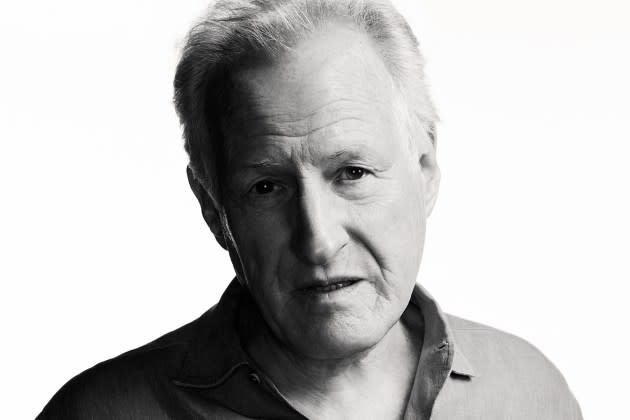

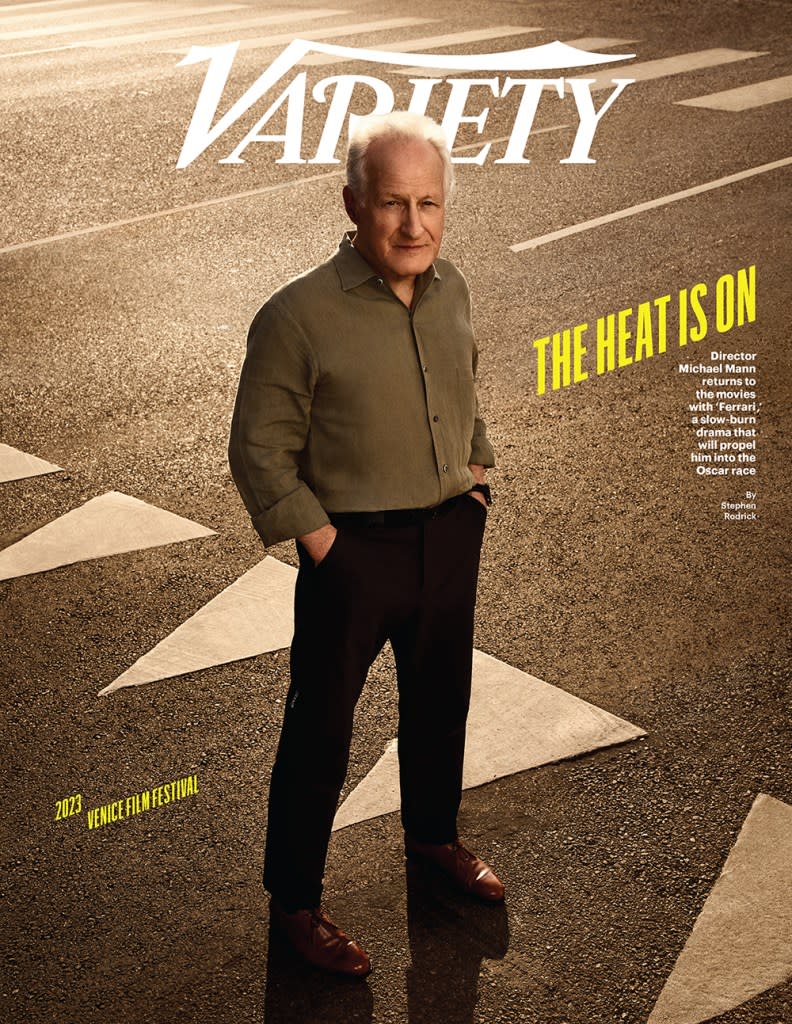

Michael Mann Fulfills a 30-Year Journey Directing the Operatic, Thrilling ‘Ferrari’ — And Teases ‘Heat 2’: ‘I Don’t Think About Mortality. I’m Busy’

Michael Mann is running out of time.

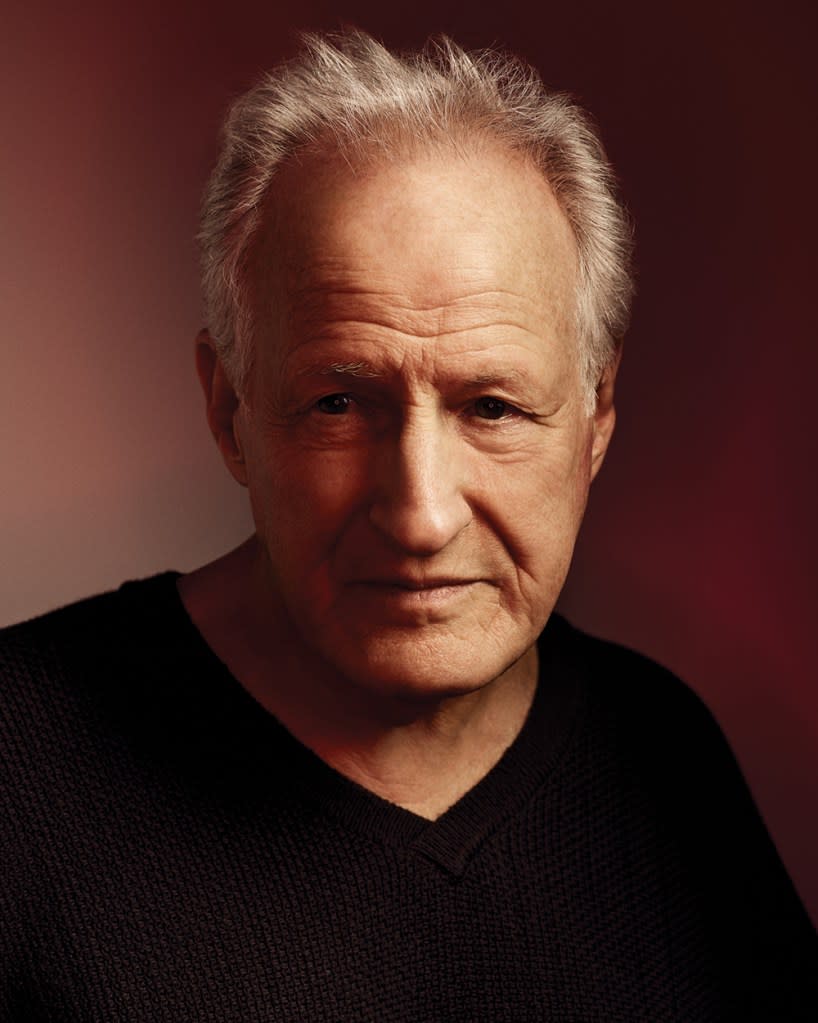

I am in the 80-year-old director’s West Los Angeles office, talking to him about his new film, “Ferrari,” and he asks me to move closer and speak up. He then fills the room with beeps and boops as he takes a minute to start his own tape recorder — I already have two running. I was told, a few days ago, that Mann, a known control freak, prefers to have, if not the questions, then the areas of interest of his inquisitor in advance. I thought this was rude and decided to comply by overwhelming him with convoluted queries like a white-shoe law firm doing a document dump on an underfunded plaintiff.

More from Variety

Michael Mann's 'Ferrari,' Starring Adam Driver, to Close New York Film Festival

Neon Buys Michael Mann's 'Ferrari,' Racing Drama With Adam Driver Will Open in 2023

Mann is unfazed. He glances at my multi-page memo before sorting through preproduction photos and notes for “Ferrari” that he wants to show me. (These should not be mistaken for the pre-production “Ferrari” files that fill half a room in another office.) His film examines three pivotal months in the life of Enzo Ferrari (Adam Driver), the company’s namesake and founder. In 1957, Ferrari is going broke, he’s just lost a son, his drivers are dying and he is fighting with his wife, Laura (Penélope Cruz), who doubles as his chief financial officer. Laura doesn’t know that Ferrari has a son with Lina (Shailene Woodley), his true love and mistress, who lives in a country house outside town. The only way Ferrari can keep his company and his life together is if his racing team does well in the upcoming Mille Miglia, a fatality-ridden 1,000-mile race across Italy.

“Ferrari” is largely set in Modena, an insular town an hour outside Bologna where Ferrari lived and built his cars. Mann slides a homemade booklet from his first visit to Modena across the desk. It is filled with his photos of Ferrari’s barbershop, the exterior of Ferrari’s home and the Cimitero di San Cataldo, where Ferrari’s only son with Laura, Dino, was interred after dying of muscular dystrophy at the age of 24 in 1956, a year before the film is set. All the locations eventually made it into the film.

Many of Mann’s photos feature a distinctly Italian light that appears repeatedly in the film and that cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt attributes to Mann’s love of the light in the paintings of Caravaggio and other 16th-century Italian Renaissance painters. After seeing a few more, I ask Mann to flip back to the photos he took of the Cimitero di San Cataldo. The Ferraris’ crypt plays a pivotal role in the film. In real life, it’s where Ferrari was interred, so his gravestone had to be covered up during shooting.

Then I notice a familiar-looking man with black hair standing among the graves in one of the photos. I point him out, and Mann breaks into his first smile. “That’s me in 1993.”

It takes me a moment to comprehend what Mann is telling me: He has been in preproduction on “Ferrari” for three decades. (His original producing partner was the late director Sydney Pollack.) In the interim, Mann made seven other films, including “Collateral,” “The Insider” and “Heat.” He raised four daughters, dabbled in prestige television and wrote a bestselling novel, expanding the “Heat” universe.

Actually, 1993 wasn’t even the true start day. Back in 1967, Mann was a film student in London learning his craft, dodging the Vietnam draft and living on 5 pounds a week. One day he trudged out of the London Underground and was met with a vision. “Something rolls by,” Mann tells me, his hazel eyes full of light. “It was a Ferrari 275 GTB four-cam. It was just such a gorgeous, sensual sculpture that’s moving.” He describes it in the way that other men remember the first time they laid their eyes on their wife. “It was just this integration of performance speed and sheer beauty.”

Mann was 24 at the time and tells me that he wondered, back then, what led to the building of such an extraordinary vehicle. Now it’s half a century later, and “Ferrari” is finally done. Later, after the three recorders have been turned off, the tension drains from Mann’s face and he grins. “It happened when it happened.”

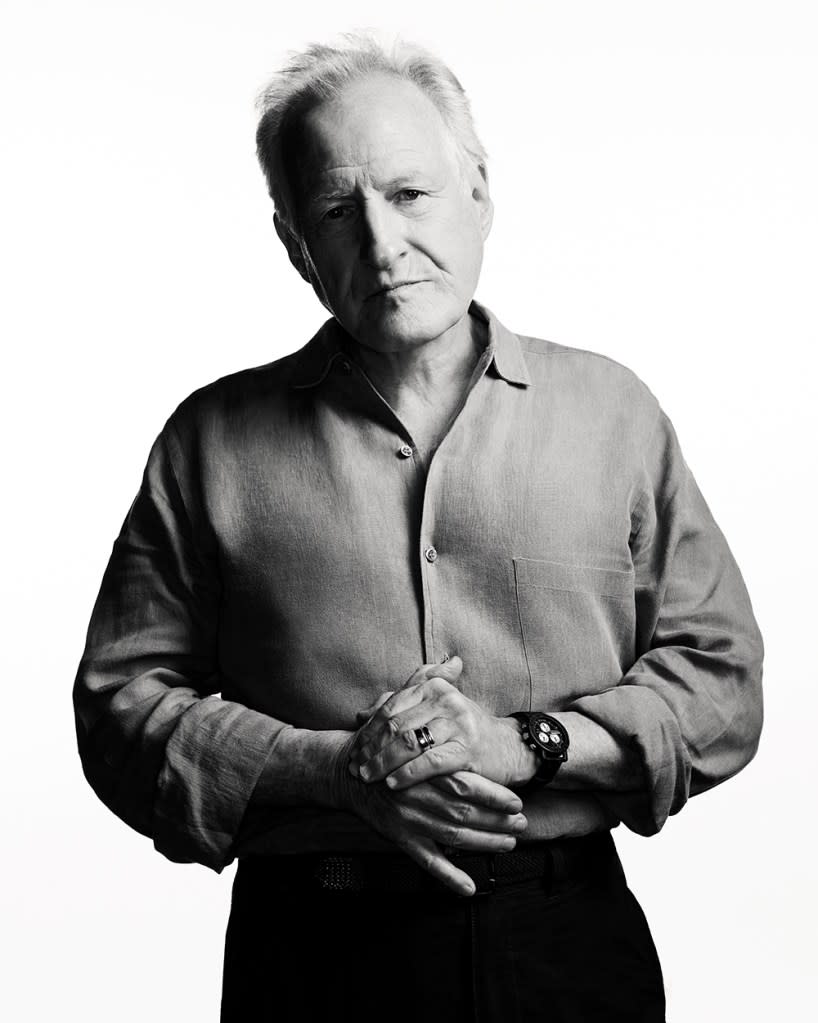

Mann is on Italian time, so he’s been working for many hours when he pulls into the parking garage of his office building for our talk. He parks his Porsche not far from another of his sports cars — a Ferrari shrouded in a tarp featuring an etching of a prancing horse, the car company’s iconic symbol. He makes his way to his third-floor office, his white hair askew.

He is a slight man who moves stealthily, a waif sliding into an elevator just ahead of the closing doors. He asks for my indulgence while he makes a cup of coffee. Unfortunately, the machine is on strike. Mann turns it on and off. He checks the plugs. He pulls out the filter. Nothing. Mann’s films are intricately plotted out in advance — they feel invented rather than written — but a lifetime of research and problem-solving can’t help him now. He throws up his hands in mild frustration and turns to an assistant. “I don’t know. Read the instructions or call the manufacturer. I can’t figure it out.”

His accent still echoes his native Chicago, specifically Humboldt Park. It hasn’t changed much since his teenage days at Amundsen High School, when he and his brother tried to burn down a chain grocery store that was crushing his father’s small shop. (They did not come close to succeeding.)

Mann is dressed in beige and off-white, a nondescript color palette that would have led him to being booted off the set of “Miami Vice.” He examines two small expanding blue circles on his white pants. “I guess this is what happens when you carry pens around in your pockets,” he says.

I tell him I have dozens of shirts redesigned by my Pilot pens. He nods grimly. “We share a common affliction,” he says.

Mann can come off as cranky and impatient. You can hear this when he brusquely swats away premises and theories from podcasters who only wish to praise him. He can also be engaging and endearing if he feels like you know your stuff. Fortunately, I had eight days and my family was out of town.

His stress level is understandable. It’s entirely possible that Mann’s ability to film “Heat 2,” a longtime dream, will be contingent on how well the $95 million-budgeted “Ferrari” does. His last film, 2015’s “Blackhat,” was both a commercial and a critical disappointment. The film starred Chris Hemsworth as a paroled cybercriminal pursuing a hacker stealing data with horrific consequences and has many of the usual Mann flourishes — a shootout in a tunnel, dark romance and Mann attempting to show megabytes coursing like blood through veins as they move across the world in real time. (Some loved the data scenes; some became nauseous.) The film never quite gelled, earning $19.6 million worldwide against a budget of $70 million.

“It’s my responsibility. The script was not ready to shoot,” says Mann. “The subject may have been ahead of the curve, because there were a number of people who thought this was all fantasy. Wrong. Everything is stone-cold accurate.” Mann says there are films he has made where he wouldn’t change a frame — “Heat,” “Collateral” and “The Insider” — but “Blackhat” isn’t one of them. In 2016, he reordered the cyberattacks in the film for a Brooklyn Academy of Music retrospective and liked the results. “I’ve revised ‘Last of the Mohicans’ three times, and now it’s shorter than the original,” he says with a laugh.

Maybe with the revisions, New Yorker critic Richard Brody would not have proclaimed, “‘Blackhat’ is proof of why, by and large, good riddance to the ‘midrange drama.’” It’s a good line, but not quite fair. Mann’s entire career is made up of midrange dramas, and many of them are among my favorite films. I can remember every theater where I have seen one of his creations, the seats, the architecture. The theaters become a portal into his perfectly curated Man vs. the Monolith world, whether it is Daniel Day-Lewis’ Hawkeye against the British Empire in “The Last of the Mohicans,” Russell Crowe’s Jeffrey Wigand taking on the tobacco industry in “The Insider” or Will Smith’s Muhammad Ali battling the white power structure of 1960s America in “Ali.”

Mann’s ethos was already present in 1980’s “Thief,” his first feature, in which James Caan plays a Chicago safecracker taking on the mob. For that film, Mann had a criminal teach Caan the tools of the trade. On-screen, you are actually seeing Caan drill into a seemingly impenetrable safe.

Recreating reality is a trademark of Mann’s movies. When he made “The Insider,” the 1999 film about “60 Minutes” buckling under to the tobacco industry, Mann found a janitor to photograph the “60 Minutes” office. “The set we built was an exact duplicate,” he says.

Mann is always on a quest for the meticulously authentic experience. He describes how he asks himself some basic questions when he is building a movie universe. “What is this world?” he wonders. “What does it feel like? And what do I have to do to bring an audience to dream it?” He adds, “I know what I want when I go to a movie: I want to be there. I want to be in a wide-awake dream for a couple of hours.”

To create that kind of transported reality requires an extraordinary level of buy-in from his actors. Mann had Day-Lewis hunt and forage for his own food in the months leading up to the shooting of “The Last of the Mohicans” and pushed Tom Sizemore and Val Kilmer to case a bank before filming the final bank robbery scene in “Heat.”

This all has made Mann legendary and slightly infamous. I talked with creative types who have worked with Mann through the years. None of them felt comfortable going on the record because of the actor and writer strikes but also because they all hold true admiration for Mann’s work and didn’t want to be on record saying he could be a jerk. Their general consensus could be summarized as “Michael Mann is a lot.”

“In many cases, you are kind of making the movie with the filmmaker,” says Messerschmidt, who has also worked with Ridley Scott and David Fincher. “It’s not at all a criticism of Michael — it’s actually a compliment — but Michael made this movie. Everyone around him is just trying to help.”

“Ferrari” is best understood as an old-school melodrama, a description that Mann happily embraces. The film takes place over the summer of 1957 as Enzo’s beloved Ferrari and his personal life hang in the balance. “Everything he’s been collides with what he might become, and the company has gone bust,” says Mann with some glee. “His wife finds out about the other woman. It’s a spectacularly operatic melodrama in real life.”

Mann is not exaggerating. There are actually scenes set at the opera. Driver’s performance as Ferrari sees the auto icon maneuvering through his life with the help of droll one-liners that provide more laughs than the combined works of Mann’s previous half-century. Ferrari has a tiny wisecracking mother named Adalgisa delightfully played by Daniela Piperno. You will love her and also contemplate writing a letter of protest to the Italian Anti-Defamation League. She dresses all in black and has a bag packed for when the Italian people turn on Ferrari and they must flee the country.

Laughs aside, Mann gives a Cassavetes-level portrait of Ferrari and Laura’s marriage falling apart. It is just a year after their son has died, and their union founders on grief, infidelity and Ferrari’s impending insolvency. At the root of the problem is a mother’s fury that her husband promised to save her boy and failed while his cars thrived and grew faster. Eventually, Laura confronts Ferrari and he is so grief-stricken he can only speak of himself in the third person:

“The father, he deluded himself: ‘The great engineer. I will restore my son to health.’ Swiss doctors, Italian doctors. Bullshit. I could not. I did not.”

There is a memorable scene where Ferrari and Laura visit Dino’s grave on the same morning, but separately. The usually emotionally shut-down Ferrari breaks as he has a conversation with his dead boy. Laura then arrives. She has a silent conversation with her son, her face full of joy, and then it crumples as she knows he cannot answer back.

“Penélope connected with Laura on almost a primordial level from the first day,” says Mann. The director and actress were completely in sync. He says, “We would have the same thoughts about Laura on the same night.”

One night, they both wrestled with how to give Laura a hint of her burden through a physical trait. “We both came in the next morning saying Laura should wear orthopedic shoes to give her a waddle,” recalls Mann.

All of Mann’s achievements didn’t make raising the money for an undertaking like “Ferrari” any easier. In the early 1990s, he first read the late Troy Kennedy Martin’s script that was based on Brock Yates’ 1991 “Enzo Ferrari: The Man and the Machine,” a book Mann loved. It wouldn’t be a cheap film to make, and for years it was thought that a movie about Ferrari was too exotic an idea for an American audience raised on NASCAR and “Days of Thunder.” Then, Formula One grew in popularity in the United States, and the idea bubbled up again about a decade ago.

In late 2015, the film was on the precipice of production with Christian Bale as Ferrari, but then Bale dropped out, with the trades reporting he didn’t feel he had the time to put on the weight needed to portray the hefty Ferrari. Ironically, Mann got an executive producer credit for consulting on 2019’s “Ford v Ferrari,” with Bale starring as British race-car driver Ken Miles. It wasn’t until 2021 that the money emerged to start shooting in the summer of 2022.

“We had very successful foreign presales, and that enabled us to put it together along with the Italian tax credits,” Mann tells me. “That enabled us to make the picture because it’s not an inexpensive film.”

As the SAG-AFTRA and WGA strikes rage on, Mann is proud that his film has no ties to the major studios. “The origins of the movie and the content of the screenplay and the movie that you saw do not fit into the kind of film that would be embraced by the conventional studio system,” he says. “It’s truly appropriate that it is an independent film being distributed by Neon, a very independent distributor.”

Mann is old enough to have endured the 1988 work stoppage, where the consensus was creatives gave away then-lucrative home video revenue, and he supports SAG-AFTRA and the WGA’s efforts not to give away the store on streaming in 2023. “I think that the struggle is kind of late-stage capitalism,” he says. “Writers are massively underpaid — even top feature-film writers. They all start with this.” He holds up a blank piece of paper. “We begin with nothing, absolutely nothing.”

He offers “Ferrari” as an example. “Troy and the screenplay, I changed it around quite a bit. But the absolute foundation and the beating heart of this movie is what Troy did.”

When “Ferrari” debuts in Venice, there will be much talk of the 3D imaging that allowed Mann to construct perfect facsimiles of Ferraris from the mid-1950s. And techies will marvel at the filtered sound he used to re-create the precise noise made by these metal beasts. But these things will only underscore that 1950s auto racing was a brutal killing field. The 1957 Mille Miglia was marred by a horrific crash outside the village of Guidizzolo that killed Ferrari driver Alfonso de Portago and 10 spectators, including five children. (The race was never again run in its original format.)

Before filming, Mann had Messerschmidt and his camera crew study the footage of a 1955 crash at Le Mans that killed more than 80 spectators when Pierre Levegh’s Mercedes-Benz exploded and the remnant fireball of his car buzz-sawed through the crowd. Mann then made a trip to Guidizzolo before shooting began. There was a farmhouse set not far from the road. He walked around and talked to residents through translators. Eventually, a man in his 70s approached him. “I was there,” the old man told him. He pointed at the farmhouse nearest the road. “That is where I grew up with my brother.”

Mann says, “He told me he and his brother heard the engines and ran toward the road. His brother was older and faster, so he was closer when the crash happened. He died, but his brother survived because he was slower.”

Mann reimagined the event, incorporating the point of view of the boy’s family. The resulting scene is one of the most violent and emotionally crushing I’ve ever seen. Mann is unsparing — there are severed body parts and decapitated torsos. I tell Mann that my father had been a Navy pilot who was killed in a crash off the USS Kitty Hawk. I’d written a book about it, but it wasn’t until I saw the chaos and destruction of the Guidizzolo scene that I had a visceral understanding of what happens to body and metal when a machine destroys itself at high speed.

Mann nods sympathetically. He says, “All I can say is that is exactly how it happened.”

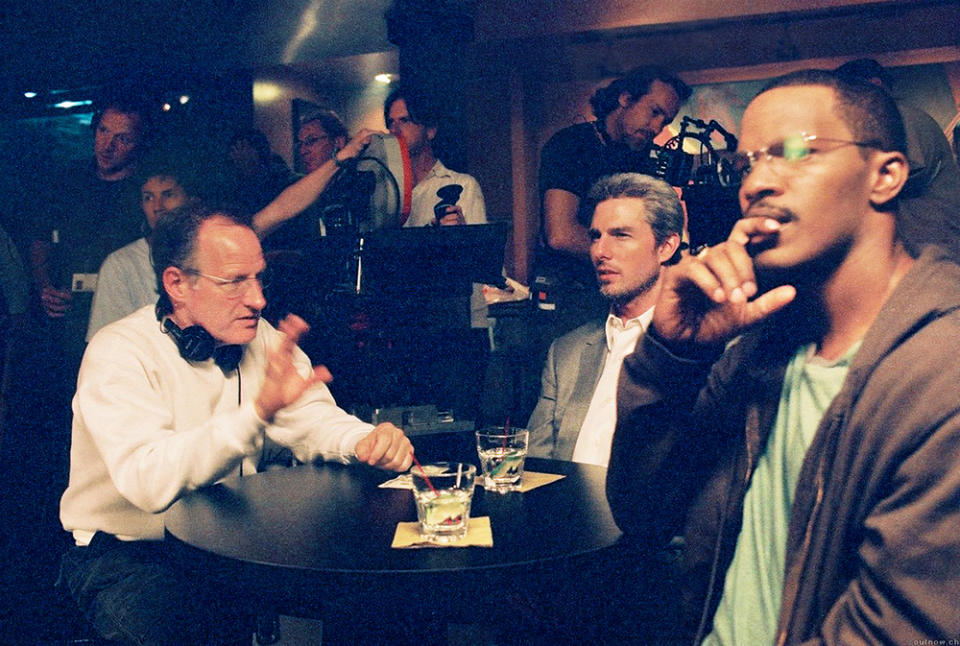

Mann has assembled a remarkable body of work, but his calling card will always be 1995’s “Heat,” his crime epic starring Robert De Niro and Al Pacino. This doesn’t bother him. In fact, he delights in sharing with me the genesis of Pacino’s L.A. detective Vincent Hanna shouting, “She’s got a great ass, and you’ve got your head all the way up it,” at an unsuspecting Hank Azaria, whose character is having an affair with the Ashley Judd character. Mann laughs at the memory. “Al’s best takes are always five, six or seven,” he says. “It’s never the first two. He’s experimenting around, and then after five, six or seven, maybe it’s a small change. After that, he would deliver a take that was fantastic.”

But Pacino wasn’t done. Once they had a good take in the can, he’d ask Mann if he could do “a wild one.” Mann always said yes. Sometimes it was brilliant, sometimes it was terrible. Often it was hilarious. Alas, this was Azaria’s first day on set.

“I neglected to tell him that we had a habit of doing this,” says Mann. “Al just flipped this guy up and down and cut loose, and that look of shock and amazement on Azaria’s face is because we’re going completely off the script into something totally wild.”

It was rumored Pacino’s character was a cokehead, something Pacino and Mann have copped to in recent years. But Mann gives me one more detail. He tells me he shot a scene of Pacino snorting coke off a dagger he carried in the small of his back. Mann says he cut it, telling me it was “too strong a message.”

All of the “Heat” talk is not merely an artist playing his greatest hits for an adoring crowd. Last year, Mann published a well-received 500-page doorstop of a novel called “Heat 2,” co-authored with thriller writer Meg Gardiner. Mann’s passion is creating deep storylines for his characters, and many of their experiences never appear on-screen but inform their actions. The book allowed Mann to bring some of those stories to the surface. The tale of Neil McCauley, the crew leader played by De Niro in the film, and Pacino’s Hanna is told as both a prequel and a sequel to the “Heat” timeline.

“In the prequel, I don’t want them to be the same people that they are in the movie,” Mann says. “I want them to be very different. It’s what befalls them — the conflicts, the tragedies that happen to them — that made them into the people they are.”

In the book, the reader sees how McCauley’s backstory of foster homes and a loved one bleeding to death in his arms is what leads him to a life of emotional detachment. “For Neil, it’s the events of the prequel that give him the gospel ‘Don’t have anything in life you can’t walk away from in 30 seconds,’” says Mann.

A recurring theme in Mann’s work is time — specifically not having enough of it, whether it is De Niro getting out of a bank before the heat arrives or Tom Cruise completing his kill list before daybreak in “Collateral.” “Ferrari” is no different: It includes a scene where a dozen men pull out stopwatches during Mass to time a rival’s car circling at a nearby track. I indelicately ask Mann if he fears that he is running out of time to get “Heat 2” made.

As an answer, he launches into a convoluted metaphor about a friend of his who is an architect in his late 80s who has multiple projects in the works and a desire to die on one of his construction sites.

The next afternoon, though, when we meet again in a high-rise above the 405 as L.A. approaches magic hour, Mann asks for another take. “You asked me about mortality, but I didn’t really answer,” he says. He takes a sip of coffee. “The thing is, I don’t think about mortality. I’m busy. What good would it do me? If I absolutely had to make ‘Heat 2,’ I wouldn’t have got lost in this beautiful story of Ferrari. And I took two years to write a novel.” He offers a mischievous smile and adds, “Fortunately, it became a New York Times No. 1 bestseller.” Then he says, “The things I’m into are things that fascinate me and keep me moving forward.”

I’m not sure I believe him. Mann has just spent two years writing “Heat 2,” vastly expanding the world of characters he has lived with for more than 30 years — the same amount of time “Ferrari” was in preproduction. He is a filmmaker; this is what he does. It’s hard to see him not being anxious to play the hand if someone gives him the chips.

Maybe Mann senses my skepticism, but he has to go. The light is starting to fade. He’s got things to do. He offers a parting thought. “Don’t misunderstand,” he says. “I want to make it. But if I don’t, I won’t be incomplete.”

Then he slips into a waiting elevator and is gone.

Best of Variety

'House of the Dragon': Every Character and What You Need to Know About the 'Game of Thrones' Prequel

25 Groundbreaking Female Directors: From Alice Guy to Chloé Zhao

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.