'People Don’t Understand How Hard We Work': Life Inside an L.A. Mansion Full of TikTok Influencers

Before they begin a long day of posing for photos and filming TikTok videos, Mariana Morais and Kinsey Wolanski need to exercise—specifically, to shape the backsides that have helped vault them to social-media stardom.

“Damn, girl, your ass looks fat today,” Morais tells Wolanski, a compliment to be sure.

In a garage gym just outside of a sprawling Beverly Hills mansion called the Clubhouse, on a late September day, Morais, Wolanski, and Leah Blefko, one of Wolanski’s two personal assistants, proceed through a lower-body circuit, just a small but necessary part of their careers as influencers.

The Clubhouse is one of several so-called “content houses” established over the past years in Los Angeles. Part production studios, part talent agencies, these houses provide influencers with a lavish backdrop for the abundance of content they make each day and a business model for them to monetize it. A management company rents the house, fills it with comely, twenty-something social-media personalities, and then brokers sponsorship deals on their behalf (for a fee, of course). Then, like a kind of Gen-Z Real World, the residents collectively vie for the most valuable commodity in the influencer economy: people’s attention.

Morais’s workout playlist, featuring EDM remixes of Tom Petty and the All-American Rejects, blares from her parked car as baby-faced influencers trickle in and out the front door. The driveway looks like a luxury car lot, with five BMWs, a Land Rover, a Ford Mustang GT, and two Mercedes-Benzes, including Wolanski’s white convertible. Twenty-two-year-old videographer Keven Zeni interrupts the workout to tell the women he’s on his way to Huntington Beach to shoot a skateboarding video for Monster energy drink. “We’re gonna get so tan on our trip. The sun in the Maldives is so strong!” Wolanski tells him of her own upcoming travels (all expenses paid, one of the many perks of being an influencer).

Wolanski, twenty-four, grew up north of L.A., splitting time between her mother’s suburban home and the farm shared by her father and stepmother. (Her voice has a slight country twang to it.) After high school, she briefly studied to be a nurse, but then went on a backpacking trip throughout Southeast Asia and “realized there’s so much more to life,” she says. Two years later, she moved to Los Angeles to pursue life as a model/entrepreneur/stuntwoman/Internet prankster hybrid. Her big break came last summer, when she stripped down to a black bathing suit and streaked the pitch at the 2019 Champions League final in Madrid. Wolanski spent five hours in a Spanish jail cell, but by the time she was released, her Instagram following had skyrocketed from 320,000 to more than two million. Thus, an influencer was born.

Their workout over, Morais and Wolanski prepare for a busy afternoon of content creation.

Inside, the Clubhouse is a nouveau riche labyrinth, with a pool, home theater, rooftop deck, courtyard, and sculpture garden. Its estimated worth is $29.4 million. Hanging in the foyer is a giant disco-ball chandelier, about six feet in diameter. Filling the wall is, inexplicably, an enormous portrait of George Washington. The kitchen, used for everything but cooking, is littered with Amazon Prime boxes and soiled McDonald’s wrappers.

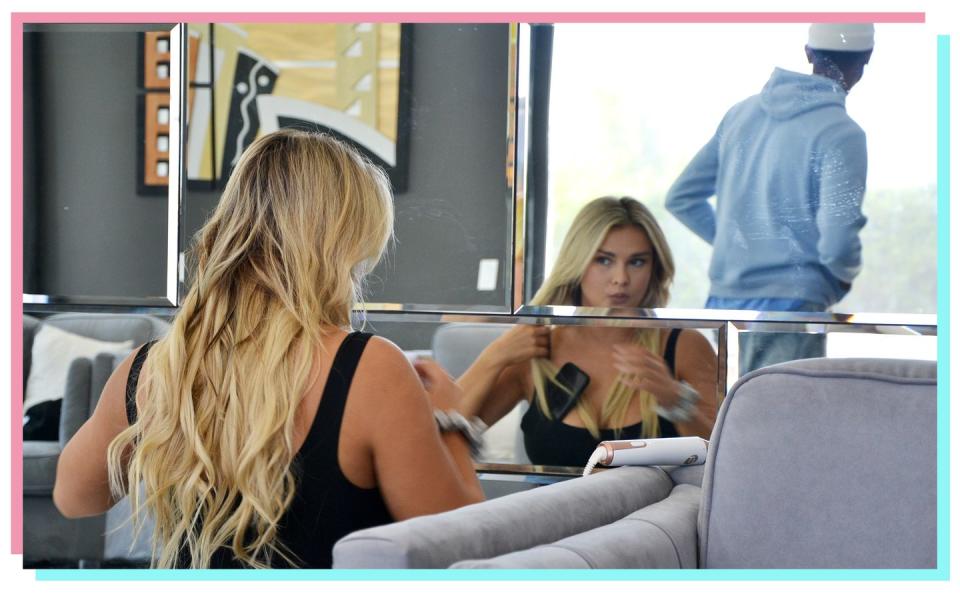

Crouched on her knees, Wolanski does her hair and makeup in the living-room mirror while simultaneously taking a call from a production company, her phone tucked into her black tank top.

“It’s tiring creating content every, single, day,” Wolanski says when the call finishes.

Being an influencer is a never-ending battle to remain relevant. Not only is the appetite for content insatiable, but platforms can emerge overnight, and new stars along with them, forcing influencers into a state of constant brand management.

“You see the Vine kids who fell off when Vine fell off…” Wolanski says, her voice trailing off.

“You have to adapt quickly,” Morais chimes in.

That struggle led them to embrace TikTok, the Beijing-based video-sharing platform that has increased its U.S. usership by nearly 800 percent over the past two and a half years, making it the fastest-growing social-media platform of all time. It’s also been the subject of recent scrutiny from the White House. Both women have more than a million TikTok followers.

The modern influencer archetype arguably began with Paris Hilton, who rose to infamy in the 2000s by way of her social appearances, high-profile relationships, and calculated feuds and friendships with various public figures—an art form then perfected by Hilton’s estranged friend Kim Kardashian. Since Hilton’s reign, social media has democratized the phenomenon, allowing seemingly anyone to rise to the status of celebrity.

Originally from São Paulo, Brazil, Morais moved to Orlando when she was nine. She enrolled at the University of Central Florida to study industrial engineering, but her life took a left turn once she started posting sexy pictures on Instagram. Followers flocked, and so did fashion, beauty, and wellness brands asking Morais to hawk their products. She’s a fitness influencer now, selling diet and exercise plans, such as her At Home Booty Building regimen. “My parents are very traditional, so they don’t understand the influencer life,” she says. But, she clarifies, they do support her.

Unable to find a tripod, Morais attaches her iPhone to the glass patio doors with an adhesive case, and she and Wolanski spend the next hour shimmying for the selfie camera, learning the steps to “Thick,” by DJ Chose, the latest TikTok dance sensation.

TikTok is home to content of all kinds, but it’s best known for its dance videos, in which users replicate and remix routines to hit EDM and hip-hop songs. Aside from the person who creates the trend, it isn’t very original, but it is wildly popular. Wolanski struggles to balance what’s commercially viable with what’s creatively fulfilling. “It’s kinda dumb,” she admits. “You’re not a creator on TikTok, because you’re following other people’s leads.” She’d much rather be creating prank videos, like the one she and Morais made of them doing the highly suggestive “WAP” dance in public (which, coincidentally, is also a popular TikTok dance).

The original TikTok content house was Hype House, founded in December, and the Clubhouse is one of the also-rans to follow in its wake. Morais and Wolanski were among the first group to move into the Clubhouse when it was formed in March to help influencers make content throughout the pandemic. They’ve since moved out in search of a more private living situation, but they’re still represented by the Clubhouse and take advantage of its liberal open-door policy. Now content houses are popping up all over Los Angeles, their proliferation speaking to the seeming power of influencer marketing.

Word of mouth is the most valuable advertising there is, and working with influencers allows brands to achieve it at scale, according to Alexa Tonner, cofounder of Collectively, an influencer marketing agency. Content houses extend the economy of scale even further. Instead of having to broker deals with individual creators, an advertiser can gain access to an entire house full of them.

The economics of influencing are still complex and haphazard. Influencers’ incomes can range anywhere from the low six figures to more than $1 million. Wolanski declined to disclose her income, but with 3.6 million followers on Instagram alone, she’s likely on the higher end. Wolanski’s assistant Blefko, a twenty-seven-year-old beauty queen turned aspiring actress, is an influencer in her own right despite having a fraction of that following (38,500 on Instagram). Clouding the picture further is all the free shit influencers are given—clothes, all-expenses-paid trips, Jeeps.

Ahlyssa Marie, a nineteen-year-old TikTok influencer in an orange hoodie and camo pants, bursts into the room. “Have y’all seen the tripod?” she asks.

“No, we’ve been looking everywhere for it,” Wolanski replies.

People can debate the artistic merit of what influencers produce, but there’s no denying these kids have hustle. After dozens of takes, Morais and Wolanski are finally happy with this twist on the “Thick” dance video, the first of several they’ll make today.

“The hardest part about being an influencer is the credibility of the industry,” Wolanksi laments. “People don’t understand how hard we work. People ask, ‘What do you even do?’ It’s a fun job, but it’s not easy.”

Advertisers certainly view it as credible. Two-thirds of marketers worldwide planned to increase their spending on influencers in 2020, according to an industry survey. Altogether, influencer marketing is expected to be a $15 billion industry in 2022, up from $8 billion in 2019.

Lindsay Brewer, twenty-three, another Clubhouse resident, arrives at the house drinking a Diet Coke from In-N-Out. “Ugh, I can’t believe I ate a Double-Double right before a photo shoot,” she says, though she clarifies it was a Protein Style cheeseburger (wrapped in lettuce, no bun).

The women have hired professional photographer Ian Passmore to take photos of them all afternoon. They change into bikinis, and while he sets up, the subject of conversation turns to dating. “I have a long-term boyfriend, which is tough because you can’t be, ‘Oh, is she dating this guy?’” Brewer says. “My manager always says that’s a good way to grow your following quickly.”

Wolanski currently has “situations” (not relationships) with a couple of guys, one of whom is a professional athlete, though she does not identify him. Her last relationship was with a YouTuber. “After him, I thought I wanted to date a normal guy, a businessman, but then I realized they don’t understand our life,” she says. “We travel a lot, and we have to create content every day. We start working from the moment we wake up.”

Actress-turned-influencer Teala Dunn, twenty-three, joins the crew, and they slip into the outdoor pool. I ask Passmore if he routinely shoots influencers, and he makes a face. “I typically shoot swimsuit models,” he says. “I prefer to do more arty stuff.”

While the women preen in the water, two sisters, Sharlize and Shariah True, film TikTok videos on the nearby patio for their combined 3.3 million followers. Off the patio, Clubhouse member Katie Sigmond (3.8 million followers on TikTok) is on a gray leather sofa, posing for photos in a robe and Calvin Klein underwear.

The Clubhouse residents are almost entirely female, save for one male member, the soft-spoken eighteen-year-old photographer Casius. “I make everyone’s content,” he says. But the Clubhouse also runs Clubhouse for the Boys exclusively for male influencers, a group of whom stop by after a day of shopping. All of them, to a person, wear white sneakers, mostly Chuck Taylors and Air Force 1s. They attended an event for boohooMan, a clothing line, but they didn’t buy anything. The clothes were “beat,” they say.

“It’s boring here. There’s no alcohol,” one of the FTB guys says about the Clubhouse. “Let’s get it.” They depart en masse.

He said girls cant keep up so I asked him to race 🏁🏍🛩 @dmun_aviator

A post shared by Kinsey (@kinsey) on Jul 28, 2020 at 1:31pm PDT

After their photo shoot, Wolanski fiddles with her phone, checking in on her assorted social-media profiles. “We battle every day between chasing engagement versus what we want to produce,” she says, reiterating the classic creative professional’s dilemma. One of Wolanski’s several non-modeling-related talents is as a stuntwoman, as evidenced by a recent video in which she races a biplane on her motorcycle. “I know if I put out a bikini photo, it’s going to get 400,000 likes. But I’d much rather spend my time doing one of my stunt videos.”

Later, Sigmond is in the front room of the house, doing her own version of the “Thick” dance.

“It’s trending,” Wolanski says.

For dinner, Dunn, Brewer, Morais, and Wolanski go to BOA Steakhouse, a West Hollywood joint that’s become the default influencer hangout during the pandemic because of its large outdoor eating space. There, Wolanski details her other creative projects. She has two shows in pre-production, both involving pranks. In December, she plans to launch Kinsey Fit, a fitness-apparel line that has the quality of Lululemon at a fraction of the cost.

All of the women present view influencing not as a profession unto itself but as a means to an end.

Brewer’s passion is race-car driving. She raced sports cars in the Saleen Cup last year, but the 2020 season was suspended. Her manager wants her to drive her go-kart through the streets of Hollywood as a publicity stunt, she says. If she can get arrested doing it, all the better. Dunn is an actress. Her career began when she appeared on the TV spin-off of Ice Cube’s Are We There Yet?, and she has forty acting credits to her name, according to IMDb. Influencing is her side hustle. Morais fancies herself a fitness entrepreneur.

They’re smart to try to forge their separate, self-sustaining paths. For all the attention content houses receive, the business model is flawed.

“Influencers are amazing. They can create videos that immediately dominate the culture. But the houses themselves feel very parasitic and exploitive,” Tonner of the influencer marketing agency says. “I’m not sure it makes any economic sense for anyone—the brands, the house owners, the creators. I’m not sure who is getting the value out of it.”

The check paid, the women put on their face masks; Dunn’s and Brewer’s are from Dior. A crew of paparazzi has assembled outside the restaurant, and the women are showered in flashbulb lights as they leave.

“It’s easy to be an Instagram model,” Wolanski says. “It’s hard doing what I do.”

You Might Also Like