What Meets the Eye: Giacometti's artistic genius showcased at major exhibition in Denmark

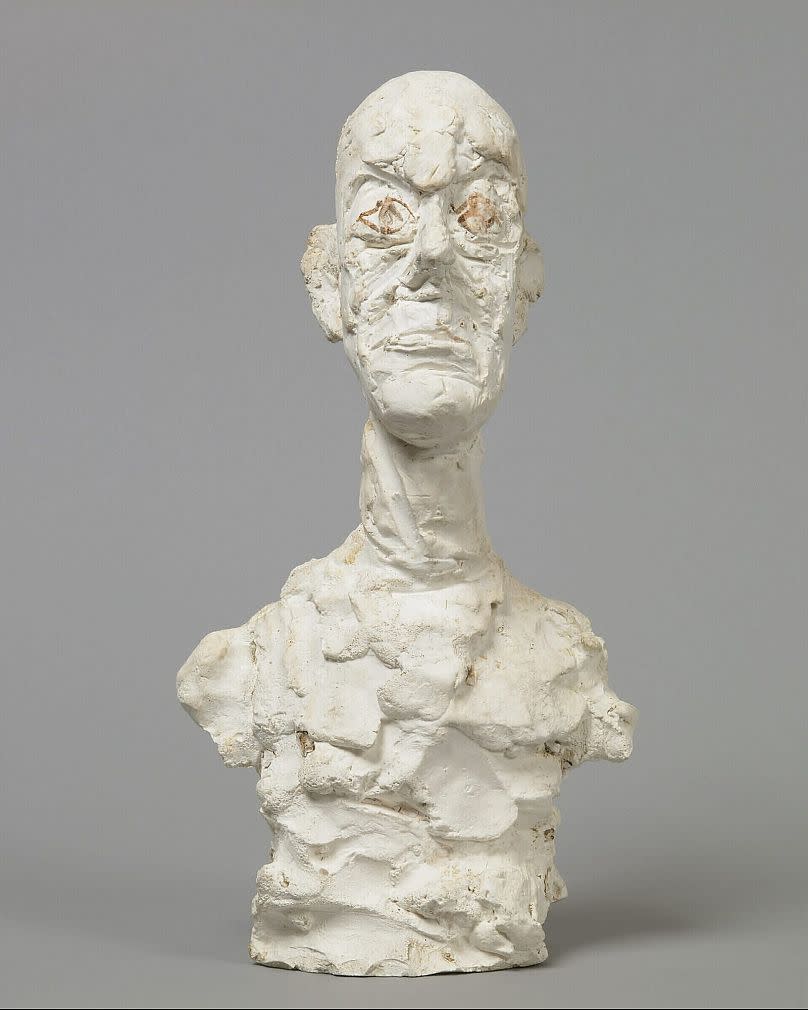

Alberto Giacometti’s fame rests on his sculptures.

He’s considered one of the 20th century’s most important artists and is renowned for creating the most expensive sculpture ever auctioned - “Pointing Man” that fetched over $141 million (€131,000) in 2015.

But the scope of Giacometti’s art goes far wider than that.

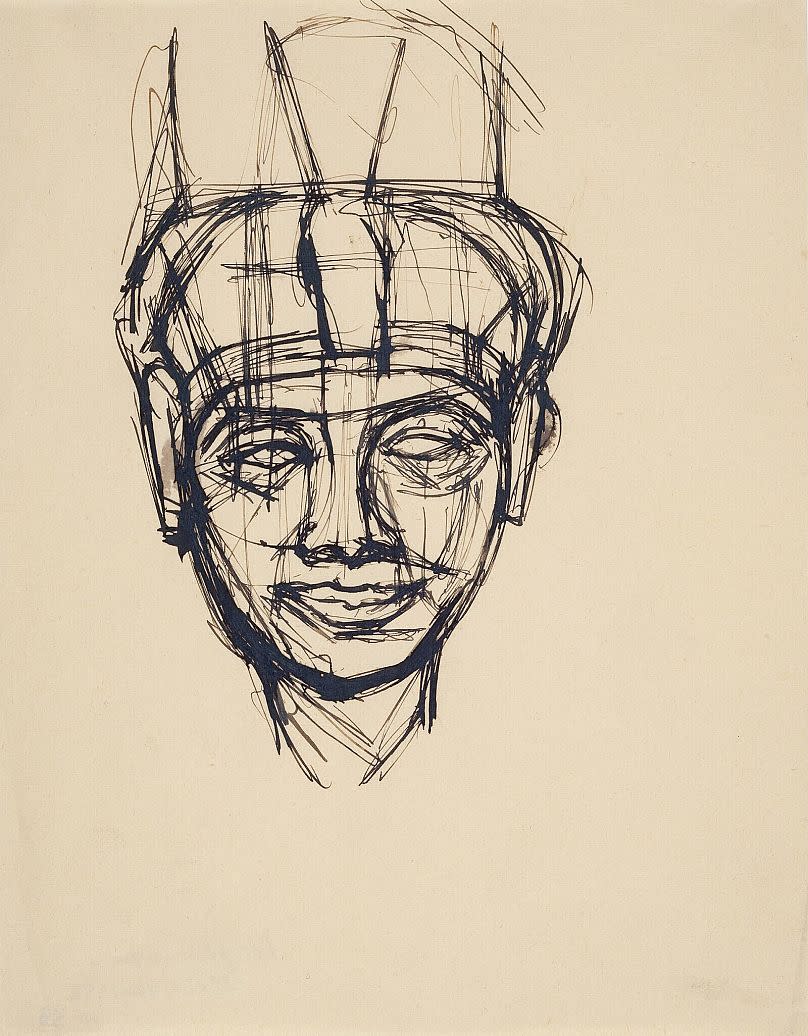

"He was a sculptor foremost, but he did paint, and he did draw a lot also,” says chief curator Thomas Lederballe Pedersen. “Most of us come to experience him as a sculptor, but still, as you can see here, there were paintings, and also drawings in his work at that time."

Created in collaboration with the Fondation Giacometti in Paris, a new exhibition, “What Meets the Eye” at SMK, Denmark’s National Gallery, contains around 90 of his works.

Visitors can experience some of Giacometti’s most popular masterpieces, including “The Nose” (1947), “The Cage” (1950-51) and “Walking Man” (1960). There’s also a number of lesser-known works rarely seen on public display.

Together they provide a unique insight into how Giacometti, who died in 1966 at the age of 64, shaped his approach.

Meet Philip Colbert: The British pop artist who became a lobster

Picasso sculptures take centre stage in must-see exhibition at Bilbao's Guggenheim

Giacometti's artistic evolution: From surrealism to physical reality

"André Breton (French writer and poet) is quoted for saying; 'But everyone knows what a head looks like.' And actually, that's the big conundrum for Giacometti from that time and onwards. He doesn't know what a head looks like,” says the exhibition's chief curator, Lederballe Pedersen.

“He doesn't know what a figure looks like, and he tries to get to an essence of what you see when you see something. What constitutes a figure visually when you see it. How do you recognise a figure as a figure, a human being as a human being?"

The exhibition takes its starting point in the 1920s and 30s, a period that left a decisive mark on Giacometti’s art. In 1934, he turned away from the Surrealist fascination with humanity’s inner life and instead began to take an interest in the physical reality.

"The middle of the (19)30s, he decided to go to human figure,” explains Emilie Bouvard, the director of collections and scientific programmes from the Fondation Giacometti in Paris.

“We don't really know why. I must say, if I go on a psychological level, his father just died, and his father was a post-impressionist painter interested in representation of the world. So, maybe that's why that was a psychological aspect."

World War II and its impact

During the Second World War, Giacometti took refuge in Switzerland, unable to return to his studio in occupied Paris. "He lived in occupied Paris during about one year, and then he wanted to see his mother because he had very strong link with his mother,” explains Bouvard.

“So, he went to Switzerland and then he couldn't come back. So, his studio, all his artworks. I mean, the whole he has done for 20 years, it was in Paris, and he couldn't come back."

From 1941, Giacometti came into contact with thinkers, including French philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. Philosophical questions about the human condition began to play a central role in his art.

After the Second World War, he entered a period of intense productivity, creating some of his most famous sculptures. “He's trying to get to an essence,” explains Pedersen.

“In a very tangible sense, the very reduced figures, the slim forms that you see in his work have to do with the fact that they're essential. They are the human figure reduced to its essential form, in a sense."

“Alberto Giacometti - What Meets the Eye” opens at Denmark’s National Gallery, Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK) runs until 20 May.