From menace to miracle: How ‘padi angin’ may solve future rice scarcity in Malaysia

KUALA LUMPUR, May 31 — Agricultural weeds have long been formidable adversaries in paddy fields worldwide, competing with crops for resources and significantly reducing agricultural yields.

One such weed, weedy rice — called “padi angin” in Malay — has garnered attention due to its persistence and impact on rice cultivation. However, recent research suggests that weedy rice may hold untapped potential that could benefit agriculture.

Speaking to Malay Mail, academic Song Beng Kah from the School of Science at Monash University Malaysia explained that the story of weedy rice starts with the domestication of its wild ancestor, Oryza rufipogon, more than 10 years ago.

The associate professor said early farmers selectively bred rice plants to have traits that made harvesting easier.

“For example, they chose plants that were less likely to scatter their seeds, making it easier to control the cultivation.

“This domesticated rice, known as Oryza sativa, kept some genetic traits from its wild relatives but was better suited for farming because it did not easily drop its seeds,” he told Malay Mail in an interview.

He then went on to say that the weedy rice, which emerged three decades ago in Peninsular Malaysia originates from two primary processes, which are hybridisation — involving the interbreeding of cultivated rice with wild rice and inheriting traits like easy seed shattering — and a reversal of domestication due to genetic mutations, leading to the reacquisition of wild-like features, such as seed shattering, rendering it challenging to control in cultivated areas.

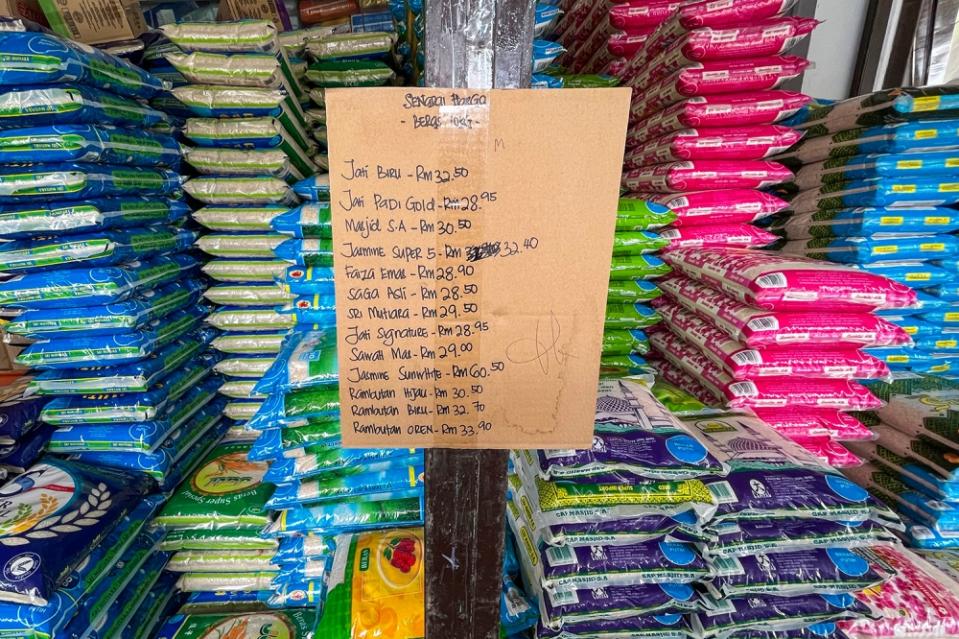

Packs of rice on sale at a grocery shop in Shah Alam, August 23, 2023. — Picture by Miera Zulyana

Challenges posed by weedy rice

Song said weedy rice presents numerous challenges to farmers as it tends to compete with cultivated rice for vital resources, such as nutrients, water, and sunlight, which can lead to significant reductions in crop yields, causing economic losses.

Moreover, he said the physical similarity between weedy rice and cultivated rice makes it challenging to differentiate and remove weedy rice during the early stages of growth.

“As weedy rice grows, it competes with regular rice for nutrients and fertilisers, leading farmers to expend time and resources in their care due to the difficulty in distinguishing between them, particularly in their early stages.

“Consequently, farmers incur losses, impacting rice companies involved in processing the rice consumed,” he said.

He said due to this, the decline in rice supply affects not only export markets, such as India and Thailand, but also domestic production.

In 2010, the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (Mardi) collaborated with BASF to develop Clearfield technology using Clearfield rice seeds and herbicide named OnDuty, to control the weed for several years in peninsular Malaysia.

However, the issue resurfaced when new generations of herbicide-resistant weedy rice emerged, stemming from local farmers using unregistered herbicides and not following the Clearfield rice planting guidelines.

“It’s a complex issue because initially, we believed Clearfield technology could resolve it for at least a decade. However, with the emergence of super weed rice, we find ourselves back at square one, confronting an even more severe situation than before.

“This challenge is not confined to Malaysia alone. It’s a global concern. Countries such as China, Thailand, Myanmar, Taiwan, the United States, and even Italy, are wrestling with it. The distinction lies in that some countries, like the US, lack wild rice; thus, their predicament arises from DNA mutation mechanism,” he added.

Song explained that this pertains to weedy rice problems in general, rather than the “super weedy rice” resulting from the misuse of Clearfield rice planting practices.

He further said that relatively few countries have adopted Clearfield technology to address the weedy rice issue — only the US, some South American countries, Italy, and Malaysia have invested in this technology.

Once invaded by weedy rice, fields suffer significant losses, mainly attributable to the weed’s tendency to shatter seeds, its unpalatable taste, and the difficulty in harvesting its grains.

Academic Song Beng Kah from the School of Science at Monash University Malaysia speaks to Malay Mail during an interview at his office in Bandar Sunway, May 14, 2024. — Picture by Yusof Mat Isa

Harnessing the potential of weedy rice

According to Song, despite its challenges, weedy rice holds potential as a genetic resource for future rice breeding efforts as its genetic diversity, referred to as germplasm, offers a wide range of traits that can be beneficial for developing new rice varieties.

He explained that researchers can utilise these genetic resources to breed rice with desirable traits such as disease resistance, heat tolerance, and salt tolerance.

“Wild rice is crucial because it comes in various types, all belonging to the same species but with different traits like heat resistance, salt tolerance, and high pH tolerance. This is an example of how scientists use germplasm, including wild rice, to develop new rice varieties.

“They also have many antioxidants because of their colours. This contributes to addressing the rice shortage issue,” Song added.

He said germplasm refers to genetic materials, acting as a reservoir of genetic resources for future breeding endeavours.

For instance, Song added when aiming to cultivate a novel variety of regular rice, various combinations are tested using genetic markers for cross-breeding to determine their effectiveness.

“Germplasm serves as a crucial genetic resource for future rice breeding endeavours. To develop new rice varieties, access to germplasm is essential. Cross-breeding requires the involvement of diverse types of rice,” he said.

Song then went on to say the primary challenge in the rice industry stems from the difficulty in distinguishing between weedy rice and regular rice, as they appear remarkably similar, making it hard to detect contamination until the weedy rice begins to flower.

Green paddy slowly turns yellow, an indication that it’s ready to be harvested. — Picture by Sayuti Zainudin

As part of the efforts, Song said Monash University Malaysia is undertaking a project aimed at developing a biomarker to differentiate between the two.

“In terms of funding, Monash University is spearheading this project with support from the government and overseas collaborators. If successful, Malaysia could lead the way in solving this issue,” he added.

A “biomarker” — short for biological marker — is an objective indicator that reflects the status of a cell or organism at a specific time, which can function as an early indicator of health conditions.

In a letter sent to Malay Mail entitled “A padi angin genetic journey to solve local white rice shortages”, Song had previously said factors like climate, rice varieties, fertiliser quality, and pests impacting global rice harvests, a persistent challenge in the rice production chain has been the infestation of weedy rice in the fields.

This, he said, has caused the Malaysian rice industry to incur losses exceeding RM90 million per season over the last 30 years.

Citing the statistics from the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations, he said the price of indica rice (Indian rice), which is popular in South-east Asia and known for its long, slender grains, has been on the rise since 2022.

As of March, the average price index was 154.0 points, marking a 22.9 per cent increase compared to the same period last year.

“In this wave of rice supply crisis, Malaysia which is highly dependent on India and Thailand for these two types of rice, have felt the pain of soaring rice prices,” he said in the article.