How Modi’s hometown has been transformed to ‘pump up the cult’ of India’s prime minister

For one of the best-known political leaders in the world, Narendra Modi’s backstory is remarkably shrouded in myth and mystery. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Vadnagar, the Indian prime minister’s hometown in the western state of Gujarat.

Modi has spent more than 30 years in public life – the last 10 as the domineering leader of a country of some 1.4 billion people – but most of what is known about his early years is a collection of contentious and sometimes contradictory stories that he and his admirers have told.

Speak with his relatives and old acquaintances in Vadnagar and they talk animatedly about the young man they once knew and their association with him, but there is barely any detail. They relate anecdotes about Modi the man that seem to echo the public persona Modi has assiduously crafted over the years, the story that has become the standard narrative of his approved biographies and public recollection.

Vadnagar, about 90km south of state capital Gandhinagar, was a small and nondescript town up until a decade ago when Modi won his first election as prime minister, and it suddenly shot to national prominence. Like most Indian small towns it had scant public infrastructure, even though Modi had been chief minister of Gujarat for 13 years.

Today, as Modi is inaugurated for a rare third consecutive term as prime minister, Vadnagar is a bustling township with better roads, a decent railway station, music festivals and an active archaeological research site digging out its Buddhist history.

The chief attractions, though, are the places associated with Vadnagar’s most famous son. There is the temple Modi prayed in, the school he went to, the crocodile-infested Sharmistha lake where he supposedly swam as a boy and, of course, the now famous railway platform where he is said to have sold tea with his father.

Vadnagar was put on Unesco’s tentative world heritage sites list in 2022 and the substantial facelift it has received since, Modi’s critics say, is designed to assign it a place in India’s history as the birthplace of a great leader, not unlike Sabarmati Ashram less than 60 miles away which has come to be forever associated with the father of the nation, Mohandas Gandhi.

“Modi transformed this city,” says Jasuben Asaram, who has lived all her 70 years in the city.

“Everything changed after Modi became prime minister. You see that lake?” she says, pointing at Sarmishtha, now sporting a redeveloped embankment. “It did not look like this earlier. It was rather dirty, with no place to sit. Now people come to boat here.”

Modi first took power in Gujarat in late 2001, handpicked by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s national leadership to steady its flailing state government.

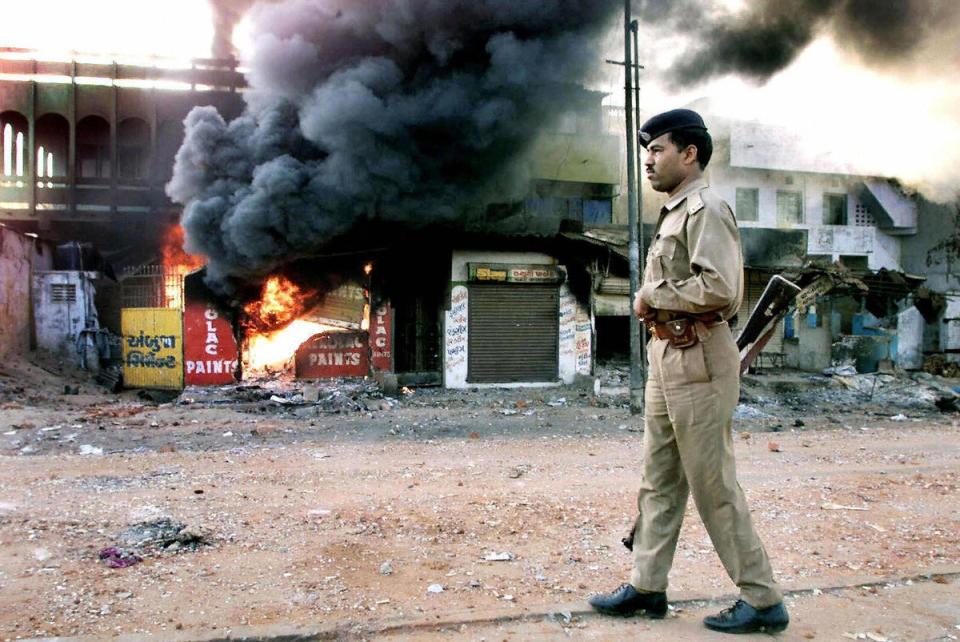

Barely a few months into his rule, Gujarat was convulsed by religious riots that began with a train carriage full of Hindus being burned and turned into a pogrom against the state’s Muslim minority that saw nearly 2,000 people killed, dozens of women raped and tens of thousands displaced.

In 2023, Modi’s federal government banned a BBC documentary examining his suspected role in the pogrom, and just a few weeks later tax officials were dispatched to raid the British broadcaster’s offices in Delhi and Mumbai.

But back in 2002, Modi rode the Hindu majoritarian wave unleashed by the Gujarat riots to win his first election as chief minister – a post he would keep until moving to Delhi as prime minister 12 years later. His party has continued to dominate elections in the state ever since.

In his years of ruling Gujarat, Modi, through thinly disguised sectarian rhetoric and deft marketing campaigns, projected an image of a leader who was at once “Hindu Hriday Samrat”, meaning the leader of Hindu hearts, and a champion of economic development.

He pushed the idea of a “Gujarat model” of economic development which, while he was vying to become prime minister, he promised to bring to the rest of the country.

This is the image of Modi that endures in Vadnagar, and Gujarat generally, although the townsfolk are reluctant to acknowledge the anti-Muslim animus inherent in it.

That enduring reputation makes it no surprise that Modi’s party felt assured of a clean sweep in Gujarat at the elections just gone. In the end they won all but one of the state’s 26 parliamentary seats, despite spending much of their campaigning energy elsewhere.

“Since 2014 Modi has improved the city a lot. He brought a hospital, a better railway station and helped develop business. Now it feels like there is someone looking after us. It did not feel that way earlier,” says Asaram.

Alpaben Patel, 42, who works in a cow shed, echoes the sentiment. “The city changed after he came to power. He does everything well. Everyone likes Modi ji, even children,” she says, using an honorific for him. “He is the pride of our village.”

Asked if he is prejudiced against Muslims, she responds: “No, no. There is no oppression of Muslims under Modi ji.” After a pause, she adds: “But he holds everyone accountable. There is no injustice anymore.”

In the past two months of election campaigning, Modi has made a number of speeches vilifying the country’s 200 million Muslims, drawing widespread criticism and even a slap on the wrist from the country’s increasingly docile election watchdog.

The opposition alliance, he thundered at a campaign rally in Gujarat on 7 May, “is asking Muslims to ‘vote jihad’”.

“I hope you all know what the meaning of jihad is and against whom it is waged,” he said.

While Modi’s BJP fell well short of the majority mark of 272 seats, winning only 240 in its own right, a coalition of his allies together won 293 seats, some 61 ahead of the opposition INDIA alliance led by the Congress Party.

Modi has never tried to hide his communalism, says Apoorvanand, a Delhi University professor and political commentator who goes by one name, pointing in particular to his rhetoric around the Gujarat riots.

But Modi’s admirers in Vadnagar either feign ignorance about his divisive politics or deny the accusations altogether. “I don’t agree at all,” says Somabhai Modi, the prime minister’s older brother.

“I will tell you a story,” he continues. “There is a Muslim village near ours and a boy from there, named Abbas Ramsada, studied in Vadnagar. His father died and it affected his studies. Narendra brought him home and he lived with us. Our mother would cook for all of us and we would eat together.”

Somabhai Modi lives in an old people’s home that he runs in Vadnagar. That Modi’s close relatives live ordinary lives is uncharacteristic of Indian politicians, and burnishes his image as a man of humble upbringing who wants nothing for himself or his relatives, devoting his efforts solely to serving his country.

Modi does not have an immediate family of his own. His marriage, like much of his personal life, is shrouded in secrecy.

He is reported to have married Jashodaben Chimanlal when he was 18 and she was 17. Three years into the marriage, Modi left and threw himself into his work as a campaigner for the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the ideological mothership of Hindu nationalist organisations in the country including the BJP.

In his nomination papers for the 2014 election, however, Modi mentioned that he was still married. Jashodaben, now a retired schoolteacher in her 70s, lives in near obscurity with her relatives near Vadnagar.

“I have no familial ties,” Modi said in 2014. “Who would I try to benefit through corruption?”

In a speech five years later, the prime minister said he devoted “every moment of my time, every pore of my body” to his countrymen.

This also explains why it has been hard for Modi’s critics to make even serious allegations of corruption and crony capitalism stick.

Be it the Rafale fighter jet deal or corporate funding of his party through the electoral bonds scheme, which the Supreme Court has recently declared unconstitutional, Modi has escaped every scandal under his government largely unblemished.

“You have to try to understand this through Indian mass psychology,” explains Apoorvanand. “We often regard a fellow honest who doesn’t have a family. Because if you talk to a common person in India and ask them about Narendra Modi, they will ask you: ‘For whom will he do corruption?’

“So if he makes policies which benefit corporates or if he makes policies which take away the natural resources of India, which are public resources, and give them to two or three capitalists, it’s not seen as corruption because people don’t understand the relationship between politics and the corporate world and why it should be seen as corruption.”

To his admirers, not least in Vadnagar, Modi can do no wrong.

“One of his brothers lives in an old age home. If Modi ji wanted, he could have taken and put him in a big house in a big town. But Modi ji is not corrupt,” says Praful Baria, 42.

Indeed, the contrast in the lifestyles of the Modi brothers is hard to miss.

While the prime minister is always immaculately dressed and groomed and wears designer clothing in public, his brother wears a simple white cotton kurta pyjama. While Narendra Modi basks in the privileges and luxuries of his job, Somabhai Modi spends his days in a dimly lit, sparsely furnished office.

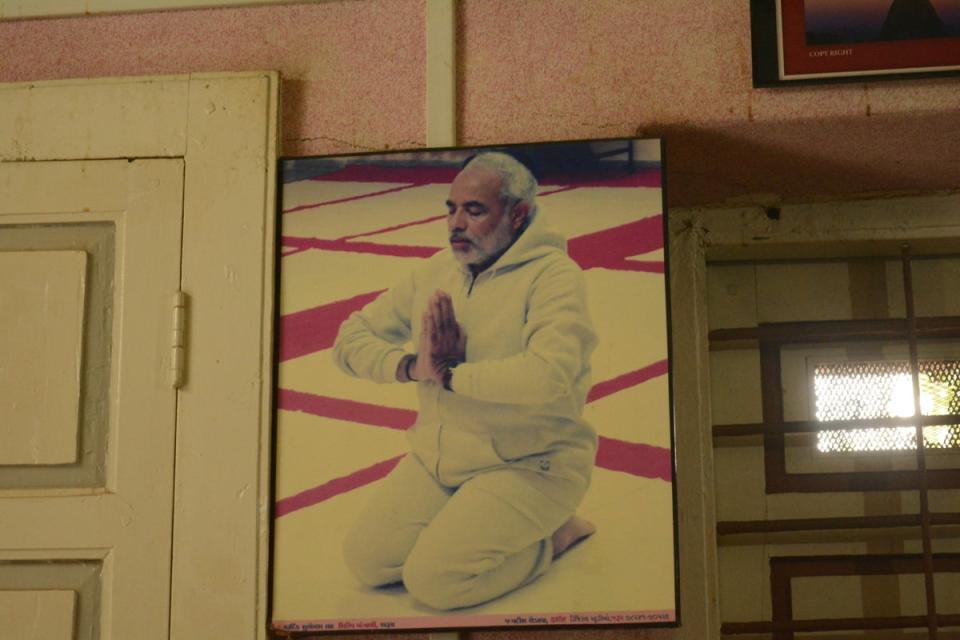

Hanging on one side of the wall behind his chair is a framed portrait of their father and on the other a picture of a young Modi kneeling in virasana, the hero-yoga pose.

When he is asked if his picture could be taken, he politely declines. “Click this instead,” he says, pointing to his brother’s photo on the wall.

“Narendra is honest,” Somabhai says, defending his brother against allegations of corruption and crony capitalism.

“In Narendra’s heart India is number one,” he says. “People of India are number two. And for the development of the people he works to develop industry here. Monied men like Ambani and Adani can help establish more industries which will help bring employment.”

He is referring to Mukesh Ambani and Gautam Adani, billionaire industrialists from Gujarat who are considered close to Modi.

Narendra Damodardas Modi was born to Damodardas Mulchand Modi, a Gujarati tea seller, and Hiraben Modi on 17 September 1950, the third of their six children. While the prime minister made widely publicised visits to his mother until her death in late 2022, he is rarely seen with his siblings.

Somabhai Modi, for one, hasn’t met his brother since the Gujarat assembly election, which was conducted in late 2022. “Narendra always moved ahead with a lot of clarity. He was like that when he was in school and he is like that now,” he says.

“He had good relations with everybody and took everyone along,” he says, echoing Modi’s popular first-term slogan “Sabka Saath Sabka Vikas”, meaning “Together with all, development for all”.

Modi himself never lets pass an opportunity to talk about his early years and strike a contrast with the more privileged lives of his rivals, many of them scions of political dynasties like Rahul Gandhi, the face of the main opposition Congress party.

“I was born in a very poor family. I used to sell tea in a railway coach as a child. My mother used to wash utensils and do lowly household work in the houses of others to earn a livelihood,” he said in a 2015 interview with Time magazine.

“I have seen poverty very closely. I have lived in poverty. My entire childhood was steeped in poverty.”

His old acquaintances in Vadnagar vouch for Modi’s story of a hard childhood but provide few specifics. “My mother and Modi ji’s mother would wash utensils together during Diwali,” Patel says.

Manakaji Gagaljee Darbar, a frail man in his late seventies, is a star in his locality due to his childhood association with the prime minister.

Darbar is visibly uncomfortable at the prospect of speaking with a reporter and seems to hide behind a pillar of a flour mill where he is employed by a distant relative of the prime minister for 6,000 rupees (£57) per month. A small crowd of his neighbours cheer Darbar on, encouraging him to talk.

“When we were children, he would give fellow students a tight one under the ear,” Darbar begins, referring to Modi. “He would hit them playfully, [he was] a bit naughty, I mean,” he says.

Darbar doesn’t remember how long they were friends before Modi “left him for Delhi”, but he knew the future prime minister until they were about 15.

“If he liked anything of mine, he would just keep it,” he says, eliciting a roar of laughter from the crowd of mostly middle-aged men. “So, if anything of mine was missing, I would immediately know that he had taken it. The next day I would go asking for it, ‘Hey! Give it back.’”

“This is the only side I know of him from when we were children. Naughty and wild,” says Darbar. “But he always wanted to do something. That was his constant thought and drive.”

Darbar says he worked with Modi at his father’s tea stall in Vadnagar’s railway station. “When a train arrived, Modi and I would sell water and tea together,” he says.

“We never thought that he would one day become prime minister of the country. But he was definitely more intelligent than us.”

Though the story of a young Modi selling tea at Vadnagar railway station has been called into question, it has become such an integral element of his background that a massive replica tea kettle has been installed at Vadnagar’s revamped station with a note explaining its relevance.

The installation is part of a project to turn Vadnagar into a tourist destination centred on Modi.

An “art gallery” has been set up on the banks of the Sharmishtha lake where a miniature likeness of the prime minister serving tea is the main attraction.

Modi’s school is getting a makeover as a “centre of inspiration” for students from across India. In this Prerana centre, two students each of grades 9th to 12th from elsewhere in the country will be enrolled for five days a year.

“The aim of Prerana is to inspire students of all districts of the country from a place where the inspirational journey” of Modi started, declares the website of the project under the ministries of education and culture.

The Archaeological Survey of India is also in town, digging up the region’s links to Buddhism.

There are 11 protected archeological sites and monuments in Vadnagar, most notable of which is a ruin of a Buddhist monastery excavated in 2008-09 when Modi was the state’s chief minister.

All this is happening because “Mr Modi is citizen number one of this country”, says Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, journalist and author of several books on Modi and his party.

He contrasts Modi’s approach to securing his legacy to that of predecessors Manmohan Singh and Atal Bihari Vajpayee.

“Neither of those leaders believed in the principle of ‘I, the man’. Mr Modi loves the first person singular. He loves the word Modi. Every noun and pronoun he likes about himself.”

Vajpayee, the first prime minister from BJP, “was not so self-obsessed a leader,” he says, “neither was Dr Manmohan Singh”.

“Mr Modi has promoted and pumped up his cult image. And Vadnagar is a part of that.”