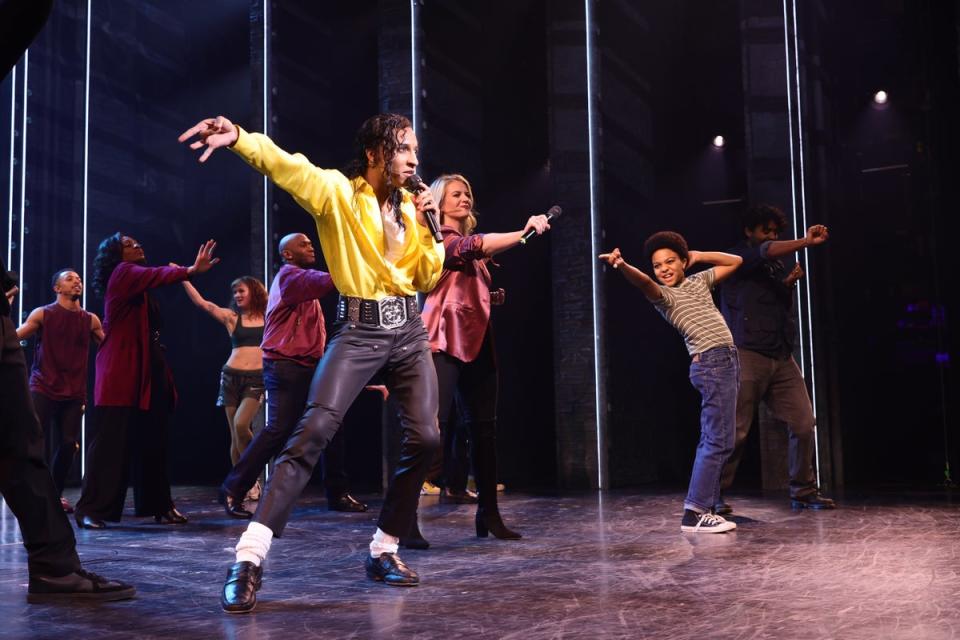

MJ the Musical is moonwalking into the West End – but how do you tell a story like Michael Jackson’s?

A Monument to Misconduct” splashed the Theatrely website. “Very Smooth, Somewhat Criminal” echoed the New York Stage Review. “No One’s Looking at the Man in the Mirror” attested The New York Times. When the notices for the Broadway opening of Christopher Wheeldon and Lynne Nottage’s Michael Jackson jukebox jamboree MJ the Musical landed in 2022, many gushed about the “megawatt” music and its eye-popping dance routines, but few could get around the curtained-off elephant in the auditorium.

With the Jackson estate involved in the production, MJ the Musical is told in flashback from an endpoint of 1992’s Dangerous tour, one year before the allegations of child abuse surfaced against pop’s biggest and most enigmatic superstar. This naturally made for a conflicted watch for many critics, particularly since two MTV journalists are cast as the villains of the piece for asking him intrusive questions about his monkey friends and plastic surgery, and a real-life Variety reporter was ejected from the premiere for asking the cast about the allegations.

Here was the rags-to-riches story of a tormented child star turned historic cultural phenomenon – one that was undeniably worthy of being told, remembered, and moonwalked poorly along to. But also one that cut off at a critical point, that sanitised and whitewashed a deeply stained legacy and reframed Jackson’s memory in a spotless – and ultimately more lucrative – light.

Audiences have flocked, more to jive than to judge. In two years, the musical has earned 10 Tony Award nominations, winning four, and has taken $170m (£135m) from 1.1 million tickets sold in New York. And next week, UK theatregoers will face the same discomfiting dilemma, as MJ the Musical opens at London’s Prince Edward Theatre. Meanwhile, another Jackson estate collaboration – Antoine Fuqua’s forthcoming Jacko biopic Michael – has come under fire from Dan Reed, director of the 2019 HBO documentary Leaving Neverland, which shed fresh light and attention on the stories of several of Jackson’s accusers.

“It seems that the press, his fans, and the vast older demographic who grew up loving Jackson are willing to set aside his unhealthy relationship with children and just go along with the music,” Reed wrote in The Guardian in February last year. Claiming to have since seen a draft of the movie’s script, he doubled down in a Sunday Times interview this month. “It’s an out-and-out attempt to completely rewrite the allegations and dismiss them out of hand, and contains complete lies,” he said. “You never even see him alone with any boys, when it is a matter of fact that he shared his bed with small children for many years.”

When your show is nothing without permission to use the music, but it seems the estate is hellbent on scrubbing clean their cash cow’s reputation, how do you tell a story like Jackson’s? His music and achievements are the stuff of pop history – the best-selling solo artist of all time, 15 Grammys, 400 million units shifted, and songs such as “Thriller”, “Billie Jean”, “Bad” and “Don’t Stop ’til You Get Enough” embedded into the core of popular culture, and that’s before you even touch on The Jackson 5. But no serious assessment of this deeply eccentric, charmed/cursed life can brush under the carpet the scandals that dogged his final decades.

To recap: in 1993 – amid much secretive, big-money deal brokering and story selling – Jackson was accused of molesting 13-year-old Jordan Chandler, one of numerous children the star was alleged to have spent nights in bed with at his Neverland ranch and elsewhere. With other children claiming not to have been abused by Jackson, and the singer denying all wrongdoing, that case was settled out of court for around $23m. Since Chandler subsequently refused to testify, no criminal charges were brought, through lack of evidence from an 18-month investigation that included 400 interviews.

A 1994 PBS Frontline documentary, Tabloid Truth: The Michael Jackson Story, set about exposing the profiteering that went on around the media’s frenzy for Jackson abuse stories, with his employees often taking their evidence to the press for payouts before telling the police. In 1997, Jackson won a $2.7m civil suit against Victor Gutierrez, the author of a book claiming to be based on Chandler’s diaries from the time, who had alleged that Jackson’s nephew, Jeremy, was a victim of Jackson’s abuse.

Jackson’s dependence on painkillers deepened, his health suffered to the point where he claimed he needed to be fed intravenously, and he lost several multimillion-pound contracts as a result of the scandal. With no conviction against him, it should have been possible to put the case behind him, particularly when the OJ Simpson trial arrived to overshadow it. But his 1995 album HIStory kept the story fresh in the public’s mind, awash as it was with Jackson’s reactions to what the track “Stranger in Moscow” called his “swift and sudden fall from grace”.

And in 2003, further accusations surfaced in the wake of Martin Bashir’s ITV documentary Living with Michael Jackson, in which the star defended his practice of sharing his bedroom with children (claiming he slept on the floor) and was filmed holding hands with 12-year-old former cancer patient Gavin Arviso.

Amid calls for Jackson to lose custody of his children, his team released a two-hour rebuttal documentary The Michael Jackson Interview: The Footage You Were Never Meant to See. Nonetheless, criminal charges were brought after Arviso told police that Jackson had abused him several times when he was 13, having shown him pornography and given him wine in soda cans, which Arviso said he called “Jesus juice”.

During the trial, Jason Francia, the son of one of Jackson’s housemaids, also claimed he had been abused at Neverland between the ages of seven and 10, contradicting his 1993 statement to police, and several witnesses attested to seeing Jackson molest child actor Macaulay Culkin. Appearing for the defence, however, Culkin denied Jackson had assaulted him. Jackson was ultimately acquitted of all charges.

Despite the verdict, and even before so-called “cancel culture” had the online infrastructure to wield major cultural influence, the impact on Jackson’s life and career was devastating. He struggled to find sponsors and merchandise partners for his sell-out tours, and in 2021, a judge observed that the biggest pop star in the world had “earned not a penny from his image and likeness in 2006, 2007, or 2008, [showing] the effect those allegations had, and continued to have, until his death”. Almost 20 years later, his acquittal also poses a dilemma to a new generation of music and arts consumers raised on condemnation: the evidence seems substantial, but the legal conclusion was decisive.

With no further charges possible following Jackson’s death in 2009, we’ve now entered the era of trial by posthumous media. In 2013, Australian choreographer Wade Robson reversed the testimony he had given at the 2005 trial, to claim that Jackson had abused him over seven years as a child. The following year, another former underage Neverland houseguest James Safechuck also refuted his own testimony from 1993 to make similar claims. Lawsuits from both against the Jackson estate and his corporations were dismissed, but Reed’s Leaving Neverland doc, focusing on their stories, revived questions around Jackson’s conduct.

Again, the Jackson team produced a rebuttal film, 2019’s Michael Jackson: Chase the Truth, which struggled to convince viewers that the shocking and moving testimonies from Wade and Safechuck in Reed’s film were inaccurate and financially motivated.

That strand of the story is about to be rebooted. The dismissal of the suits brought by Wade and Safechuck was overturned by a Californian appeals court, which decided that Jackson’s corporations could be held responsible for his actions. Their cases will finally come to court shortly, with the accusers pushing for a trial date before the Michael biopic’s April 2025 debut in an effort to hinder the estate “rewriting the history”.

In the meantime, MJ the Musical arrives into a confused sense of moral malaise. With so many heritage acts having their interviews, X/Twitter feeds, and out-of-print autobiographies scoured for potentially career-ending moral or criminal transgressions, fans are being forced to numb themselves against the potential crimes, bigotries and wrongthink of their musical heroes, or else cast away huge swathes of the music they love. It’s why Jacko superfans have filled the aisles of MJ nightly, arguing both publicly and internally that a lack of legal conviction justifies their every sparkle-gloved crotch-grab. The dazzle in the songs, for many, obliterates the shadows around the man.

Alongside the high-functioning evolution of our communal radar for offence, however, we’ve also honed a keen scent for cynicism. Whenever an artist’s estate is involved in a biographical production, almost always downplaying or brushing over the less savoury and unfavourable aspects of the star’s life, it becomes a dissatisfying, discomfiting experience that the discerning viewer is reluctant to condone. It treats us all like useful ticket-snaffling idiots, pawns in a multibillion-dollar PR game.

It was there in the glossing over of James Brown’s domestic abuse in 2014 biopic Get on Up, in the tongue-in-cheek pantomime booing of the Ike Turner actor at the end of jukebox musical Tina, and it reaches its apex with MJ the Musical. It’s a fun night out, we get it. But unless such stories are delivered with honesty, transparency, and occasionally some very dark home truths laid bare, theirs is a guilt-tainted boogie.