Nimble tech firms must adapt as promised self-driving revolution hits speed bumps

By Alexandria Sage

SAN FRANCISCO (Reuters) - When Silicon Valley startup Phantom Auto was formed in 2017, it was one of many software suppliers hitching their fortunes to self-driving cars, confident that fleets of robotaxis would be using their technology within a few years.

But with delays in the mass deployment of autonomous vehicles, Phantom is now finding new customers off the road - on the sidewalk with delivery robots.

Phantom is not alone. Faced with the harsh reality that an autonomous future is further away than originally promised by global automakers and tech companies like General Motors Co <GM.N>, Uber Technologies Inc <UBER.N> and many others, smaller companies in the self-driving ecosystem are now pivoting to alternate uses for their technology. Some are turning to delivery robots, while others are helping deploy autonomous vehicles for farms, construction sites or airports.

Robotaxis are still considered the industry's "humongous opportunity," in the words of Phantom co-founder Elliot Katz, but shifting to creative new ways to deploy the auxiliary technologies allows for immediate revenue during the long slog before autonomous vehicles hit the roads en masse.

The widescale deployment of robotaxis, once pegged by industry analysts to be a $2 trillion industry by 2030, is now seen as further away due to a variety of hurdles, among them cost, complexity and unresolved legal and regulatory concerns.

Meanwhile, more modest rollouts of self-driving vehicles are coming sooner in limited areas with defined borders.

The shift in expectations is driving players large and small to rethink strategies and re-evaluate financial risk. On Monday, automotive technology supplier Aptiv PLC <APTV.N> said it has agreed to puts its self-driving vehicle unit in to a joint venture with South Korean automaker Hyundai Motor Co<005380.KS>. Hyundai will contribute $2 billion to the venture. Rival automakers Ford Motor Co <F.N> and Volkswagen AG <VOWG_p.DE> in July agreed to combine autonomous vehicle operations.

In Phantom's case, its remote operations technology, which allows a human operator miles away from an autonomous car to take over control when the car is confused, can be used for less safety-critical tasks.

Postmates, a San Francisco-based goods delivery company, will use Phantom's technology inside fleets of over a hundred sidewalk robots as they navigate sidewalks and crosswalks to deliver lunches, snacks, or other goods to customers, beginning next year.

"We had to figure out where is autonomous technology deployable today," Katz told Reuters. "It's about handpicking the right opportunity for the immediate term, medium term and long term."

Egil Juliussen, research director for automotive technology at IHS Markit, said that using the same technology for non-automotive applications, like robots, is a simpler path to market that can still tap the startups' artificial intelligence technology.

French autonomous shuttle maker and operator Navya SA <NAVYA.PA> threw out its financial targets in July and unveiled a new strategy of selling its technology to others.

The catalyst was the continued uncertainty over regulation that jeopardized anticipated fleet orders by customers last year, Chief Operating Officer Jerome Rigaud told Reuters. That led to missed 2018 revenue projections and the removal of Navya's founder and CEO.

Navya still plans to test its self-driving shuttles without a safety driver by early next year, but it now sees new opportunities in areas where regulation is simpler: hauling goods at airports, industrial sites and construction areas at slow speeds in limited areas, and in agriculture, Rigaud said.

MORE MONEY, PLEASE

Evangelos Simoudis, managing director of Silicon Valley venture capital firm Synapse Partners, which invests in autonomous technology startups, said VCs recognize that full self-driving will take much more money, as well as time, to recoup the 10x return on their investments of $5 million to $50 million - amounts that are typical in the sector.

In the interim, smaller companies are on the line.

"If they have flexibility they may pivot and go to something adjacent or radical in order to survive, but nonetheless there will be a period of significant change," Simoudis said. "There will be quite a high mortality rate."

The sweet spot for companies searching for alternative ways to use self-driving technology is software related to simulation, data annotation and data management, Simoudis said.

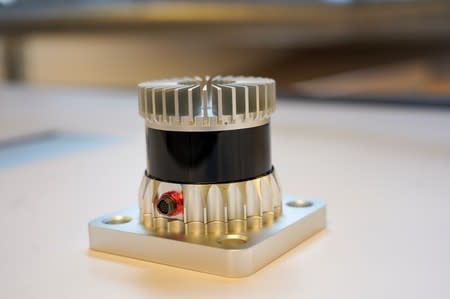

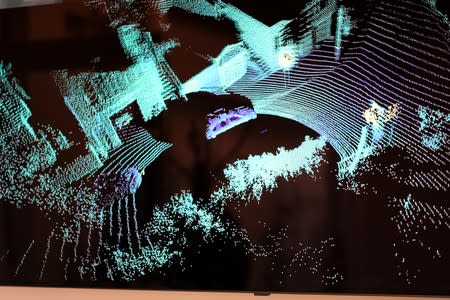

Companies making software are better positioned to pivot than those doing hardware, experts agree. There has already been some consolidation in the crowded field of lidar, a key hardware component using laser light pulses to help vehicles "see," after some companies have struggled to raise new funds. Digital mapping is another area ripe for consolidation, Simoudis said.

Automakers and others have snatched up these startups in recent years, including Strobe Lidar and Princeton Lightwave, which were acquired in 2017 by General Motors and Argo AI, respectively. Argo AI is majority-owned by Ford and VW. Earlier this year, self-driving startup Aurora bought Blackmore Lidar.

Last month, food delivery company DoorDash bought startup Scotty Labs, a competitor to Phantom also involved in the remote control of autonomous vehicles. The loss of Scotty's main customer, Voyage - which operates small fleets of self-driving vehicles in closed residential communities - and difficulties in raising funds led to its sale, two sources told Reuters.

Executives at Ouster, a startup whose lidar technology is also found inside Postmates' robots, said it was a conscious decision from the start to avoid focusing exclusively on automotive lidar.

Instead of diversifying, too many companies have focused on the "pot of gold at the end of the rainbow," said Raffi Mardirosian, Ouster's vice president of corporate development, making them vulnerable to setbacks in the broad deployment of autonomous vehicles.

"If you're in these investor meetings like I am, they're saying 'Show me the contracts. Show me the monthly revenue,'" said Mardirosian. "The fact that we can point to that is something that will help us stay in business."

(Reporting by Alexandria Sage in San Francisco; Editing by Matthew Lewis and Chizu Nomiyama)