"We Don't Know What to Do For All These Mothers"

My mother, the nurse, blinks herself awake at 5 a.m.

She reads her Our Daily Bread devotional, a prayer book by the Christian ministry of the same name. Then she thanks God for waking her up once again, on this cloudy morning. Sixty-three years, God has been waking her up each day.

There are so many people who went to bed last night and didn’t get to see today, she thinks.

After her quiet devotion, she drinks Nescafé with a little cream and two Equals, shuffling around the modern, airy kitchen in the house she just bought, watching the morning news and weather: overcast with a high of 45. The death rate in New York City is surging by the day, the TV says, and increasingly overwhelmed and burnt-out medical teams are crying for help.

Today, she adds two boiled eggs to her morning nourishment. That thing inside of her that tells her to bring the babies into the world, and to keep them healthy—she feels it extra strong these days. Maybe stronger than ever. It’s going to be a long day.

She eats the eggs.

My mother is the OB-GYN head nurse at Lincoln Medical Center, a public hospital in the South Bronx. There are 362 beds at Lincoln. Its web site boasts that the hospital’s level 1 trauma center is “the busiest in the northeast region.”

She dreamed of being a nurse from when she was five years old, growing up in Benin City, Nigeria, population 1.5 million, near the Atlantic coast. She loved the white uniforms and the blue and red pens she saw sticking out of the towering nurses’ chest pockets when she went to the doctor. She wanted to wear that uniform.

In 1970, her father was in a motorcycle accident and broke his leg. My mother stayed with him in the hospital. “I told my mom, ‘Don’t worry. I’ll do everything,’” she says. “The whole time he was there, I volunteered to be the one to change his bedpan and sleepover. Everything. I felt good that I was able to be there to help him.”

She was 14.

Around 6:30, mom begins her drive down Bruckner Boulevard in her black Toyota Highlander from the Shorehaven neighborhood, where she lives, to Lincoln.

She used to have to leave earlier, because of all the school buses on the road. The streets are quiet now.

When bad things happen, humans respond in all kinds of ways. We bring a meal, we send a card. We donate money. Maybe we even volunteer our time. Sometimes we ignore the bad things, convinced that our own lives demand too much of us. But mostly, we want to help, and we feel a little better when we do.

We can say, “I did that.”

Some people? Like my mom? They make it their job. There are a lot of ways to make a living, and my mother chose to take care of sick people and new mothers. She gets that same rush of satisfaction we all get when we do a good deed. She just gets it all the time.

It felt good that I was able to be there to help him.

In normal times, when she arrives at Lincoln to start her shift, the lobby on East 149th Street is crowded—people waiting to be picked up, people drinking coffee, people coming and going. Guards casually monitoring things, giving people directions. There are homeless people, even, catching some warmth.

Now? The lobby is as desolate as the city around it that, before the pandemic descended, never slept. Within the familiar burnt-orange and sky-blue walls, the active noise of anticipation and concern that normally vibrates throughout the place has been replaced by waves of silence. The waiting area chairs, more than fifty of them, have all been removed. The yawning space now only contains the security guard’s post. The guest check-in cubicle at the main entrance to the building is now a makeshift screening station stocked with surgical masks and an oversized clear bottle of hand sanitizer for incoming patients, who must show documents proving that they have an appointment.

Once she’s on 5B: Maternity—her unit—she enters her windowless office, changes to her white lab coat, washes her hands, and puts on gloves and a surgical mask, which she will wear for her entire shift. This is a new precaution.

“Everything is changing,” she says of the new required procedure.

The maternity unit has not yet been escalated to N95 respirators—the tighter-fitting mask with a higher filtration of airborne particles. Until now, the cases that have come through her unit have been primarily quarantine cases, including a Hispanic woman in her late-twenties. The woman had only held her newborn baby for a few seconds before she showed two signs of the virus: high fever and shortness of breath.

Immediately after her delivery, her blood was drawn. She now lays in 5B awaiting the results, separated from her baby and her family.

A vague fear of death permeates most other units of the hospital—of any hospital. Not Maternity. The maternity unit is about life. As an OB-GYN nurse, my mother is accustomed to—and finds joy in—welcoming new life. She is always optimistic.

Except that it’s getting harder right now.

“I feel so sad when I think about anything hurting the mothers or babies,” my mom says. We’re talking using FaceTime—me in my apartment in Manhattan, her in her house, after her shift. “Can you imagine if the mother is affected—or even passes? Then, who’s going to raise the child? Every baby needs their mother. I’m praying and trusting God that nothing bad will happen. I don’t even want to think about it.”

Outside the new mother's isolation room is a three-drawer rolling cabinet with a set of personal protective equipment, or PPEs, in each drawer: a yellow isolation gown, surgical mask, plastic face-shields and gloves. Yellow isolation gowns, used for low- to moderate-risk scenarios, have been designated for quarantine cases.

The blue isolation gowns are for positive cases. They have an added layer of protection.

“My name is Patience Omokha,” my mother says, entering the woman’s sterile room. The air smells strongly of Clorox. “I’m the head nurse for the day shift, and I’m doing my rounds. How are you feeling this morning?”

The petite woman wears a bluish-gray patient gown, and a white bed sheet swallows her lower body. A clear water pitcher rests on the bedside table. Next to the bed is a portable blood-pressure machine.

“Oh, I’m okay,” she says, somberly. She is fair-skinned, which makes her brown hair striking. A blue surgical mask covers her nose and mouth.

My mom takes her vitals: temperature, pulse and respiration. Her temp is still 101.

The patient sizes up my mom: a 5-foot-6, shapely frame covered by a yellow isolation gown, her sweet oval face and dark brown eyes partially showing behind her surgical mask and the plastic face-shield wrapped around her head.

“Do you understand everything that’s going on now?” my mom asks. “Do you know why we put you in this private room?”

“Yes.” The woman pauses. A blank expression fills her face before she adds, “I think so.”

“What do you understand is going on?”

“They said I can’t see my baby because of this virus thing,” says the woman. “I have to stay here until the test comes back.”

The tests are due back in one to three days, typical for new mothers suspected of being infected with the virus. Until the results are in, she won’t see her baby boy.

“How are you feeling about that?” my mom asks.

“I know this is for my own good,” she says. “And for my baby, too.”

Last week, two mothers who tested positive for COVID-19 were admitted under the same protocol. Like them, their newborns were also placed in isolation until test results return for both the mothers and babies.

“We don’t know what to do yet for all these mothers,” my mom says. “All we can continue to do is be there for them and make them feel comfortable.”

New York is an epicenter for COVID-19, with over 44,000 confirmed cases as of Friday. Hospitals are adapting on the fly, and healthcare workers are scared for their safety—especially with limited PPE supplies.

In 5B, nurses complained about not having any blue isolation gowns left, so my mother set up a meeting with the associate director of the hospital’s Department of Infectious Control to reassure her team that the yellow isolation gowns were just as effective for quarantine cases as the blue isolation gowns were for positive cases. The hospital will dispatch blue isolation gowns, when necessary, to the units that need them the most, the associate director told them.

“Some of my nurses are scared for themselves and their families,” my mother says. One of her nurses recently tested positive for the virus and is on her tenth day of quarantine. “I go in those rooms because I have to, it’s my job. I hope to always lead by example, even when I’m concerned about getting exposed myself.”

Hearing my mother say that frightened me, as I consider the possibility that she could herself be infected with the virus. The fear grew even more when she later texted me: “Oh my goodness, the results for the patient just came back and she is positive.”

The new mother she'd spoken to has COVID-19.

As I read her text, I wondered, was my mother more afraid about contracting the virus, or was she more scared that a newborn baby might grow up without a mother?

I think she is fearless because growing up, she had to be.

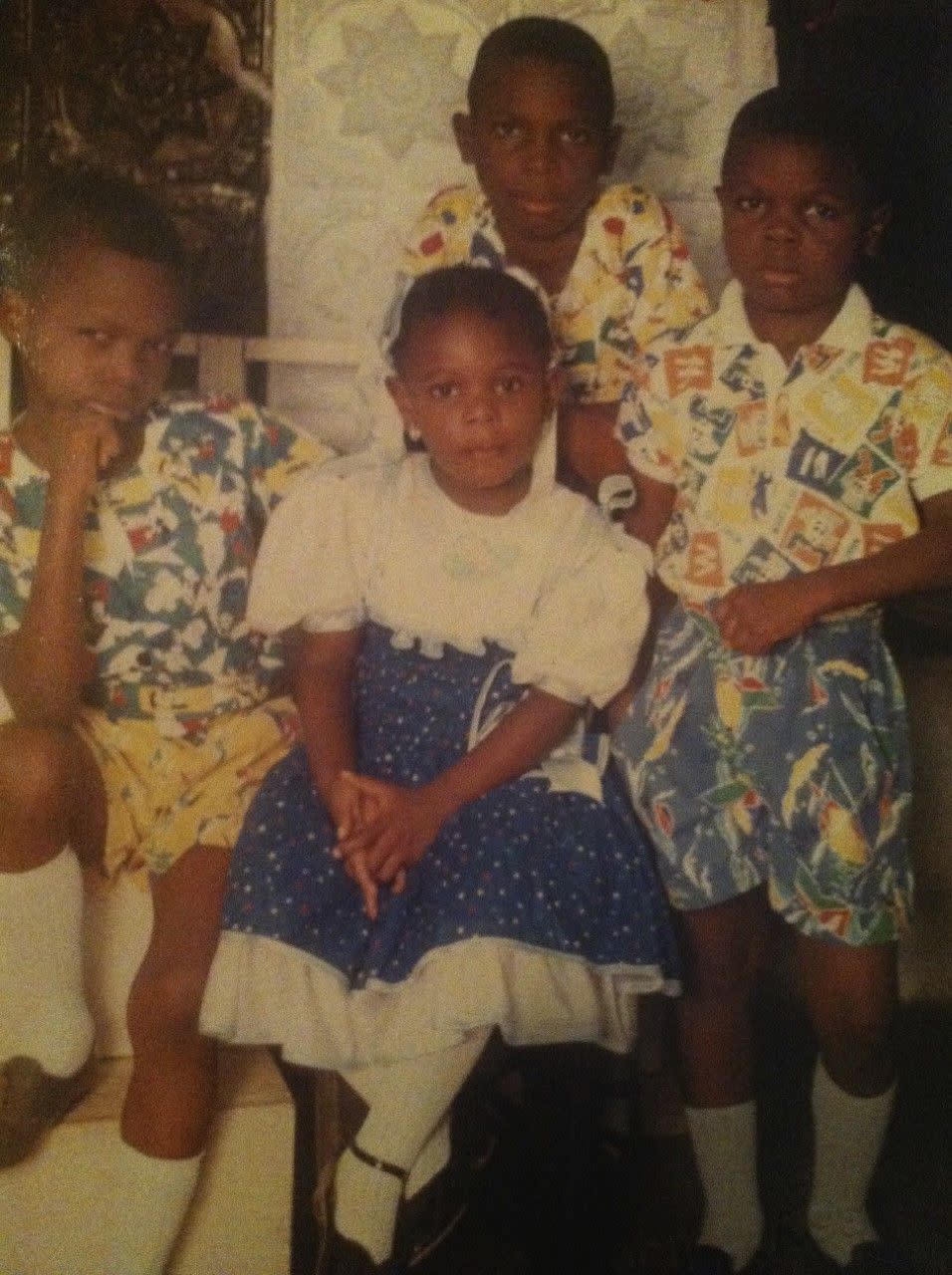

She grew up middle-class in Nigeria, one of six siblings. Education was optional for women. A domestic lifestyle, and marrying into an affluent family, was the goal.

Not for Patience.

Getting to that white uniform would prove difficult with mounting school expenses and family challenges, like the seasonal income from her family’s storefront business. But then my grandmother, who was uneducated, joined mom’s fight for her dream. She sold all her special-occasion ankara and lace clothes—high-quality, sought-after fabrics then—to help raise enough money to get mom’s schooling started in Ibadan, the third most populous city in Nigeria. The balance would later come from loans.

“That kind of sacrifice, I’ll never forget it,” she tells me, our FaceTime conversation growing long.

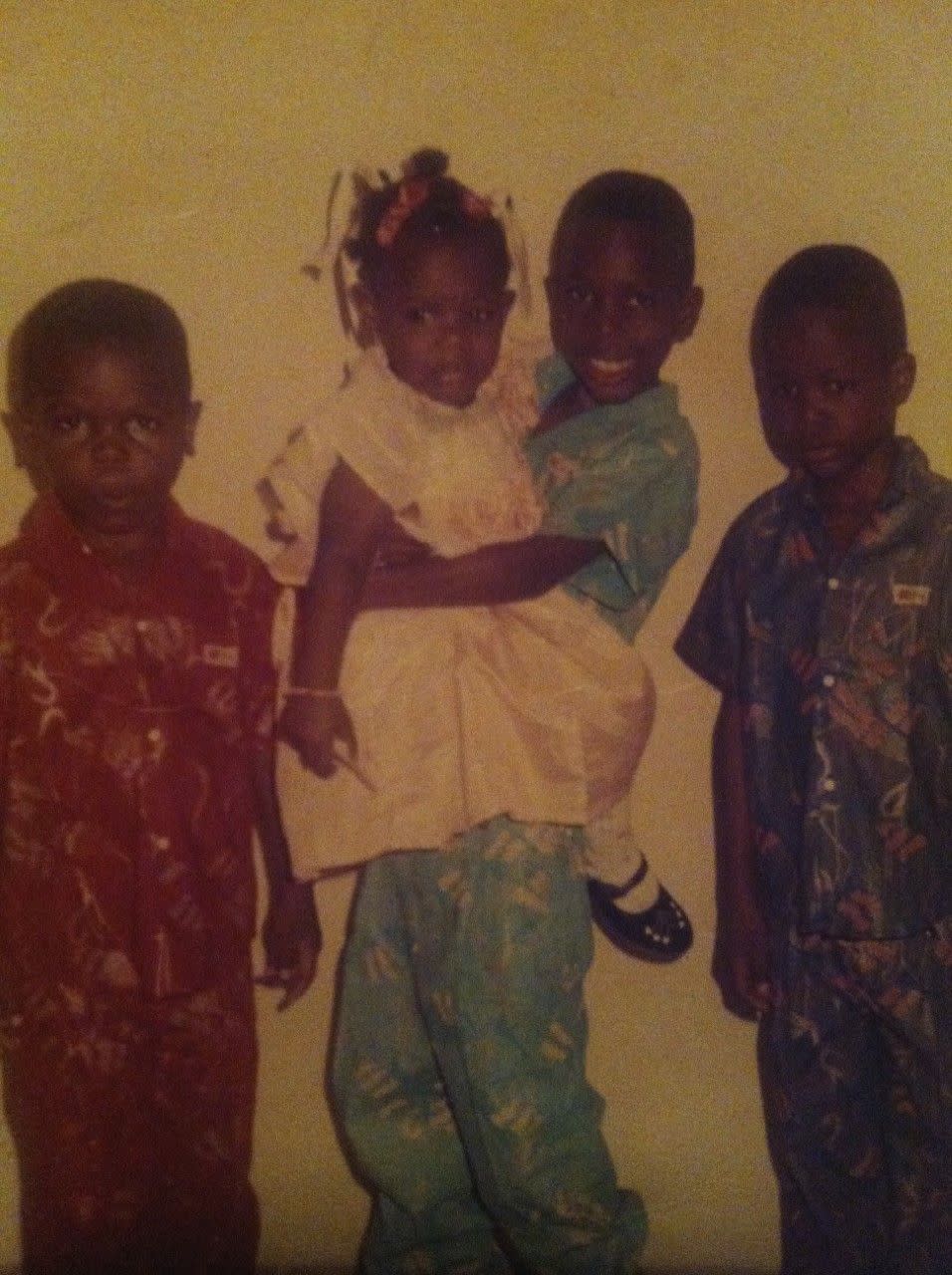

My brothers and I joined mom in America in 1995, when I was seven. We lived in a modest two-bedroom white row-house on Intervale Avenue, in the South Bronx. One morning when I was about nine, I noticed a giddiness in her step.

Already dressed in her multi-colored uniform, hair grease dripped from her primped Jheri curls onto her top. She went between sternly telling us we only had minutes before we had to leave the house and rummaging through the hall closet in search of snow boots. She looked at her thin gold wristwatch—she was running late. The number 2 train at Freeman Street ran on a schedule. If she missed the next one, she would lose a few minutes before the next train arrived.

I remember just noticing her in this haste, and seeing her, really seeing her, perhaps for the first time: That was the morning I realized mom was a nurse, and not just mom.

On March 18, Lincoln imposed a new policy on 5B: Mothers are no longer able to have the support of friends, family members, or doulas in the delivery rooms.*

Nurses, like my mother, are all they have.

“Father, sister, partner or grandmother—nobody can come for the delivery or visitation,” she says.

Typically, on the day of discharge for a mother and new baby, the family would bring a change of clothes, car seat and balloons to the mother’s room—all manner of happy things to mark the joyous moment. No more. Even car seats aren't allowed inside the hospital. Upon discharge, a nurse must escort them out of the building and off the premises to their pickup vehicle—where fathers, sisters, partners and grandmothers await to finally meet their newest family member.

“Every day there’s something new,” my mom says. “Everyone is overwhelmed.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced many other changes at the hospital, which has more than twenty clinics. Each clinic normally attends to over 100 people at any given time, but now throughout the day, at the different intervals—10 a.m. to 12 p.m., 1 p.m. to 3 p.m., and on and on—they only allow ten to fifteen people at a time.

Nurses are also being called to help understaffed units. My mother now splits her time between maternity and the main medical floor, with patients who have pre-conditions like hypertension, diabetes and asthma.

Today is day 13 since I last saw or hugged my mom.

What we would normally do today, maybe: She might take me on a Costco run, or she would drop off a homecooked meal and groceries at my apartment. We’d get our nails done at the corner of East 76th Street and Second Avenue before crossing the street to Blossom Brows for our threading appointment. We’d catch up on everything, often having the same conversations as last time, garnished with more details.

Just before the outbreak, I was also in the middle of helping her decorate her new home.

Because non-patients are not allowed at her hospital right now, and I don’t want to endanger her by going to her home, I interviewed her for this story over FaceTime. The usual excitement for her daily routine was drowned with balmy concern.

Still, we had our laughs. I told her I needed details: “What colors are the lobby walls?” I asked her.

“The color of the walls!” she said, as she munched on her dinner. “I never notice these things!” Then she squeezed her face and pressed her lids shut, “I’d say—it’s—uh, orange, but not orange-orange. But, it’s orange, though. And, also like a light blue too.”

Moments like these and our regular check-ins tame the disconcerting feelings.

She has always been tenacious. She walks into that hospital every day ready to tackle uncertainties—scary uncertainties—and lead her team with courage and love. I miss her, but I am prouder to be her daughter. Her drive for what she loves has challenged and inspired me throughout my life. To see her meet this challenge encourages me to remain fearless, especially now.

“This is what I love to do,” she tells me. “I need to be there for my team more now. I don’t want them to get burnt out. This virus is scary for all of us because no one knows what’s coming.”

My mother has been planning to retire next year. But now I see her so eager to be there each day, like the more dangerous things become for people, and the more she can help them—let’s just say I’m not planning her retirement party just yet.

“Why did I become a nurse in the first place? This is why,” she tells me. “When someone tells me ‘Thank you,’ or, when they hug me—when they used to, anyway—it made me feel so happy to be doing what I’m doing. Now I’m always thinking about how I can help more people, especially those mothers. They are scared and lonely when they are quarantined and waiting for their results.”

When my mother texted me about her patient testing positive, a second text immediately followed.

“Pray for me!!!!!”

Editor's Note: A policy change was announced this week allowing one person into delivery rooms. However, visitors were still not allowed at Lincoln Medical Center at the time of publication.

You Might Also Like