most often in microdoses, according to a report released last week by Rand, a nonpartisan research organization. Researchers estimated U.S. residents spent $1 billion on psilocybin in 2023. Among people surveyed who used it in the past year, more than 22 percent consumed the drug in edible form, the survey found.

The U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime, in an annual report released June 26, also raised concerns about the “psychedelic renaissance” leading to companies taking part in an “enabling environment that encourages broad access to the unsupervised, ‘quasi-therapeutic’ and nonmedical use of psychedelics.”

In Australia, health officials in late June warned of a brand of mushroom gummies - that were marketed as not being psychedelic - after consumers were hospitalized with vomiting, twitching and “disturbing hallucinations.”

In the United States, FDA and state health officials have warned against eating Diamond Shruumz brand “microdosing” chocolate bars and gummies after at least 48 people in 24 states grew ill - 27 of whom were hospitalized, according to a July advisory. Officials report people passed out and experienced seizures, loss of consciousness, agitation, nausea and vomiting. Some had to be intubated.

“Some people got really agitated to the point they had to be given medicine to sedate them before they hurt themselves,” said Christopher Hoyte, medical director of the Rocky Mountain Poison & Drug Safety Center in Colorado.

The maker of Diamond Shruumz had advertised its products as having no psilocybin. But the FDA said two chocolates have tested positive for 4-AcO-DMT, a synthesized chemical related to psilocybin that produces similar effects. One chocolate also contained compounds found in the kava plant, which is sold as an herbal supplement and marketed to ease anxiety and insomnia but has prompted warnings about possible liver damage.

Nationally, while still low, reports of mushroom poisonings are rising. In 2023, there were 1,005 cases of people sickened by psilocybin - and not in combination with any other drugs - more than triple in 2019, according to America’s Poison Centers, which tracks data from regional poison control centers.

Experts have warned that people with histories of mental illness may be vulnerable to breakdowns, even if the immediate effects of the mushroom products have worn off. An off-duty Alaska Airlines pilot was arrested last year after he allegedly tried to cut the engines during a flight bound for San Francisco - an action his attorneys said resulted from the pilot taking a small amount of psilocybin two days earlier.

“In combination with other drugs, it can lead to some troubling psychological and psychiatric outcomes” outside of therapeutic settings, said Joshua S. Siegel, a psychedelics researcher at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

- - -

The warden and the Uber driver

Beyond the pilot, most high-profile arrests involve sales of illicit mushrooms that can be used to make edibles, put in capsules or made into teas.

Consider the Alabama prison warden and the 21-year-old Connecticut man, accused in separate cases of growing illegal mushrooms in their homes. Or the Florida Uber driver charged with selling shrooms to undercover detectives in town for a narcotics police conference. And the Jacksonville, Ore., man who the feds say used the encrypted chat app Telegram to sell bulk “penis envy” mushrooms across the country.

Seizures of psilocybin increased by 369 percent between 2017 and 2022, according to a February study by researchers at New York University Grossman School of Medicine, suggesting the illicit market - and possible health risks - are growing. Lead author Joseph J. Palamar said Oregon appears to be a hub for products bound for other states.

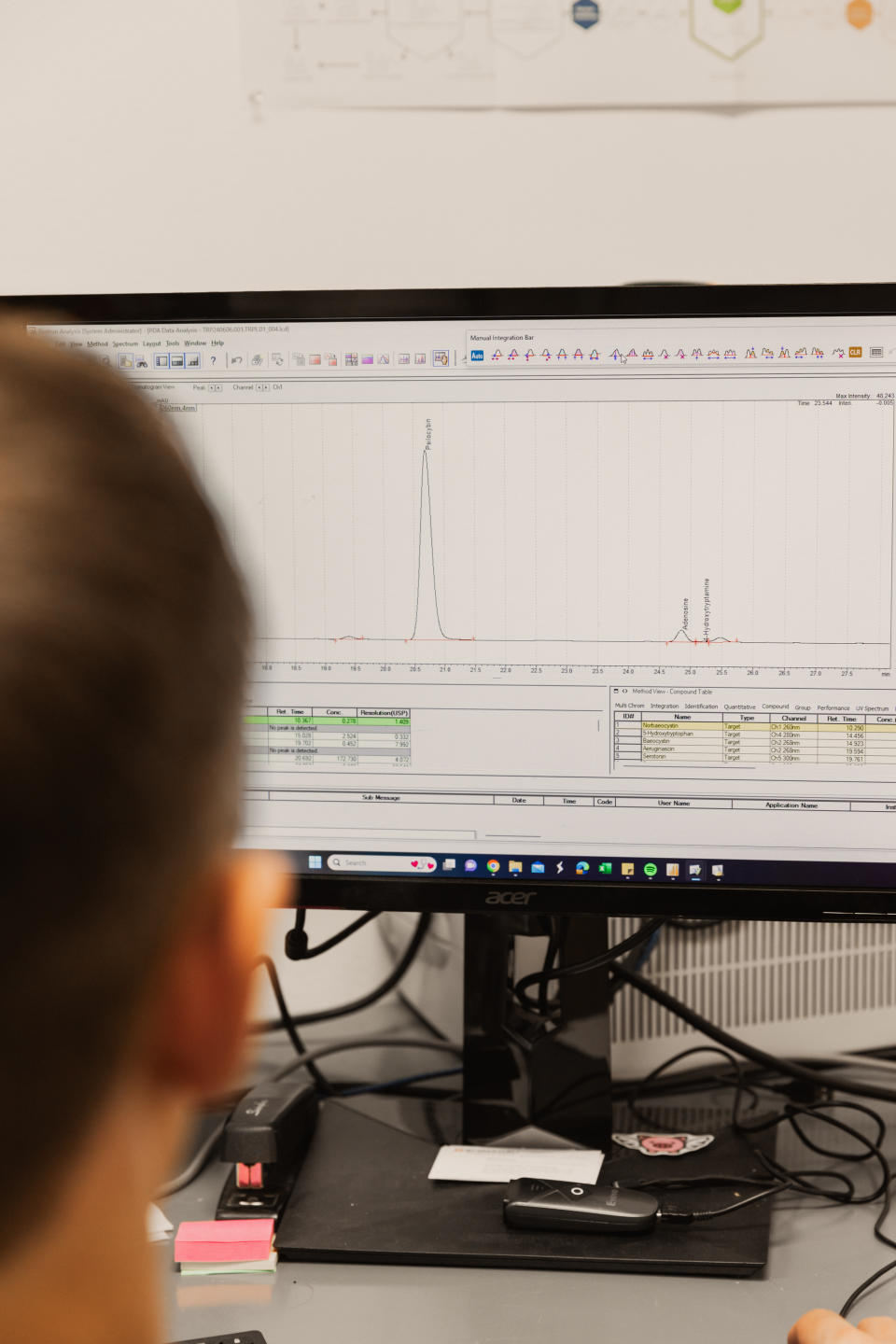

Tryptomics, a Colorado lab, began testing mushroom chocolate bars bought at San Francisco vape shops after a client complained about getting sick. They found some contained 4-AcO-DMT, which can be stronger than psilocybin or contain heavy metals or solvents left behind during production, said Tryptomics founders Caleb King and Christopher Pauli. Companies might be purchasing the chemical - which could be viewed as illegal under federal law - in bulk online.

“Somebody could slap a label on a package saying it contains four grams of mushrooms, and really, it contains a synthetic,” King said. “So it comes down to the consumer having to do their research before they’re going to be consuming anything. And usually that involves testing.”

- - -

A legal mushroom, sort of

Tryptomics also found discrepancies in popular chocolate bars that claim to contain amanita, the distinctive redcap mushroom with white polka dots of “Alice in Wonderland” fame. The mushroom is legal to grow and pick in every state except Louisiana, although it does not grow naturally in much of the country.

Google searches for amanita mushrooms spiked by 114 percent from 2022 to 2023, UCSD’s Leas and co-authors reported in June in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine. The paper warned that the mushroom’s compounds can be highly toxic and fatal at high enough doses.

Investors are spending millions of dollars developing amanita as a mainstream product. Psyched Wellness offers a liquid supplement, Calm, that offers a “light buzz” and is for sale on Amazon and at the upscale Erewhon Market chain in Los Angeles. Psyched Wellness CEO Jeff Stevens said the Canadian company’s panel of scientific experts have certified its amanita extract blend - made from foraged mushrooms - is legal under FDA guidelines.

“We’re a public company,” Stevens said. “We really want to take that mainstream approach.”

The FDA has issued warnings about amanita, noting it is not approved as a food additive, said agency spokeswoman Courtney Rhodes.

“There are documented toxicity concerns, and serious side effects including delirium with sleepiness and coma, among other psychotropic effects,” Rhodes said in a statement.

Websites such as Supreme Mycology in Los Angeles advertise raw amanita mushrooms on Instagram and make health claims including that it “has been proven to treat anxiety and muscular pain and promote restorative sleep.” The website sells teas and chocolates and includes a guide to dosing.

A man who returned a call from a reporter and identified himself as CEO Konstantin Izbekov said he has “never recommended [amanita mushrooms] for internal consumption” without consumers doing proper research. “This mushroom has very big potential, but people need to know how to use it correctly,” he said.

Related Content

Wes Moore, in working to prevent Biden’s fall, is helping his own rise

Supreme Court’s Trump immunity ruling shows risk of Jack Smith’s approach

As his MLB career begins, those who helped lift James Wood cheer him on