How one evangelical leader uses the Bible to expose the ‘False White Gospel’

Jim Wallis was a long-haired student activist in the early 1970s who read Marx, marched against the Vietnam War and had little use for evangelical Christianity. But one day he conducted an unusual theological experiment that would change his life.

Wallis and several friends wanted to know how many scriptures in the Bible dealt with issues such as poverty, oppression and justice. So they took a pair of scissors and cut out every biblical verse mentioning the poor.

“When we were done, all of those verses had fallen to the floor — about two thousand verses in total,” Wallis recalled. “We were left with a Bible full of holes.”

Wallis would devote his life to championing those discarded scriptures. He is now one of the most eloquent defenders of a brand of evangelical Christianity that insists that faith is not entirely a private matter — that the church should address racism and public policy issues that affect the poor.

That belief has caused some critics to question Wallis’ evangelical credentials. Some evangelicals see him as a renegade because they are suspicious of his emphasis on social justice and his past work as a spiritual advisor to former President Obama.

Wallis conducts another provocative theological experiment in his latest book, “The False White Gospel: Rejecting Christian Nationalism, Reclaiming True Faith, and Refounding Democracy.” In the book he compares six iconic Biblical texts to White Christian nationalist beliefs. His conclusion: White Christian nationalists also follow a Bible that’s full of holes.

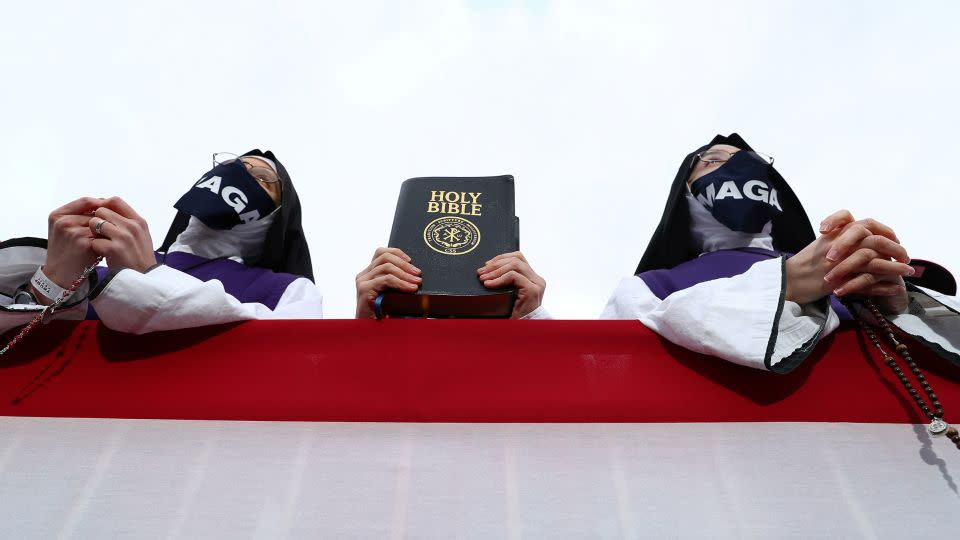

Some may already be tired of the debate over White Christian nationalism, whose followers blend sexism, racism and hostility to non-White immigrants in a quest to create a White Christian America. But Wallis has been warning people about the dangers of White Christian nationalist beliefs long before the term became popular.

He has written numerous books, such as his 2005 New York Times bestseller, “God’s Politics,” that describe how White supremacy has infected Christianity throughout American history. His childhood church in Detroit was racially segregated.

“White Christian nationalism has cut out of their Bibles all of the Scriptures that lead faith to justice,” Wallis writes in a passage that recounts his youthful episode with the scissors. “When is the last time you heard a white Christian nationalist MAGA pastor talk about justice from the pulpit — justice for the poor, for the immigrants, for those being discriminated against? The only words that relate to ‘justice’ are predictions of punishment for all those who oppose their political agenda.”

Wallis’ new book is an altar call, a history lesson and a savvy guide for social justice activists. He writes that every successful movement must distinguish between those who must be defeated versus those who can be persuaded, and that Jesus has become “a victim of identity theft in America.”

He also celebrates the power of “proximity,” a process whereby empathy and compassion bloom between different groups when they have genuine, intimate encounters with one another. He says the political environment in the US is now so bitter in part because there is little proximity.

“The white people who are most against immigrants are those who have never lived anywhere near them, and the American citizens most open to immigrants are those who have encounters with them in their communities,” he writes.

Wallis, who speaks in a gravelly preacher’s baritone, is currently the director of the Center on Faith and Justice at Georgetown University in Washington. He recently spoke to CNN, and his remarks were edited for brevity and clarity.

You write that White Christian nationalism is not new, and that it’s a form of heresy. Why do you consider it to be such a danger?

The name spells the problem. You have the most inclusive and inviting, welcoming vision in the history of the world for all people and it becomes White. You’ve got “Christian,” but it doesn’t mean service, sacrifice and love. It means control and domination. And then it’s nationalist. In the Great Commission, Jesus tells his followers to go into all the nations, making disciples and teaching them to observe whatever I have commanded you. [White] nationalists just don’t fit into that.

This [White Christian nationalism] is an old idea from the Doctrine of Discovery, which says that this country was for people who were White Americans. And now that idea is having a real comeback. A lot of people are drawn to the idea of America as a special nation created for White Americans.

What’s the difference between patriotism — believing that the US is an exceptional country — and White Christian nationalism?

To love your country and love so many things about your country is a good and healthy thing. Pete Seeger’s “This Land Is Your Land” is a lovely patriotic song. However, American exceptionalism is wrong. It’s not biblical. After I finished the book, [former President] Donald Trump began selling his own Bible and taking the proceeds himself [Trump is reportedly just taking a portion of the proceeds]. When you have “God bless the USA” on a Bible cover, that’s idolatrous, that’s a worship of a nation. Idolatry is just false worship. People talk about White evangelicals and White Christianity. The problem with those phrases is the word that dominates the phrase is not evangelical or Christianity, it’s White. So whiteness is idolatry.

Is it unrealistic to expect many pastors and church leaders to speak out against White Christian nationalism now? Church attendance is declining. Pastors are just grateful for any warm bodies that come into the sanctuary. A lot of pastors don’t want to alienate people in their congregation. What do you tell them?

I talk to pastors and they’re getting death threats from congregants and people in the community. So there is a great fear out there. So how do we deal with faith and fear?

At the beginning of the book, I tell a story about speaking at Candler (Emory University’s Candler School of Theology in Atlanta, Georgia) and Black pastors were pleading with White Southern preachers to tell the truth about race. These young White pastors basically agreed with everything the Black pastors were saying. Most of them probably had a Black Lives Matter sign in the front yard. But they were worried about the risks. A female pastor said if I lose my parsonage, how do I take care of my family? Another said I’m afraid of the emails I’m going to get. I may lose my pension. Too many members might leave. One young guy said my senior pastor tells me when I’m preaching to remember the demographics of my donors.

So I said to them this is a Bonhoeffer moment [Dietrich Bonhoeffer was a German pastor who was executed by the Nazis for his role in trying to overthrow Adolf Hitler. He could have found refuge outside of Germany but chose to return to Germany despite the personal danger]. So yes, there’s a price to be paid. We don’t know what it is. But the other thing that happens is if members leave, others will come. And some of them are younger people who are going to be drawn to truth-telling.

You write about compassion for immigrants at the Southern border. What’s wrong, though, with people wanting secure borders? That doesn’t automatically mean you hate immigrants, does it?

Most of the people I know who want a just and fair immigration policy, which we haven’t had for a long time, believe we ought to have secure borders. That’s not a problem. I met a car driver last night who drove me back to Pittsburgh. And one of the first things he said to me was that he doesn’t like the way Trump talks about immigrants now. He probably believes in a secure border. And so do I. But the way he talks about immigrants, the way he ‘others’ people, is a theological issue.

Let’s take the Parable of the Good Samaritan. A lawyer comes to Jesus and says, What can I do to inherit eternal life? Who is my neighbor? Who am I obligated to? And Jesus tells the story of the Good Samaritan, but to the Judeans to whom he was talking to they didn’t think there were any good Samaritans. They thought they were dangerous and worshippers of false idols. The Samaritan was “othered,” like the other immigrants and refugees and ‘those people’ who are supposedly going to replace us in this multiracial democracy.

That story, for example, gets right to the immigrant problem. It gets right to the great replacement theory [A belief originating in White supremacist circles that non-White immigrants, Blacks, Jews and others want to replace native-born White Americans in the electorate]. How we treat those labeled as the ‘other’ is clear in the Biblical narrative.

Some defenders of White Christian nationalism say the term is mostly used as a smear against conservative Christians who just want to defend the role of religion in American public life. Your response?

No, that’s wrong. I want to defend the role of religion in public life. I’ve done that my whole life. The separation of church and state, which I believe in, does not require the segregation of moral and religious values from public life. Dr. [Martin Luther] King didn’t believe that he got to win because he was a Christian in a Judeo-Christian country. He knew he had to win the debate for the common good. He didn’t think he should win because he’s a Christian. They want White Christians to have inordinate power. King said he wanted to remind the church that we are not the master of the state, nor the servant of the state. We are the conscience of the state. We should be conscience of the state but not the master. We shouldn’t be implementing our views through force of law.

What happens to the US if White Christian nationalists gain control of the federal and state governments, and the courts?

Mark Twain reminded us that history doesn’t repeat, but it does rhyme. I was at a dinner last night with a very good scholar who spent some time in Latin America and elsewhere. She brought up the 1930s, and she said that Hitler was elected as chancellor; it wasn’t through tanks and guns. What they’re doing in Hungary and Turkey and elsewhere is that they win elections, and then they slowly change things. They become virtual dictatorships. That’s what we’re facing. Trump has not been apologetic about saying what he’s going to the judiciary, to the civil service, to the Justice Department itself, even to the legislature. This [White Christian nationalism] is a threat to democracy as we know it.

There is an intriguing statement in the book that I can’t get out of my head. You write that change never comes by majorities — it’s countercultural minorities who change things. Can you elaborate?

Most people don’t even know that King didn’t have majority support in Black churches during the civil rights movement. There were a whole lot of people who were very cautious and careful. But the people who were on the streets and engaging in non-violent direct action, they were always a minority. It’s always a minority who changes things, and the majority goes along with it in the end. It’s always a minority who figures out what kind of messaging, what kind of action, what kind of demonstration is necessary to reveal what’s true and then the majority says, Oh, I see your point. Let’s do that.

You also write that there are some people that need to be defeated and others that need to be persuaded. How do you make that distinction?

Most people, most religious folks, they just want to be bridge builders and persuade. But what’s just as important is that we have to defeat some people. If I didn’t think there were persuadable people, I wouldn’t have written the book. I don’t think we can persuade some captive people. Jesus said, you’ll know the truth and the truth will set you free. But the opposite of truth is not just lying, it’s captivity. A whole lot of good people are captive to these notions of White supremacy and White minority rule. They would never say that. But that’s what they’re really hoping for. So they’re captive. Then there are political religious power brokers who are just going for power by any means necessary. And those people have to be defeated at the ballot box.

John Blake is a Senior Writer at CNN and the author of “More Than I Imagined: What a Black Man Discovered About the White Mother He Never Knew.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com