One in a Thousand Winemakers Is Black. These Men Are Working to Close the Industry's Gap.

High-end wine tastings aren’t always the friendliest places if you look young and Black. Standing in a scrum of tasters in San Diego about 20 years ago, I exclaimed over the aromas from my glass of pinot noir. A middle-aged white man with red hair and glasses snapped, “I’m not listening to a thing you have to say.” Little did he know that I was the regional newspaper’s restaurant critic, so people were listening.

Open hostility was rare, but there were plenty of microaggressions at these tastings, like teensy pours and bemused looks. So whenever I spotted another Black person at one of these events, it was a delightful surprise, like running into an old friend on a foreign vacation. It was all the more thrilling if they were on the other side of the table, pouring the wine.

In a $72 billion industry where an estimated one in 1,000 winemakers is Black, just seeing someone who looks like you is a powerful silent affirmation. It says “you belong here” to anyone Black with aspirations in wine. So does knowing that these four Black men, who started pouring wine at a dinner table and then rose to the top echelon of a wine world that’s still extraordinarily white, are influencing what all people drink.

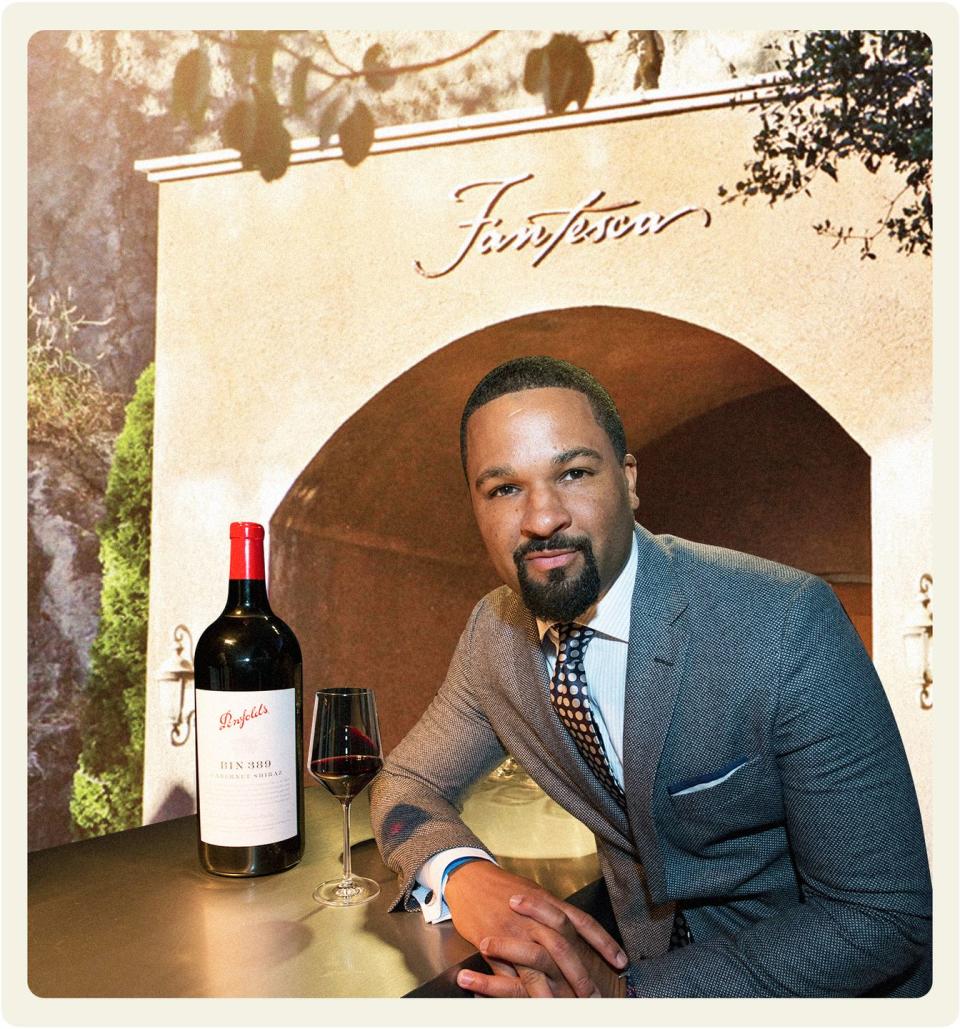

There’s DLynn Proctor, whom you might recognize from the original Somm movie or his recent cameo in Netflix’s Uncorked, which he coproduced. He jetted around as the face of the venerated Australian brand Penfolds; now, at 40, he’s the director of Napa Valley cult winery Fantesca. Just down the road at Heitz Cellar, Carlton McCoy, 35, is president and CEO, leading the iconic cabernet sauvignon producer into a new era. He’s also a high-profile master sommelier, which is like having a double Ph.D. in wine. (McCoy is one of just three Black men in the world to hold that coveted pin, along with Vincent Morrow and Thomas Price.) Then there’s Thatcher Baker-Briggs, a wine prodigy who parlayed stints at elite restaurants, including Tokyo’s Takazawa and Saison in San Francisco, into a private wine consultancy. The 29-year-old procures the rarest Burgundies by Romanée-Conti, Leroy, and Coche-Dury for an international clientele of old money, venture capitalists, tech founders, and athletes.

But the one all the young sommeliers dream of being is André Hueston Mack. As the head sommelier at Thomas Keller’s Per Se in the early 2000s, Mack was nicknamed by coworkers the “black sheep.” “We bumped heads a lot,” says Mack, who’s 47. “I wasn’t allowed to do a lot of shit for whatever reason.” They nixed his idea to wear Prada Chelsea boots instead of lace-ups. They blanched when he described a wine as “bangin’.” The most glaring example, as Mack recalls, was when Riedel stemware, a prestigious Austrian brand, wanted Mack for an ad campaign. Mack was told he “wasn’t the face” of the restaurant group. “But when Black Enterprise came, they were cool with it.”

Mack had already started working on his next act; he left Per Se in 2006 and released his first Oregon wine in 2007. Now, Maison Noir Wines is arguably America’s largest Black-owned wine brand. He laughs about the time he visited a Colorado Springs shop to sell his wine and got followed around like a shoplifter. Today he sells $7 million in Love Drunk rosé (LeBron’s a fan), O.P.P. (Other People’s Pinot Noir), and Bottoms Up riesling blend in nearly every state, plus 22 countries. He’s huge in Sweden, where his leaner, more mineral-driven Oregon wines are a better fit for the Swedish palate than typical American wines. (After Marcus Samuelsson started pouring Maison Noir in his restaurants across Scandinavia, Mack says “it snowballed from there”; now his wines are sold in government-run wine shops.) And his Get Fraîche Cru wine-centric streetwear brand is a six-figure business.

“What I did is create a subculture around the wine culture,” says Mack, who details his journey in his 2019 book, 99 Bottles. “When you thought about wine, you thought about people wearing suits and ascots. I made a subculture of wine by blending wine and street culture.” Now he’s planted his flag near his home in Brooklyn, filling a stretch of asphalt in his neighborhood with components of the next phase of his lifestyle-brand plan: VyneYard wine shop, & Sons ham bar, a market, and soon an artisanal bakery.

Mack’s influences include Sonoma pinot noir maker Mac McDonald of Vision Cellars, whom he calls a father figure, and Randall Grahm of offbeat wine brand Bonny Doon. But he’s pretty much had to be his own mentor. Baker-Briggs, too, is used to being the only one in the room. “I felt I needed to work harder and be smarter than anybody else,” he says. “I don’t think I’m the kind of person that needed the door to be opened. I’m okay with being the person who opened the door.”

But even adults crave role models. Proctor still remembers how impressed he was the first time he saw Jamil Antoine, now a senior executive with Jackson Family Wines, at a wine event. He’s proud to have the same effect on others. “I’m at no mountaintop. I’m at no pinnacle. But does it give [younger folks] something to reach for? Absolutely,” he says.

Inviting more Black folks to join the clubby wine industry is a smart move, considering that Black people have roughly $1.4 trillion in buying power and they’re already drinking plenty of wine. In fact, it was recently announced that Wine Unify, a new nonprofit cofounded by Proctor to celebrate and increase diversity in the wine industry, is one of a few groups sharing in a $1 million diversity investment from Napa Valley Vintners.

For an imagined future of Black American wine culture, McCoy looks not to this country in, say, 2050 but to current-day South Africa. There, winemaking dates back to 1659, and despite apartheid’s fraught history, there’s a thriving wine culture that includes Black-owned and -operated cooperative brands. “All the sommeliers are Black,” he says. “Our community up here is struggling … and they’re far more advanced than we are.” His challenge now for the American wine industry is to create a mental association between Black people and careers in wine, just like the ones that exist for fashion, music, and sports.

Twenty years on, I know that wine tastings have become much more enjoyable, especially since I’m wiser and speak the lingo fluently. But racial profiling of winery guests continues to be a problem. Being the only Black person on staff in a tasting room is no picnic, either. Earlier this year, I walked away from a part-time job I enjoyed at a prestigious tasting room smack dab in the middle of Napa Valley, across from Robert Mondavi. I was good, too, selling $100K in wine in three months and racking up hugs and tips from guests. If not for the ringleader in the tasting room, a good ol’ girl bully who alternated between giving the silent treatment, delivering nasty one-liners, and sabotaging my tastings by hiding my wines or putting out incorrect greeting cards for guests, I would have stayed. Management could never quite figure out what the problem was. I could. Even if you’re talented, to succeed in this field, someone needs to have your back.

It makes me proud to see the viral appeal of Black Girl Magic wines by the McBride Sisters and Brenae Royal managing the iconic Monte Rosso vineyard. Guys like Chris Christensen in Sonoma, James Moss in Napa, and Raymond Smith of Indigené Cellars in Paso Robles are making fantastic wines under the radar. And a leading wine-industry magazine just featured a Black woman on the cover for the first time ever. Sommelier Tahiirah Habibi earned that honor by questioning why she should have to call a master sommelier by the term master. Good question, but why did it take that for one of us to make the cover?

The thaw is only just starting.

Mack thinks that if people get excited about his lists of firsts, so be it. “I’m not caught up in the first,” he says. “Our people sometimes feel like they need to jockey for that position. To be first is, like, whatever. There’s enough room for everybody. I want to be the best.”

We’ll be somewhere when there are so many Black and brown people, and other people of color, doing whatever they want to do in wine—leading brands, running vineyards, crafting blends, and managing tasting rooms—that it doesn’t even merit a story like this one. Then we’ll really have arrived.

You Might Also Like