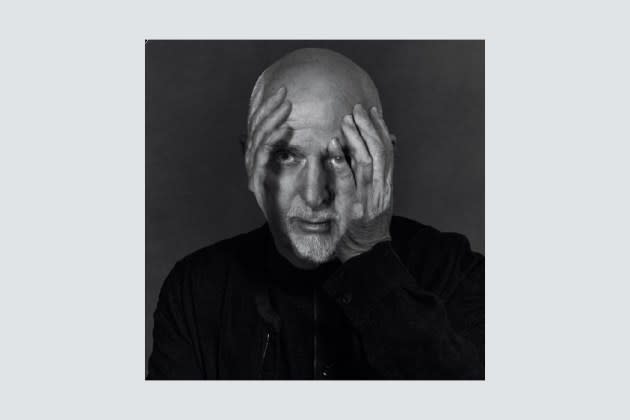

Peter Gabriel’s Welcome Return, ‘i/o,’ Is All About Mankind, Mortality and Multiple Mixes: Album Review

Before talking about the meat of Peter Gabriel’s new album, “i/o,” which stands for “input/output,” it is inevitable that initial discussion will focus on the level of output (or the lack of it) he’s had prior to this year. It’s his first studio album of original songs in 21 years (and only the second in 31 years). For all that gestation time, many things have not changed in these ever-elongating gaps between albums. Like: the returning core band of bassist Tony Levin, guitarist David Rhodes and drummer Manu Katché; the brooding tones that will occasionally give way to a bit of secular gospel or funk; the two-letter album titles (if we don’t count the bifurcating slash that pops up in the middle of this one).

But there are some shifts to consider, once you really go digging in the dirt to find the main concerns of “i/o.” Like: a 73-year-old man is much likelier to make an album focused largely on issues of old age and the ultimate transition than the 52-year-old from whom we last got a collection of fresh material. It’s not quite fully a song cycle, in its meditations on life and death, but it’s just close enough to give another elder statesman’s reflections on those themes from this year — Paul Simon’s “Seven Psalms” — a run for its mortal money. The guy who staged arguably the most mesmerizing arena tour of 2023 isn’t about to lose sight of any big pictures at this stage in his life, especially the really, really big picture.

More from Variety

Elon Musk Biographer Walter Isaacson Thought It Was 'Idiotic' for Billionaire to Buy Twitter

Pokimane Launches Her First Podcast, Promising to Reveal Her 'Most Embarrassing Secrets'

Let’s put the really heavy stuff aside for a second. The biggest difference about this album may lie in the downright newfangled way he’s chosen to release the material, in piecemeal isolation, before giving us the big data dump. Each of the 12 tracks was originally released digitally on one of 2023’s full moons, before being swept up into this year-closing collection. He’s also been releasing two slightly different stereo versions of each number — in a “Bright-Side Mix” executed by Mark “Spike” Stent, and a “Dark-Side Mix” by Tchad Blake. The final three-disc package has those two versions of the album joined by yet a third mix, in Dolby Atmos. Now, a well-known industry blogger devoted part of a column this past week to complaining that Gabriel fumbled by just doing a traditional release of “i/o,” having apparently missed the whole past 12 months of rollout. Is there any less traditional way of releasing an album than doing it bit by bit, in a dozen distinct chunks — each new two-mix two-fer tied not to “new music Friday” or whatever they’re calling it now, but the frigging lunar calendar?

On top of the 36 separate mixes, each song has a corresponding visual representation by a well-known artist, and there are liner notes or track-by-track explanations to cue us into the meaning behind the lyrics, which are sometimes obvious, sometimes quite opaque. If this all sounds like a bit much, you may think of it as homework. If the wealth of variants and supplementary material feels welcome after a two-decade drought, though, the word trove might feel more suitable.

Are the songs treasures? By and large, yes — although I’m not nearly enough of an inveterate audiophile or compulsive A/B tester to really want to compare two or three versions of each of them. There are moments in the overall song selection that aren’t as strong as they could have been; I’m wondering if there was something left on the cutting room floor from these past couple of decades than “Four Kinds of Horses,” a song you will realize is about terrorists only if you read up on it, and which isn’t all that tense or arresting after you do. On his recent, excellent tour, Gabriel made some references between songs to mind-reading or being stuck surveying the world from a chair, and those ideas pop up in a few lyrics here or there, seemingly left over from some point at which this might have been a sci-fi concept album, which it definitely is not now. But the less effective moments on “i/o” are the outlier ones. When Gabriel is being clear and direct, the album can be quite moving, almost in a bring-your-hankies way.

Gabriel often returns to the subject matter of taking stock in the latter part of one’s life. Sometimes these moments are celebrative and scarcely melancholy. To extend the Paul Simon comparison further, a relative banger like this album’s “Olive Tree” is closer to the partying Simon of “You Can Call Me Al” than the elegiac Simon heard on “Seven Psalms” — or closer still, really, to Gabriel’s own “Sledgehammer.” But sometimes he is just trying to break your heart. The penultimate “And Still,” prompted by the passing of the artist’s mother, is a brake-for-sobs stunner, and one of a few numbers that have unusually tender or even naked vocals from Gabriel, a performer whose voice has more often been treated with a kind of mystical fuzz. Anyhow, he typically takes a non-sorrowful view of the end, with the title track erupting in a grand and anthemic chorus as Gabriel half-cheerfully envisions the molecules of his body dispersing on impact with the grave and being joined with “the octopus’ suckers and the buzzards’ wing… Stuff going out, stuff going in.”

Stylistically, there’s not too much coming in nowadays that you can feel certain would not have been a part of a Gabriel album in the early 2000s or early ’90s. So how much difference is there between the three mixes of the album, if nothing about the arrangements in any of them is startlingly different, from one another, or from his very presentable past? Each man and woman will have to make up their own minds about the dual or triplicate “i/o” gambit. Leaving aside the surround mix and just focusing on the two stereo versions, I find myself wavering between two views: First, that having the variations between them be so subtle feels like the setup for a pop quiz that I’m not prepared to take. And, secondarily, that inviting you to decide which mix sounds better adds a bit of fun to the project, and that fun is not a bad thing in the consumption of popular music, especially when it distracts you for a few minutes from, like, thinking about dying, as “i/o” assuredly will.

A quick peek online reveals that, since the album tracks started rolling out last January, no one has come to any particular consensus on which of the two editions rules, though it’s a trainspotter’s delight to debate with each other or oneself about it. Listening to the nice bridge of “Road to Joy,” would you rather hear the “Bright-Side Mix’s” greater emphasis on the weird swirl of strings that kicks in right at 3:25? Or put your vote behind the way the “Dark-Side Mix” tones down the strings a little in favor of thicker bass and more horns? It’s kind of a toss-up, but the “bright” version seems more like what you’d want to hear coming out of a radio or car stereo, and the slightly sparer “dark” edition offers more separation between instruments and is better suited to headphone wearers or rhythm section enthusiasts. (All such generalities being subject to change as you strain to comprehend the differences on a fifth or sixth dual listen.)

In any iteration of the album, the arrangements for the band — who might as well be family at this point — are a big part of his greatness, whether it’s the crescendoing thickness of “Road to Joy” or the way he fleshes out a potentially basic romantic ballad like “This Is Home” as almost a polyrhythmic march. He can get down to true basics, in the no-flab, no-mist look at the ticking clock all of us face that is “Playing for Time,” which owes an admitted debt to Randy Newman at his sparest and most unflinching. Elsewhere, there is the ensemble, to take some edge off, and/or make the blood pump.

Gabriel remains so blissfully distinctive, he kind of defeats some of his own argument about how we maybe shouldn’t take our individuality so seriously, versus accepting our small, limited-edition roles in the cosmos. If there’s a running theme, it’s that the circle of life is nothing to resist, and that all of our life essences — our actual molecules, even — are easily interchangeable… so why not be sanguine about it? Except that you can’t switch him in or out for anyone else in music. Gabriel is, he humbly contends, merely “just a part of everything.” Not on this side of the ground, at least, he isn’t.

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.