My part in triggering Ghislaine Maxwell’s appeal that could lead to a retrial

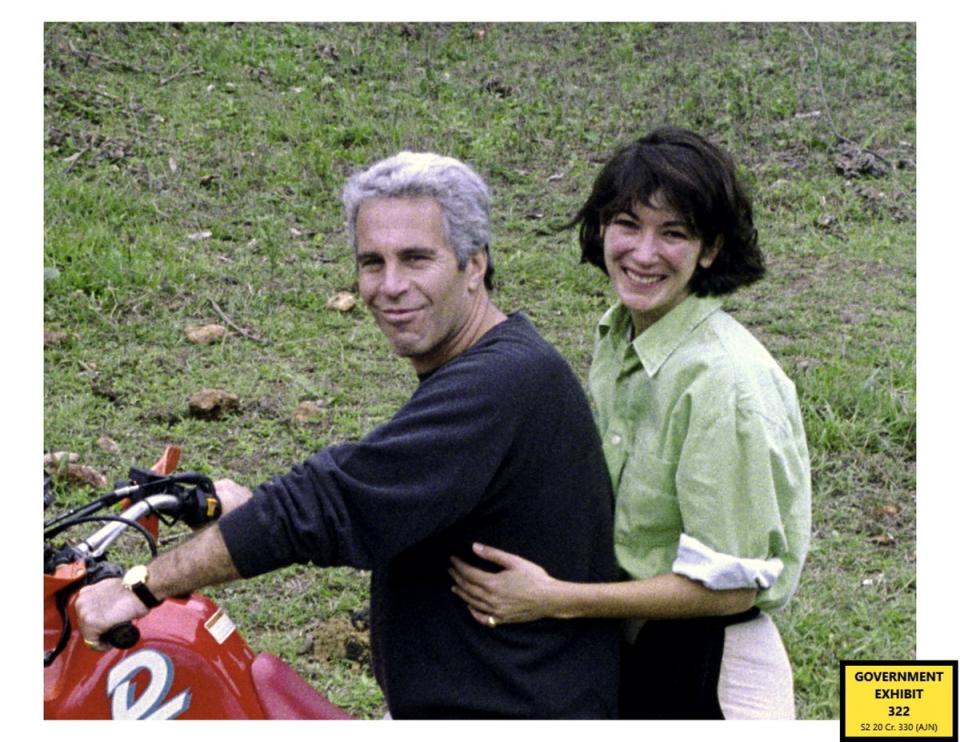

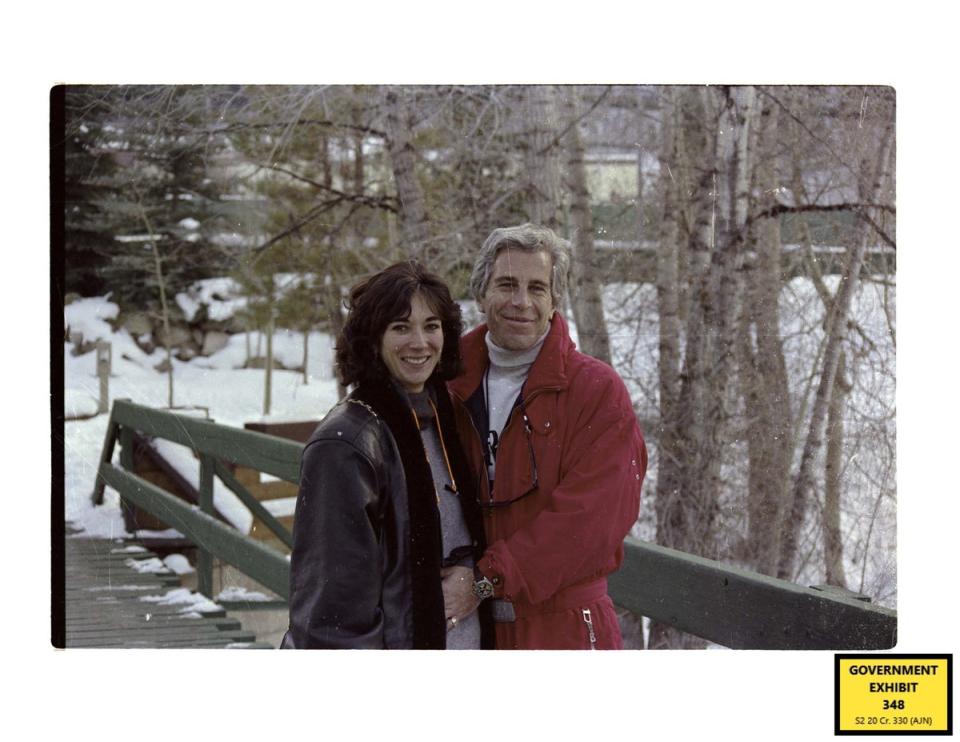

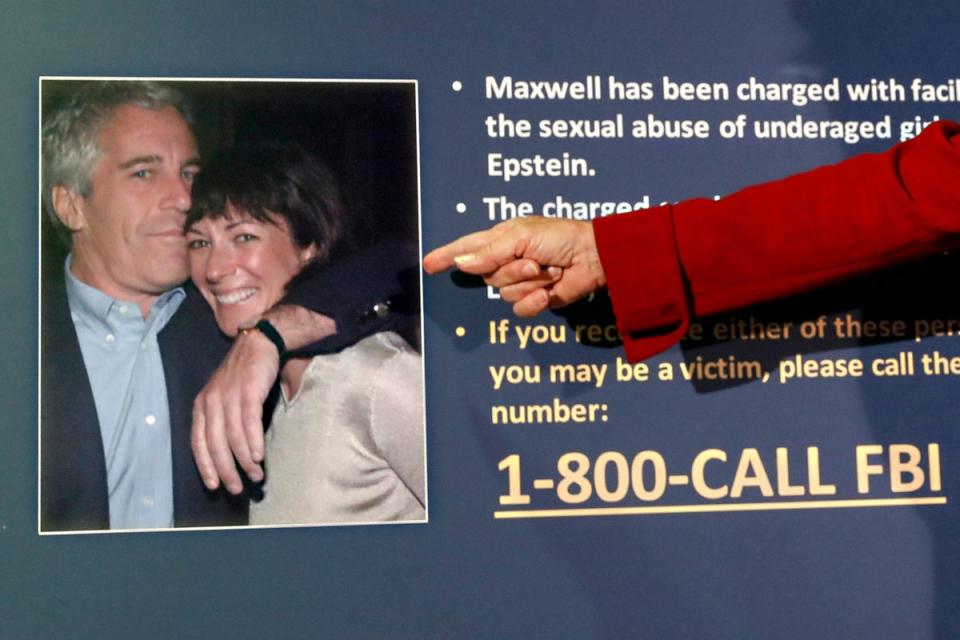

In November and December of 2021, I spent five weeks as one of only four reporters allowed in the main courtroom for the federal sex-trafficking trial of Ghislaine Maxwell, the one-time girlfriend and later assistant to convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein.

That means I sat within a foot or two of her every day for five weeks. One day, she started sketching me on her legal notepad, alongside my press gallery colleague from The Times.

On 30 December, she was convicted on five out of six sex-trafficking charges, which resulted in her being sent to jail for 20 years.

On 12 March, Maxwell will appeal over her conviction and the high-profile case will once again hang in the balance. And one of the bases for the appeal is me.

An interview I published here in The Independent revealed that a juror had failed to disclose, when asked on a written questionnaire, if he had any experience of sexual abuse.

As a result of this interview, it was revealed that two other jurors also failed to disclose similar information to the court, which may, in certain circumstances, have disqualified them depending on the outcome of further questioning by the court and Maxwell’s lawyers.

The question Maxwell’s team wanted to know was: did they deceive the court? It’s a pivotal question and it means that the trial result could be overturned.

My journalism could be the trigger for that. I am of course extremely torn up over this. So let me explain how it came about that my reporting may be the evidence that contributes to a retrial for Ghislaine Maxwell.

This has been a trial that has obsessed me for years, and I will explain why.

In order to be reporting inside the courtroom, I had to queue from around 1am because only the first four in line were permitted entry. On the first day, I arrived at 3am. This was too late, and the one day of the entire trial that I was not inside.

From that day onwards, my latest arrival time was 2am. The earliest I arrived was 11pm the night before, deciding to spend the entire night sitting on cold cement in the depths of the New York City winter, shivering to my bones.

The reason I decided to get up in the middle of the night every night for several weeks to cover this trial is because I believed it would shed light on some of the concepts that we, as a society, still deeply struggle to understand: grooming, child sexual abuse, delayed disclosure and traumatic memory.

And I was right. In many ways, this trial – and I hope, if I’ve done my job, my forthcoming book about the trial, The Lasting Harm – will help contribute to a better, truer and more scientific understanding of how grooming, abuse, disclosure and memory work, and importantly, the damage done to victims of abuse – not only the harm caused by their abusers, but also by the way they are treated by society in its aftermath.

This is true for all traumatic memories but particularly for those of us who have endured organised child abuse, the term used to describe becoming trapped in the grips of a manipulative predator who has a playbook – “playbook” here means a carefully-devised strategy that is repeated and known to work on selected victims – for access to children, and who enacts a repeated pattern of abuse on a number of victims.

In the interests of full disclosure about why I covered the trial, I, myself, am a victim of organised child sexual abuse in a setting that is alarmingly similar – although certainly not involving the same degree of wealth and power – to the trap Jeffrey Epstein and his associates developed over multiple decades. I was then violently sexually assaulted by a stranger in my later teens.

I have been accused many times of being biased because of my history of abuse. To that I say: yes, I am biased. Everybody is, whether we own it or not.

I did not choose to be sexually abused beginning at nine years old, or raped at 15, and the only way I could approach a story with complete neutrality would be by writing about subjects that don’t touch on any of my life experiences. But all journalists have had a great deal of life experiences, and so this is a tall order.

The idea of bias is exactly what I want to write about today, which is why I led with my own. I firmly believe that my experience of abuse should not exclude me from reporting on it.

But this question became much more real – and much more upsetting – when I found myself not only an investigative reporter covering the Maxwell trial, but a key player in its final outcome.

This is how: A chance call. A midnight request.

A night or two after the trial, I was back in England and was sent a link on Instagram for the contact details of one of the jurors. In the US it is allowed – and encouraged – for journalists to interview jurors about their decisions because it is in the public interest for the justice system to be open and transparent.

I believe in this wholeheartedly, and so I asked this juror – Juror 50, Scotty David, who I recognised immediately from the jury box – for an interview. He agreed.

Later that night, we ended up speaking for the better part of five hours – most of the night, London time, and most of the afternoon and evening for him in New York.

I expected that we would discuss his interpretation of the evidence, which we did in great detail. But what I didn’t know is that he would share with me that he, himself, is a victim of child sexual abuse, and that this lived experience helped him understand, and explain to the jury, the nature of traumatic memory.

The insinuation in the interview that his experience helped other jurors understand traumatic memory caused a question to be asked about whether there could be a question of legal bias, if he had intentionally misled the court and tried to get on the jury so he could sway their opinion.

I spoke to Juror 50 for hours. I’ve met him many times. He told me that he walked into that trial believing wholly in the American justice system’s founding principle that everyone is innocent until proven guilty.

He told me he believed Maxwell was innocent. But after hearing the evidence, his belief, and his vote in the jury room, was that she was guilty on all but one of the counts she was charged with. He was also adamant that there was not enough evidence to convict her on the one charge that the jury ultimately dismissed.

As is their right, when my interview was published, Maxwell’s team immediately called for a retrial over the potential issues of bias. I was quickly aware that my interview had resounding consequences.

The court was immediately asked to find Juror 50’s confidential court questionnaire and determine whether he had answered “yes” or “no” to the following question: “Have you or a friend or family member ever been the victim of sexual harassment, sexual abuse or sexual assault? (This includes actual or attempted sexual assault or other unwanted sexual advance, including by a stranger, acquaintance, supervisor, teacher or family member.)”

It transpired that he had ticked “no” to this question, leading to more allegations of bias. However, as someone who knew the legal precedent, I was aware that there is a very strict three-part test for bias in a situation like this.

The first is whether the person intentionally lied on the questionnaire, which, as I said, Juror 50 swore he did not. But even if a person did intentionally lie, to prove bias a judge must also find that the person did so for the main purpose of getting seated on that particular jury. The third test is whether the person was unable to put their experiences aside and impartially decide the case.

Judge Nathan questioned Juror 50 fiercely under oath to determine these issues. She needed to find out, by questioning him, whether the lie was intentional or a mistake and whether he was in fact biased because of his personal experience.

She wrote a resounding judgment saying that she believed his testimony that it was an honest mistake and she said it was clear on the evidence that he examined the case fairly and impartially.

Judge Nathan wrote: “To imply or infer that Juror 50 was biased – simply because he was himself a victim of sexual abuse in a trial related to sexual abuse and sex trafficking, and despite his own credible testimony under the penalty of perjury, establishing that he could be an even-handed and impartial juror – would be tantamount to concluding that an individual with a history of sexual abuse can never serve as a fair and impartial juror in such a trial. That is not the law, nor should it be.”

This is the precedent that is now being challenged on appeal by Maxwell’s team. Of course, appellate judges have the right to overturn the trial judge’s decision – if the three appeal judges decide that Judge Nathan misinterpreted the law on juror bias.

They can overturn her ruling and order a new trial. It is not open to them to vacate the conviction altogether – that is, to set Maxwell free – but only to order that the trial start afresh with a new jury. That’s what’s at stake: can Ghislaine Maxwell find a legal path to freedom?

I felt conflicted. I wanted to get to the truth. I was unprepared for the consequences of my interview. Juror 50 wanted his story of abuse to be told.

Once he disclosed it to me on the record and said he wanted his story told, it was my duty as a journalist to report the truth.

However, of course it was incredibly distressing as an abuse survivor to feel that my reporting of the truth may lead to a retrial.

On the other hand, once again, I always intend to uphold the principles of the law seen through the prism of journalism – and so if something that I report does involve the ordering of a new trial, I respect and honour that decision.

If I had spiked this story out of fear of its consequences, that would have been wrong.

As part of the appeal, I have been asked to testify to the truth of my interview with Juror 50 and its contents. Again, I am happy to do this as I know it is my solemn duty to the court.

After hearing every single day of the evidence, I believe beyond any reasonable doubt that Ghislaine Maxwell committed the sex trafficking crimes for which she has been convicted.

But I also believe, after my own four-year investigation, that it is unjust that she is the only person who has been punished by the law for a sex-trafficking ring that involved countless perpetrators and enablers who continue to walk free.

I accept the jury’s decision that the evidence proves the crimes she herself committed, but justice has not been served if she continues to be the only person punished for a decades-long organised crime ring.

After poring over decades of case law on juror bias, it is my personal view that it is unlikely that any appellate judge could find an error of law in Judge Nathan’s ruling.

If the decision is overturned – which the appellate judges are entitled to do – then I will have to accept that outcome with equanimity and grace – because that is the consequence and value of journalism.

You must be willing to report the truth when you cannot control the outcome, and even if one possible outcome is distressing and turns the present truth on its head.

I believe the jury reached a just verdict. I also believe firmly in every defendant’s right to an appeal, and I am happy to take responsibility for the role I will play in that appeal based on the journalism I published in The Independent.

Justice is never an easy or straightforward path and I never expected to end up in its crosshairs. But appeals are part of how the justice system works, and so what is currently transpiring is what justice looks like.