What We Know And Can Agree On: Wikipedia At 20

Each summer, the staff of Wikipedia get together with their most fanatical contributors for a five-day conference called Wikimania, a sort of Wrestlemania for the brainy and pedantic. There is soul-searching, navel-gazing, pulse-taking and crystal-balling, not forgetting punch-pulling and verbal flame-throwing. Popular issues for discussion include: inclusion, deletion, citation, representation, notability, harassment of editors, empowerment of users, and the open source software operating system Ubuntu. Astonishingly, perhaps, the event sells out fast.

Last year the venue was Stockholm, two years ago Cape Town, and next year — celebrating Wikipedia’s 20th birthday — it will be Bangkok. (Or, next year, pandemic permitting, it will be Bangkok, the capital and most populous city of Thailand, known in Thai as Krung Thep Maha Nakhon or simply Krung Thep, occupying 1,568.7sq km [605.7sq m] in the Chao Phraya River delta in central Thailand with a population of over eight million, 12.6 per cent of the country’s population as a whole, the city designated as a “tropical savanna” in the Köppen climate classification, the capital tracing its roots to a small trading post during the Ayutthaya Kingdom in the 15th century.)

Like the textual behemoth that inspired it, Wikimania goes high and low. You turn up from all corners of the globe, get the bright yellow T-shirt, and within minutes you’re embedded in a break-out group called “Wiki Loves Butterfly”, or “Serbia Loves Wikipedians in Residence”, or “Let’s Completely Change How Templates Work!”. The conference also holds board meetings, and pledges to do better next year on issues of gender and racial diversity. It even announces its Wikimedian of the Year, a title held (at the time of writing) by Emna Mizouni, a Tunisian human rights activist praised for her work with Wiki Loves Monuments and WikiArabia.

And then, as the sky darkens, and should you have the stomach for such things, you may join the gatekeepers of the world’s knowledge as they indulge in tequila-based Wikishots and talk about their “passion projects”. You would be surprised if these didn’t include making snow globes, real-life Quidditch, “being awesome” and jail-friendly Power Yoga, at the very least.

Wikipedia is a universe unto itself, its ambition unequalled and its scale unprecedented. Its 300 staff and contractors are fond of a single phrase: “Thank God our little enterprise works in practice, because it could never work in theory”. In theory, Wikipedia should be a disaster. The work of anarchists, trainspotters, creators, vandals, world experts, world amateurs, super-grammarians, super-creeps, supremacists and lone-wolf information crackpots, many hundreds of thousands of each from all the world’s nations, every one vaguely suspicious of everyone else, some using Google Translate in hilarious ways, all battling for some sort of supremacy in a multiverse of ultimate truth — that doesn’t bode well. And yet that’s what Wikipedia is, an errant information community that continues to create something of brilliance with almost every keystroke.

Since its creation in January 2001, Wikipedia has grown into the world’s largest online reference work, attracting more than 500m page views per day and a billion unique visitors each month (who make 5.6bn monthly visits in total and hang around for an average of four minutes). It offers more than 53m articles in 300 languages, including — at 5pm on 8 September 2020 — 6,155,156 articles in English that have been subject to 972,684,694 edits. It is the world’s seventh most-visited site, sitting behind Google, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and the Chinese search engine Baidu. According to the analytics company SimilarWeb, Wikipedia is actually the seventh-equal with Czech-based XVideos, and only just ahead of Cyprus-based Pornhub. (In the UK, Wikipedia stands ninth in the charts, overtaken by eBay and the BBC. Since you’re wondering, the highest ranked porn site in the UK is Pornhub at number 13, which is just one below Daily Mail Online.)

More than any other float in this parade, Wikipedia settles arguments and ignites debate. It sends you down rabbit holes so fathomless that you emerge gasping, astonished at what other people know and consider important. Its offshoots help you with your homework (Wikiversity), your wedding speeches (Wikiquote), your journals and presentations (Wikimedia Commons), your online sightseeing and travel adventures (Wikivoyage), and your spelling (Wiktionary). The rest of it just helps you with your life, and the placing of it within contexts both modern and historical. It combines every high-brow piece of technicality with every low-brow piece of junkery. It has the track length of the fourth song on the third album by a band you’ve never heard of and never will, a list of the 74 churches preserved by the Churches Conservation Trust in the English Midlands, the complete text of Darwin’s treatise The Various Contrivances by which Orchids are Fertilised by Insects, and a biography of the mathematics teacher Riyaz Ahmad Naikoo (also known as Zubair), who was one of the top 10 most wanted rebels in the disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir.

But obscurity never overwhelms relevance. I watched in awe as its Covid-19 pages expanded in depth and sober analysis from the first cases at the end of last year to its global peak seven months later, as it diligently modified facts, trends and theories as they emerged. There was nowhere else with such a calm and comprehensive global approach, and nowhere else where the common reader could go for a comparative overview of every other deadly virus in our richly plague-ridden past. As of the end July, Wikimedia claimed that more than 5,000 Covid-19-related articles in 175 languages had been created by a collaboration of more than 67,000 editors.

You could make a strong case for suggesting that Wikipedia is the most valuable single site online, and the most eloquent and enduring representative of the internet as a force for good. It has indeed completely changed how templates work. It strives for democracy in its performance and neutrality in its effect. It is ad-free, pop-up free, cookie-free, and free. It confounds human venality and appeals to our better nature.

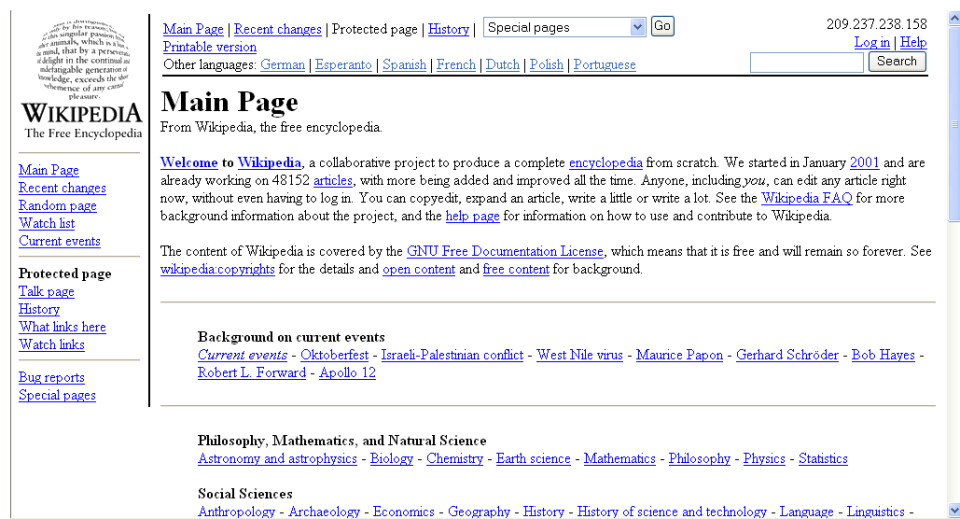

It certainly confounds its co-founder, Jimmy Wales. Wales set up Wikipedia to supplement an earlier online open-source encyclopaedia he had founded with Larry Sanger the year before named Nupedia. The problem with Nupedia was its concept: its articles were written by experts and peer-reviewed, which rendered it much too slow for mass appeal in the digital world. Wiki means “quick” in Hawaiian, and Wikipedia joined the growing number of online communal wikis already available that could be compiled and edited swiftly by anyone with a basic knowledge of digital etiquette. Everyone who contributed to Wikipedia was a volunteer, and from the start the site was governed by its contributors.

“Although I have often described myself as a ‘pathological optimist’,” Wales told me via email, “I don’t think I really understood the depth of the impact that we would have. I certainly didn’t foresee how some very early decisions against collecting, sharing, and selling data would end up setting us fundamentally apart from the sector of the internet that people are increasingly uneasy with.”

The tech-lash against Facebook and Twitter has left Wikipedia largely unscathed. Or rather, Wikipedia is saddled with many of the same sort of criticisms and shortcomings it has always had. Wales calls these “difficult questions about behaviour”.

“We are humans, and people do get into arguments, and people who ‘aren’t here to build an encyclopaedia’ show up to push an agenda, or to troll or harass. And dealing with those cases requires a great deal of calm and sensible judgment. It requires building robust institutions and mechanisms. If we were to deal with some problems in the community by allowing the Wikimedia Foundation to become like other internet institutions (Twitter comes to mind), where policing the site for bad behaviour is taken out of the hands of the community, we’d end up like Twitter — unscalable, out of control, a cesspool.”

I asked Wales what he thought of his own Wikipedia entry, which includes his nickname (Jimbo), his background in the financial sector, and his involvement in an online portal that specialised in adult content. “It’s as right as the media about me is right,” he replied. “I don’t think it mentions that I’m a passionate chef, which is a pity. But I think that’s because it’s never been covered in the press. You can mention it — that’ll set the world to rights.”

Wales is now chair emeritus of the Wikimedia Foundation. When I asked him to describe his present role in the empire, he made an unusual comparison. “I think UK audiences will understand this better than other audiences. I view my role as being very much like the modern monarch of the UK: no real power, but the right to be consulted, the right to encourage, and the right to warn.”

I wondered whether he regretted not being a billionaire like all the other pioneers on that Top 10 chart: did he never regret not monetising Wikipedia in some way? (“Just a bit of advertising,” I suggested. “Think of what good all that money could do…”)

He replied, “No, I’m content with where we are. In 500 years, Wikipedia will be remembered and (if we do our job well in setting things up with a long-term perspective for safety) still be informing the public. I doubt many of our commercial colleagues will even be remembered, much less still here.”

Writing in The New York Review of Books in 2008, novelist Nicholson Baker wrote a cute summation of Wikipedia’s early methodology. “It was like a giant community leaf-raking project in which everyone was called a groundskeeper. Some brought very fancy professional metal rakes, or even back-mounted leaf-blowing systems, and some were just kids thrashing away with the sides of their feet or stuffing handfuls in the pockets of their sweatshirts, but all the leaves they brought to the pile were appreciated. And the pile grew and everyone jumped up and down in it having a wonderful time.”

But there was a problem. Not long into adolescence, “self-promoted leaf-pile guards appeared, doubters and deprecators who would look askance at your proffered handful and shake their heads, saying that your leaves were too crumpled or too slimy or too common, throwing them to the side.”

What is and isn’t valued knowledge, and how best to present it, has been the recurring headache of every encyclopaedia editor in history. Add in the digital world’s perfectionists, elitists, sticklers and bullies, and you have a recipe for chaos. So certain policies and guidelines evolved to keep the leaf pile both useful and valuable.

While its free-form, open-access ethos still holds — anyone can contribute new articles and edit old ones — the appearance of new material on the site is subject to approval from 1,000-plus experienced “administrators”. You cannot, for example, just go in and write that your teacher or boss is a feeble-minded moron, however accurate that may be, and expect it to be hyperlinked to the site’s many other feeble-minded morons, or the history of feeble-mindedness, or the Ancient Greek derivation of the word moron. If you have some sort of published evidence, though, that’s a different matter; very early on, Wikipedia decided that it would not publish original material on its site, relying instead on information published elsewhere. Neutrality and reliability are what keeps it readable and vital.

The funny thing is, Wikipedia used to be considered a joke. When, around 2005, an editor emailed to say that he was putting together an entry on my work and would I be prepared to supply some additional information, I ignored him. Wikipedia was unreliable and prone to so much misinformation that I didn’t think it was worth being a part of.

Although many early elements were sound, large portions resembled a six-year-old’s birthday party. There are many mischievous highlights: one of the most elegant was an early article on the poodle, which remained on the site for some time and stated simply, “A dog by which all others are measured.” Nicholson Baker found incisive early entries on the Pop-Tart: “Pop-Tarts is German for Little Iced Pastry O’ Germany… George Washington invented them…”. Popular flavours included “frosted strawberry, frosted brown sugar cinnamon, and semen”.

The fact that Wikipedia is a non-profit that doesn’t track its readers (and thus doesn’t sell on readers’ information) must necessarily raise the question of how it keeps going: it has a lot of servers and engineers to maintain, as well as its staff and headquarters in San Francisco, and it has a legacy-maintaining charitable foundation to run. Part of the answer lies in an email I received recently from Katherine Maher, Wikimedia Foundation’s executive director. The subject was “Simon — this is a little awkward”, and the message, which came with a photograph of the smiling sender, was an appeal for a donation.

Two years before, I had given Wikipedia the huge sum of £2 to carry on its sterling work, and now it wanted more: “98 per cent of our readers don’t give,” Maher wrote. “They simply look the other way. And without more one-time donors, we need to turn to you, our past donors, in the hope that you’ll show up again for Wikipedia, as you so generously have in the past.” If I didn’t give again, she feared, Wikipedia’s integrity was at stake. “You’re the reason we exist. The fate of Wikipedia rests in your hands and we wouldn’t have it any other way.”

I ignored it. So a month later, Katherine Maher wrote to me again. There was a new photo of her, still smiling, but she had a darker message: the email was titled “We’ve had enough”. It explained how every year Wikipedia has had to resist the pressure of accepting advertising or selling on information or establishing a paywall, and every year they’ve been proud to resist. But “we’re not salespeople”, Maher wrote. “We’re librarians, archivists and information junkies. We rely on our readers to become our donors, and it’s worked for 18 years.” Katherine Maher now wanted another £2, although there were also click buttons to give £20, £35 or £50.

Obviously these weren’t personal emails — hundreds of thousands of others received the same messages — but I thought I’d make it personal by going to see her. Our meeting in the flesh was truncated to meetings on Zoom, which meant I got to watch her eat scrambled eggs and her partner’s sourdough in her San Francisco kitchen.

Maher is 37. Her name rhymes with car. She says she began editing Wikipedia as a university student in 2004 — an article about the Middle East which she doesn’t think survived on the site for very long. She joined the Wikimedia Foundation in 2014 as chief communications officer after a career in communications technology at Unicef and a digital rights company. Soon after becoming executive director in 2016, she encountered a problem about herself: the freshly created Wikipedia page detailing her appointment and early career was marked for deletion. “I wasn’t notable enough,” she told me. “The thinking was, ‘just because she runs the foundation doesn’t mean that she’s actually done anything of great note in the world.’” She says she loved this utterly compliant nature of the beast she was now running, although she wondered whether the debate also had a gendered element to it. The article stayed.

Our chat necessarily led to a discussion of what, after four years in the job, she would now regard as the most notable achievements of her tenure. She spoke in terms of an ongoing battle. “While Wikipedia is not a site on the internet that has really obvious issues of harassment… it is not an environment that is particularly welcoming to new people. It is not an environment that is particularly welcoming to women. It is not particularly welcoming to minorities or marginalised communities.”

She says the aggressive approach she’s taken towards those editors she sees as destructive has occasionally “blown up in my face”, not least her decision last year to ban an editor she saw as “prolific, but not productive… somebody who was driving other editors away through their behaviour”. She has upset others by her insistence that the world in which Wikipedia will operate in the future will demand large additional and alternative sources of revenue. Machine learning and artificial intelligence will require new tools that are computationally expensive. The site, though efficient, may need a complete aesthetic rethink (it does look increasingly 20th century). And the expansion into emerging communities in Africa and elsewhere will also require new resources.

When we spoke again a few weeks later, our conversation turned philosophical. “I don’t think Wikipedia represents truth,” she began. “I think it represents what we know or can agree on at any point in time. This doesn’t mean that it’s inaccurate, it just means that the concept of truth has sort of a different resonance. When I think about what knowledge is... what Wikipedia offers is context. And that is what differentiates it from similar data or original research, not that that isn’t vital to us.”

Original research is what news organisations push out every single day. Maher mentions a YouGov poll from 2014 that found Wikipedia to be more trusted in the UK than the BBC. “I think for a lot of companies, they would say, ‘That’s wonderful, we beat our competitors’. My response was, ‘First, the BBC is not a competitor. And second, that’s not wonderful at all.’ If there’s a trust deficit with the sources that we rely on then ultimately that deficit will catch up with us as well. We require that the ecosystem be trusted.”

Maher calls herself an inclusionist, arguing against those who wish to keep Wikipedia on a high intellectual footing, reasoning that anything that involves a learning journey is beneficial. “If we don’t have your Bollywood star, or pop singer, then you’ll come to us and you’ll bounce right off, because you don’t see anything that’s relevant to your life.”

She says the people who are most excited to meet her are the ones who use Wikipedia every day; but the ones who give her frosty looks are those who have the highest public profile. She recalls sitting next to two distinguished female scientists at a recent conference. “I introduced myself, and very often in a context like that it’s, ‘Oh, another woman who’s going to be a speaker and that’s fantastic’. So I say I run the foundation that runs Wikipedia. And the first thing I heard was, ‘we don’t like our articles’. One of the things they reflected on was, ‘Look, my body of work has changed dramatically since the article was first written, and it hasn’t kept up to date with my newest thinking in the area.’ And that’s a very legitimate concern.”

But at least they had an entry, which was not the case with Canadian scientist Donna Strickland. On 2 October 2018, Strickland was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for her work on chirped pulse amplification, something that may have a direct bearing on the future of eye surgery and other medical laser applications. But good luck trying to find more information on her on Wikipedia the day after the announcement. Her absence became a cause célèbre. There had been an entry prepared about her, but it was rejected on the grounds of insufficient references from secondary sources. That is to say, because she was only famous in the world of physics, and had not previously been written about in the popular media, she then couldn’t be written about in the world’s most popular encyclopaedia.

No one was keener to point out the anomaly than Maher. Soon after Strickland’s entry finally appeared, Maher blogged that as of the beginning of October 2019, only 17.82 per cent of Wikipedia’s biographies were about women. She is proud that women gather frequently for day-long editathons to improve this figure, and flags up the site’s recent focus on improving and expanding articles concerning women’s health and the history of the black diaspora. This is not merely a worthy ambition; it’s regarded as crucial to Wikipedia’s global standing. Maher has a neat phrase for another cultural imbalance: “Too many articles on battleships, not enough on poetry.”

Conversely, Maher says there is a “whole industry” based upon changing existing Wikipedia profiles from people who don’t like what’s written about them. It’s considered “black-hat editing”, and the community really gets upset by it. “We encourage people not to do it, because usually you’ll get caught, and when you do get caught whitewashing your own Wikipedia page it’s not a good look. We always tell elected officials this.”

Recently, even Boris Johnson seemed to grasp the difficulty. In June, referring to the destruction of statues of dishonoured men, he columnised thus: “If we start purging the record and removing the images of all but those whose attitudes conform to our own, we are engaged in a great lie, a distortion of our history, like some public figure furtively trying to make themselves look better by editing their own Wikipedia entry.” Am I the only one to read this and think he was writing with bitter experience?

Between our two chats, Maher had attended a Zoom board meeting that sounded like every other institutional board meeting in history: performance reviews, financial shortfalls, expansion or the lack of it. But then there were more specific issues: how to celebrate Wikipedia’s 20th anniversary in January, and continuing discussions about the impact of small screens on people’s ability to absorb content and make edits. Does this inevitably mean less deep reading, or does it vastly increase accessibility? Both. Between March and May 2020, 43 per cent of users accessed Wikipedia on a computer, and 57 per cent on a phone.

Wikipedia’s mobile app is a fascinating thing in itself, not least its information randomiser. This is an addictive lucky dip through millions of its pages: you click on a dice symbol and you get a nice way to spend a minute or a day. When I last tried it at the end of June it threw up the following, in the following order: Peters’s wrinkle-lipped bat; roads in Northern Ireland; Eddie Izzard’s Live at the Ambassadors video; proper palmar digital nerves of median nerve [nerves in the palm of your hand]; Vincenz Fettmilch [early 17th-century gingerbread maker]; Herman Myhrberg [Swedish footballer who played in 1912 Olympics]; list of Guangzhou Metro stations; Hand Cut [1983 album by Bucks Fizz]; methyl isothiocyanate [chemical compound responsible for tears]; and Lusty Lady [defunct peep show establishment in Seattle which once boasted a marquee wishing passers-by “Happy Spanksgiving”].

The encyclopaedia is a concept dating back to the ancient Greeks. Many of Wikipedia’s earliest entries derived from an out-of-copyright edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica, the institution that began in 1768 and produced its last physical set in 2012. Britannica still thrives as a learning resource online, where its in-depth “premium” knowledge (ad-free and written largely by scholars) costs £65 a year. Compared to the 16.83bn visits made to Wikipedia between March and May 2020, britannica.com attracted 124.7m; though tiny in comparison, the figure is far larger than the number of people who ever consulted its print edition.

In print, Encyclopedia Britannica was hefty, daunting and seemingly definitive, the revered pinnacle of human knowledge. Every school and public library had one, and if its zealous salesmen had anything to do with it, every conscientious home with ambitious parents had a set too (along with its supplementary yearbooks; just when you thought you had paid your last monthly instalment, along came one of those). The cost of its 32-volume, five-yard-long set in 2012 was £1,200.

Its Zen-like spines (Excretion — Geometry, Geomorphic — Immunity, Metaphysics — Norway) perfectly defined its purpose: here was everything under the sun, and every time you picked it up you were reminded of not only how much you didn’t know, but also how much you would never understand. I grew up within that classic generation: Britannica was a worthy and burdensome presence in our living room, the benevolent, wide-bodied uncle who was rarely consulted but refused to leave.

Like all printed encyclopaedias, Britannica had obsolescence built in. Humanity just wouldn’t sit still: four days after the copyrighting of the first printing of the 14th edition in September 1929, the US stock market began its perilous fall, heralding the cataclysmic global depression. A subsequent printing of the same edition appeared just too late to mention the election to the chancellorship of Adolf Hitler. Another edition was published in the same month as Germany invaded Poland. And the edition printed on thin Indian onion paper in July 1945 narrowly managed to miss the dropping of the first atomic bombs.

You probably don’t need to be told that future mint editions would arrive on the doorsteps of homes, schools and libraries just weeks before Sputnik and just days before the first moon landing. Some would call this extremely bad luck, others might posit a jinx. To Britannica’s credit, the editor of the 1973 edition acknowledged these shortcomings with a gallant sigh: the world had a habit of advancing faster than the printing press.

Wikipedia does not have this problem. Someone notable dies and the cause of their passing is on the site before the funeral. Its “live” coverage of Covid-19 involved tens of thousands of edits in the first month. Innocent mistakes and deliberate mischief tend to get caught and corrected on Wikipedia with impressive speed these days, either by bots or humans. Jimmy Wales told me that while misjudgements are still made, and verbal terrorism occasionally prevails, the site is very far from the anarchy some people assume. You edit in something “hilarious” about a famous person or important topic and it is unlikely ever to appear on screen. Even obscure corruptions don’t hang around for very long.

Not so Britannica, of course. For all its stellar contributors — Hitchcock on film production, Houdini on conjuring, and Einstein on space-time (pretty chewy reading that one, no matter how he simplified it for the dummkopf) — there were many occasions when its less well-known experts just got things plain wrong, or plain weird, and occasionally grimly racist, particularly in its earliest editions, and the evidence is there for ever more. How best to treat tuberculosis, for example? “The most sovereign remedy... is to get on horseback everyday.”

Childhood teething could, the encyclopaedia assured, be treated by the placing of leeches beneath the ears (as with medical textbooks of the period, leeches cured everything). The ninth edition, published volume-by-volume between 1875 and 1889, advised its readers on how to become a vampire (get a cat to jump over your corpse), while 30 years later its 11th edition found werewolves among “the people of Banana (Congo)”.

I looked up “people of Banana” on Wikipedia and found this: “The page ‘People of Banana’ does not exist. You can ask for it to be created, but consider checking the search results below to see whether the topic is already covered.” The search results included banana, banana republic, banana leaf, banana fish, banana ketchup, speech banana, Banana Yoshimoto and everyone’s favourite, banana bread.

So I asked for “People of Banana” to be created. I prepared my entry: “‘The People of Banana’ is said to be one location where you may find werewolves.” I cited “Entry on Werewolves, Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition (1910–’11), as referenced in Britannica’s special 250th anniversary collector’s edition, 2018”.

I didn’t hold out much hope. My submission joined 2,160 other pending submissions, 114 of which had been waiting five weeks for a Wikipedia administrator to approve or dismiss them (other recent submissions included items whose titles I didn’t understand: “Dog Puller”, “IBTS Greenhouse” and “Bug Music”).

My administrator would probably dismiss my People of Banana entry on the grounds it did not pass muster. “There is a very good chance that the topic is not notable and will never be accepted as an article,” the guidelines inform me. Other reasons why my entry could be rejected were divided into 34 sub-categories, including “declined as copyright violations”, “declined as a non-notable film”, “declined as jokes”, “declined as not written in a neutral point of view” and — the ultimate — “declined as not suitable for Wikipedia”.

But then, with almost all hopes dashed, I found that I had mis-searched, and a place called Banana in the Democratic Republic of Congo did indeed have its own entry, albeit a tiny one. There was no mention of the people of Banana specifically, and none of werewolves, but I learnt that Banana was a very small seaport situated in Banana Creek, an inlet about 1km wide on the north bank of the Congo River’s mouth, separated from the ocean by a spit of land 3km long and 100–400m wide.

The article, like all articles on Wikipedia, was accompanied by its own “History” page, a

behind-the-scenes catalogue of the edits that had made the page accurate and compliant, and attuned to house style. Often, these “making of” comments are more fascinating than the article they scrutinise. In this case, a Danish contributor called Morten Blaabjerg — one of relatively few to use a real name (other editors on this Banana page plumped for Warofdreams, Prince Hubris and Tabletop) — added the “Henry” to “Henry Morton Stanley” (Stanley used Banana as a starting point for an expedition in 1879).

That edit was made in July 2005. The page had received relatively few edits since its inception the year before, although for a short while in 2007 there was a nice little hoo-ha over whether Banana was a seaport or a township. As far as Blaabjerg goes, we learn that he now lives in Odense, but was born in 1973 in the small Danish town of Strib, near Middelfart.

Wikipedia is a very live thing. That is its beauty; it is humanity in all its forms. The project will not be finished until we are all finished, or until something destroys Wikipedia’s servers in San Francisco, Virginia, Texas, Amsterdam and Singapore, and all its mirror sites globally, and then possibly the entire internet and our ability to rebuild it.

The people concerned with Wikipedia’s security take their roles reassuringly seriously, for they realise how much may be at stake if they do not. When it began 20 years ago, its existence could not possibly have seemed so important. Its custodians are also rightly concerned with its future, and the future of how we obtain and comprehend information as we evolve. Katherine Maher talks of “the integration of structured information with unstructured knowledge”, which will allow us to enter a new, concentrated world of learning.

“I always think of Wikipedia not as an encyclopaedia. It’s an information ecosystem. And so when you actually have that connected and linked together, it doesn’t just offer possibilities for Wikipedia as we think of it. It also means that we can connect all of those concepts out to any other information ecosystem that exists and links out into the net,” she says.

“The Library of Congress links out to the great museums of the world and links out to movie studios. That to me is the vision of the future. It’s how you actually build and knit together the world’s knowledge.

“You know, with Wikipedia, it’s merely a protocol. It’s a reference point, a place that people know has been doing this work already. How do you expand that outwards so that others can join in, getting all that knowledge together around the globe? So there’s just always going to be more to do.”

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts

You Might Also Like