Opinion: The defining relationship in ‘The Crown’ was never Charles and Diana

Editor’s Note: Louis Staples is a London-based culture writer and editor. His work has appeared in Slate, Vogue, The Guardian, Rolling Stone, Wired and elsewhere. The views expressed here are his own. Read more opinion on CNN.

“You’d be better off trying to modernize Stonehenge!” says an exasperated Cherie Blair. (Or more precisely, the dramatized version of her, played by Lydia Leonard, in the final season of Netflix’s “The Crown.”) Cherie — a known skeptic of the monarchy — is talking to her husband, then-Prime Minister Tony Blair, about the British monarchy.

In episode six, “Ruritania,” Queen Elizabeth II starts to feel threatened by the popularity of Britain’s vibrant new leader — she even experiences a bizarre dream scene, where Blair is crowned “King Tony.” After commissioning a series of focus groups, which produced some bruising results, Elizabeth asks Blair for his ideas on how the Monarchy can “turn things around.”

This scene, set in the private weekly audience between the Queen and the prime minister, is a humbling moment. Recognizing her own vulnerability after a tumultuous few years, Elizabeth begins asking some central questions about the institution she leads. Should the monarchy be more “rational” and “democratic”? Or is that a ridiculous contradiction?

“Ruritania” was a reminder of what has been lacking in the more recent seasons of “The Crown.” The show, which shot to popular acclaim in its early seasons and is now coming to a close, has worked best when incorporating both personal and political dramas, but its increased focus on Charles’ and Diana’s relationship-turned-rivalry disturbed that parity. Moving beyond the princess’s tragic death, the final chapter of “The Crown” has benefitted from rediscovering its more political origins.

Peter Morgan’s Netflix drama has chronicled the first 53 years of Queen Elizabeth’s reign, from her 1952 ascension to 2005. During that time, the changing political landscape has been a constant character. Elizabeth saw many prime ministers come and go, from Winston Churchill (her first) to Harold Wilson, Edward Heath, Margaret Thatcher, John Major and, finally, Blair. The changing role of the prime minister has helped the show’s audience to answer key questions: What challenges was Britain facing at various points in time? How did the royal institution respond — and survive — as the country (and the world) changed?

Depending on the age of individual viewers, “The Crown” has either served as a trip down memory lane, or an education about various scandals and controversies that happened before their time. Everyone might not have known that Churchill’s response to the Great Smog of 1952 very nearly led to his political demise. In season two, we saw how the fallout from the Suez Crisis humiliated Anthony Eden, plus the Queen’s unusually emotional reaction to the assassination of US President John F. Kennedy. In season three, Edward Heath banged his fists on the table as he faced off with miners, who were striking for better pay — a sign of a generation-defining struggle to come.

The politics of “The Crown” intensified in season four. In the first episode, the political and personal collided like never before when Lord Louis Mountbatten, uncle and mentor of Prince Philip, was assassinated by the Irish Republican Army (IRA). Next came the rise of Margaret Thatcher. The UK’s first female prime minister was also one of its most divisive political figures and, even in death, her legacy is still polarizing. Gillian Anderson and Olivia Colman portrayed a tense relationship between Thatcher and Queen Elizabeth. Multiple episodes during that season suggested that there were tensions between the pair on various issues: high unemployment, the 1982 Falklands war and sanctions against apartheid South Africa.

In season five, “The Crown” became overwhelmingly focused on the divorce between Charles and Diana. John Major did appear briefly, but the show became much more personal — and it suffered for it. Not uncoincidentally, this was the first season to be heavily disparaged by critics, who compared the once-prestige drama to a soap opera. In the first part of season six, the emphasis on the personal continued, with Diana’s whirlwind romance to Dodi Fayed and the media rivalry between her and Charles intensifying. Even in the aftermath of Diana’s death, the fierce backlash against the royals from the grieving public was noticeably more muted than it was in Morgan’s 2006 film, “The Queen,” starring Helen Mirren in a role for which she received an Oscar.

Why did “The Crown” lose its political focus? Potential pushback may have influenced its retreat into personal storylines. Every British prime minister since Thatcher is still alive — and, crucially, able to dispute the show’s dramatization of events. (Major described the show as a “barrel-load of nonsense,” after an apparently fictitious plot in which Charles sought his help in possibly attempting to persuade the Queen to abdicate.)

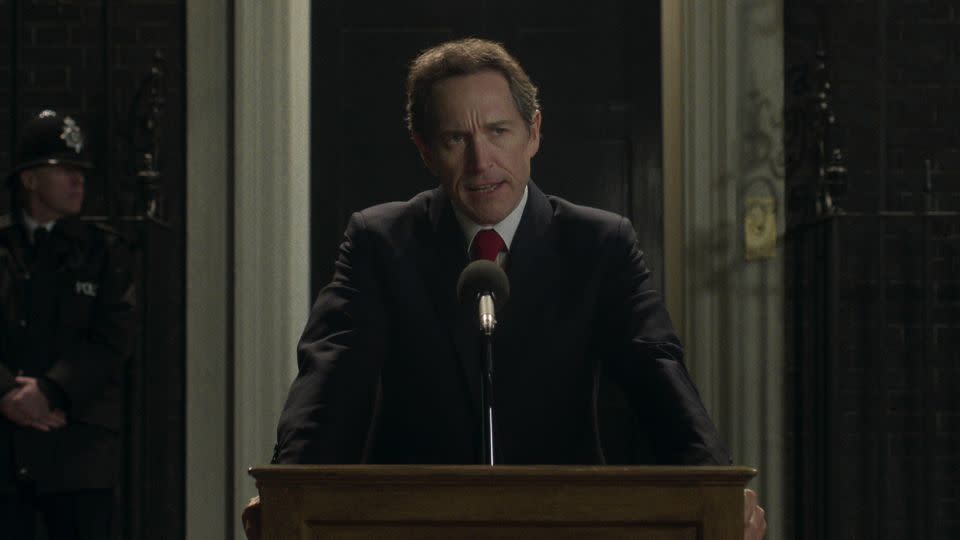

The second part of season six marks a return to a more balanced approach. At the start, we see a confident Blair on the world stage, artfully navigating a military intervention in Syria alongside tensions with the Clinton White House. Next, the unexpected (and controversial) election of President George W. Bush.

It seems like nothing can stop Blair, but we soon discover that he can’t walk on water (as the Queen suspects) when he is heckled and booed while giving a speech to the Women’s Institute. (It turns out that the aspiring modernizer and reformer could still learn a thing or two from Britain’s longest-serving monarch.)

Finally, in the last episode, we are taken to the time of Blair’s greatest misstep: the Iraq War. Protesters line the streets, calling for his arrest, as he arrives for his weekly audience with the Queen. Now, the placards read: “Tony B-liar.” It’s a contrast from when crowds cheered for him on the streets. Suddenly, their positions are reversed: The Queen is once again the constant, watching as another prime minister’s legacy is tainted. Normal service has resumed.

In the early seasons of “The Crown,” the biggest clashes weren’t always between individual family members, but the political tensions that made the royals reconsider their roles as the demands of their subjects changed. Although the final installment doesn’t quite recapture the show’s golden era, it is a welcome reprieve from purely personal melodramas — a return to the political micro-scandals that first made the show interesting.

In “Ruritania,” the Queen ultimately decides against radical modernization. “People don’t want to come to a royal palace and get what they could have at home,” she says. “They want the magic and the mystery.” That, she argues, is their duty. Here, we learn something: Navigating a delicate balance of personal and political has not only been central to “The Crown”’s success as a TV show, but to Queen Elizabeth’s 70 years on the throne — and the survival of the monarchy itself.

Correction: This article has been updated with the correct year of Queen Elizabeth’s ascension.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com