Larry Kramer, activist and writer whose play The Normal Heart tackled the Aids epidemic – obituary

Larry Kramer, who has died aged 84, was an American dramatist whose play The Normal Heart, an autobiographical tale of an angry young man fighting to warn the authorities and gay community in New York City of the looming Aids epidemic, represented the first serious artistic attempt to face up to the crisis.

The play caused a sensation when it opened at Joseph Papp’s Public Theatre in New York in April 1985, and in 1986 when it was staged at the Royal Court in London in a production starring Martin Sheen as Kramer’s alter ego Ned Weeks. In 2000 it was named one of the 100 greatest plays of the 20th century by the National Theatre.

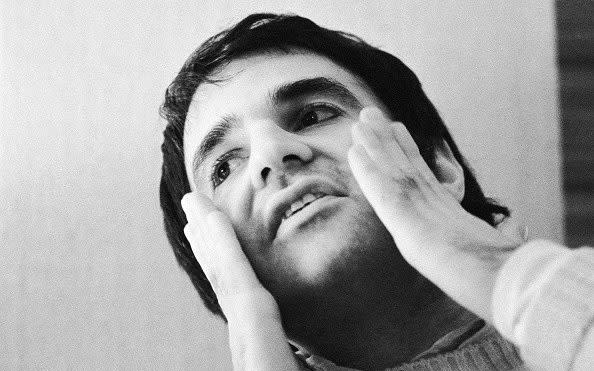

A short, neatly dressed man with close-cropped hair, Kramer became a prominent LGBT and Aids activist, co-founding the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, the world’s largest Aids service organisation, in 1982. But his willingness to put people’s backs up led to his being forced out of the group for refusing to adopt a moderate tone with New York city officials, whom he repeatedly accused of ignoring or trying to cover up the epidemic.

In 1987 Kramer founded the more abrasive direct action group, Aids Coalition to Unleash Power (“Act Up”), whose confrontational advocacy helped to keep the Aids crisis on the front pages and, arguably, spurred government and medical authorities to speed up HIV/Aids drugs research.

Yet Kramer was regarded by many in the gay community as a pariah for daring to question, in The Normal Heart and in other writings, whether the rapid spread of HIV owed something to the hedonistic “bath house” culture that developed in the 1970s.

“When are we going to admit we might be spreading this?” asks Ned. “We have simply f----d ourselves silly for years and years, and sometimes we’ve done it in the filthiest places … This is not a civil rights issue, this is a contagion issue … We know enough to cool it for a while – and save lives while we do.”

Ned Weeks cropped up again in another autobiographical work, The Destiny of Me, which took Broadway by storm in 1992 and won an Obie Award. The play showed how the seeds of Kramer’s combative fury as a campaigner grew out of an unhappy childhood.

Laurence David Kramer was born on June 25 1935 in Bridgeport, Connecticut, the second son of George Kramer, a lawyer, and his wife Rea (née Wishengrad). In 1941 the family moved to Washington.

By his own account Larry hated his father, who called him a “sissie” and contrasted him unfavourably with his older brother Arthur, a scholar and athlete: “I could never do anything right. [My father] always picked on me and yelled at me and occasionally hit me. I was a creative person whose creativity was always looked on as suspect by my parents.”

Yet in 1953 Larry followed his father and brother to Yale, where he read English Literature. It was not a happy time. A homosexual in a macho fraternity-centred institution, he tried to commit suicide. An affair with a German professor – his first sexual relationship with a man – came as a liberation.

After graduation in 1957 he worked in New York as a messenger boy for the William Morris Agency and then as a story editor with Columbia Pictures. In 1961 Columbia sent him to London, where he worked as production executive on Dr Strangelove and Lawrence of Arabia.

He also became involved in negotiations for a film adaptation of DH Lawrence’s Women in Love, but when the deal fell apart, he resigned from Columbia, spent all his own money buying back the option and commissioned David Mercer to do the screenplay. It arrived but, finding it was “altogether more Marxist than anything DH Lawrence ever considered”, Kramer wrote the script himself, and eventually took it to Ken Russell.

Women in Love, released in 1969, won Glenda Jackson an Oscar for best actress and earned three other Oscar nominations, including for best adapted screenplay. It was Kramer who persuaded the censor Lord Trevelyan not to veto the celebrated fireside nude-wrestling scene between Alan Bates and Oliver Reed.

Determined by now to become a writer, Kramer returned to New York in the early 1970s and wrote several more screenplays – and then a novel called Faggots.

Published in 1979, three years before Aids was identified, it infuriated New York’s gays with its critical depiction of promiscuous behaviour in the gay beach community of Fire Island. The book was banned from New York’s only gay bookshop and panned in the gay (and mainstream) press. Yet it went on to become a bestseller.

It was only in July 1981 that Kramer became conscious of a series of unexplained deaths among friends in New York: “People I knew were suddenly dying and nobody knew how or why; what’s more, nobody seemed to want to find out. They were almost literally burying their heads in the sand. I guess that was when gay politics began taking up more of my time than writing.”

After reading an article about cases of Kaposi’s sarcoma among young gay men – a rare cancer previously associated mostly with older men – he convened a meeting of about 80 people in his New York apartment and formed the Gay Men’s Health Crisis.

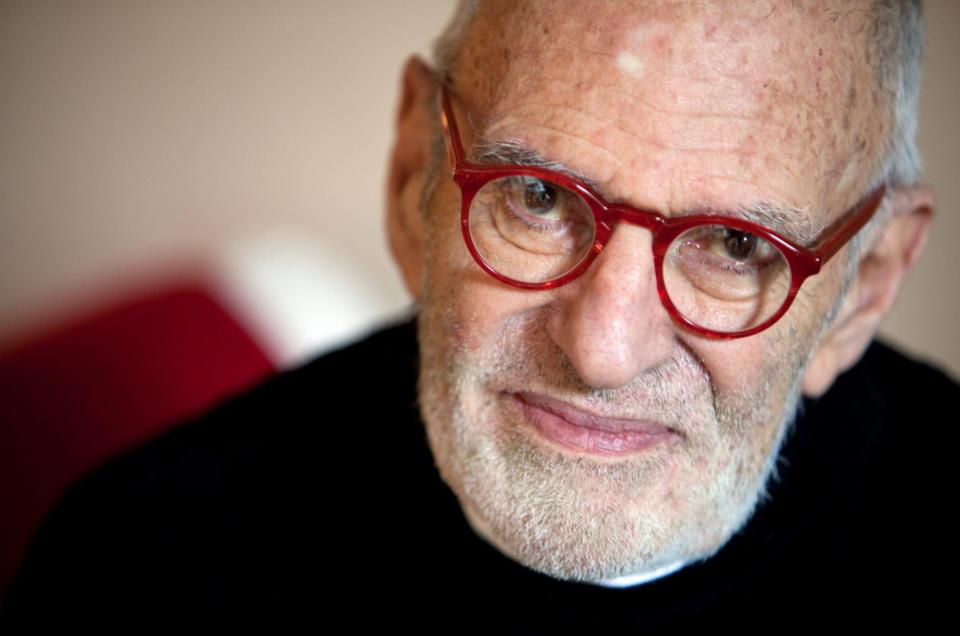

Kramer himself tested HIV-positive in 1986. As better treatments became available, however, he deplored the return of unsafe sexual practices in the gay community. “We created a culture that in essence killed us,” he told The Guardian in 1997. “It’s time therefore to admit that and to create a new culture not so sexually-centred.” Gay writers, he maintained, had cheapened the gay experience by constantly harping on about sex.

Such opinions earned him the hatred of many gays, but Kramer never minded who he offended. One of his targets was Anthony Fauci, the director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, whom Kramer attacked in 1988 as a killer and “an incompetent idiot” for not moving fast enough to release Aids treatment drugs.

Fauci was inclined to take the charitable view and credited Kramer with playing an “essential” role in spurring the scientific community to develop new treatments. In recent years the pair developed a wary friendship and, shortly before his death, Kramer emailed Fauci expressing sympathy over the criticism he was getting as the public face of the White House task force on the coronavirus epidemic: “His one-line answer was, ‘Hunker down,’” Kramer reported.

Kramer’s other publications include Reports From the Holocaust: The Making of an Aids Activist (1994), and an ambitious two-part “history”, The American People (2015 and 2020), a central theme of which was that many of the US’s most important figures, from George Washington and Abraham Lincoln to Mark Twain, Herman Melville and Richard Nixon, had had homosexual relationships. Reviews were unflattering.

His harangue against promiscuity in Faggots, Kramer once explained, arose out of bitterness at the breakdown of a relationship with David Webster, an architect with whom he had an affair in the early 1970s. They met up again in the early 1990s, however, after each man had buried a lover, and married in 2013.

Though Kramer was HIV-positive, he never contracted Aids, though he developed liver disease and underwent a liver transplant in 2001.

He died of pneumonia and is survived by David Webster.

Larry Kramer, born June 25 1935, died May 27 2020