I Kept My Childhood Shame A Secret For Years. Now It's Time To Be Honest About Who I Really Am.

Scrolling through Instagram recently, I stopped on a post. It was meant to be a joke — a word intentionally spelled the wrong way and its meaning misinterpreted because the person posting it supposedly had dyslexia. In the comments, someone said, “As a teacher, I find this exceedingly humorous!!!”

I didn’t find it funny at all.

You probably wouldn’t either if you had spent most of your life trying to prove a stereotype wrong and still found yourself unexpectedly becoming the butt of jokes. It doesn’t take much to discover what the average view of dyslexia is — a quick Google search for “memes about dyslexia” will provide various examples.

And it isn’t just online. Over the years, I’ve been in more rooms than I can count where some unknowing person made an offhand comment about being dyslexic. They used it as a way to describe themselves or someone else when they made a mistake, fumbled through something or had an off day, with remarks like “They’re having a dyslexic moment” or “I can’t read today, I must be dyslexic.”

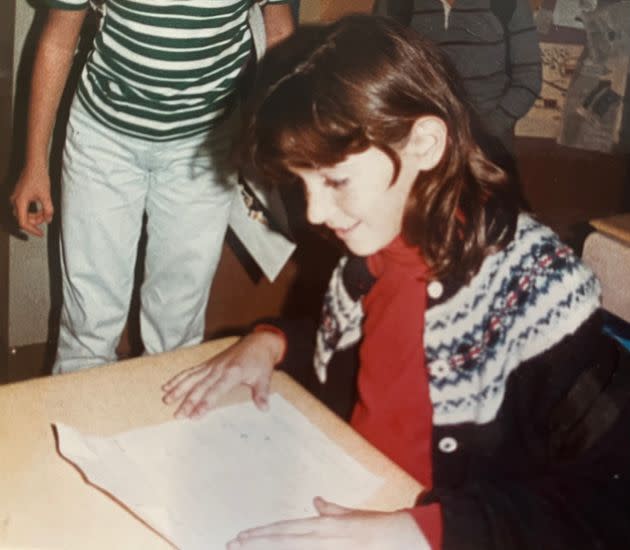

I was diagnosed with dyslexia in the third grade. As a child in the 1980s, I was labeled “stupid” and “slow.” I was told that my diagnosis wasn’t real and that I just wasn’t trying as hard as the other kids. I remember the shame of being pulled out of “regular” classes to go to the resource room (where it was known “the dumb kids” were sent).

I spent years in school fighting to get into classes I believed I deserved to attend despite my learning disability. I wasn’t encouraged to do so by teachers or administrators. Having children with learning disabilities in classrooms often means more work for the teachers as well. It’s easier to push those kids through school by keeping them in the lowest-level classes and shuffling them off to a resource room. Once I got myself into higher-level classes, I often had to work harder than the other students just to stay there.

Although it’s been decades since my days in school and the cultural perception may be that we have come a long way, I’m not so sure how much things have really changed. Seeing posts like the one on Instagram, met with comment after comment of laughing emoji, makes me believe we still have a lot of work to do on how we view people with learning differences.

Children with learning disabilities often feel like their brains don’t work “correctly,” believing that there is something about them that needs to be “fixed” and they need to learn the “right” way to do things. Often, the first thing a child feels after they are diagnosed is shame.

That spurs a need to conceal the disability, which is often carried into adulthood. As a result, once a person learns the accommodations they need to navigate the world undetected, they may rarely talk about their learning differences again.

For years I knew there was a lot of misunderstanding about dyslexia, but I stayed quiet because I feared my work would be judged differently if I told the truth. I’ve come to see that by doing this, I was part of the problem — because if people like me don’t speak up, the perception will never really change. I now feel a responsibility to be honest about who I am (and who I was back in school). Children should know that they aren’t defined by their learning differences and, in the long run, there may be positives they don’t even know about yet.

There is no cure for dyslexia, but it has nothing to do with a person’s intelligence or desire to learn. It is a neurodivergent condition in which the brain works in a different way than the majority of other brains. “Dyslexia is a learning disorder that involves difficulty reading due to problems identifying speech sounds and learning how they relate to letters and words,” writes the Mayo Clinic, noting that it’s “a result of individual differences in areas of the brain that process language.” This leads to trouble learning new words and issues with forming words correctly.

You may wonder what people with dyslexia see when they read. Are all the words backward? The answer is no. People with dyslexia do not have a vision issue; they see words the same way that everyone else does. The difference is how they process and decode those words. And although dyslexia is not a condition that people outgrow, as we age we gain more skills to compensate for the differences.

How might this play out in real life? In a recent meeting, I was reading aloud from a sheet of paper. I got through the first few sentences without a hitch but suddenly came to a word my brain knew but my mouth simply couldn’t pronounce. The word was “spirituality,” which I have said innumerable times without thought. And yet there I was staring down at it, and as hard as I tried, it just wouldn’t come out. I stammered and then did what I always do when this happens — I made a little joke to divert everyone’s attention. (I’m good at that.)

Even though this doesn’t happen as frequently as it did when I was younger, it was not a stand-alone incident. In fact, I’d say it happens once or twice a month, usually on days when I haven’t gotten enough sleep or am particularly stressed. Sometimes I can’t think of a word. Sometimes pronouncing new names and remembering how to say them is challenging. Sometimes I say a similar but incorrect word in place of another. Recent examples of that are “grazing” instead of “gazing,” and “antidote” instead of “anecdote.”

Do I know what the words mean? Yes. Could we have the same conversation tomorrow and I’d pronounce them correctly? Most likely. Do I wish I could say your name on the first try? Of course. I can also almost guarantee that if I were writing these words, I would select the correct version. How do I know this? Because despite my dyslexia, I have been a professional writer and editor for 25 years, so I’ve had a lot of practice.

I chose this career because I love reading and writing, but I’ve always felt like I had to prove I could do the job just as well as someone without dyslexia, even if no one around me knew I was dyslexic. The reality is, the real world doesn’t have accommodations or modifications. You do need to learn strategies to help you navigate the same landscape as everyone else. As a 50-year-old woman who has worked successfully in what may be considered an unlikely career for someone with dyslexia, I think I’ve proved myself to be just as capable as many people with “typical” brains, if not more so.

These days, I am happy to talk about the challenges but I also make it a point to focus on the things about dyslexia that make me better at my job. People with dyslexia excel in narrative thinking. They have strong long-term memory, particularly when it comes to experiences and visual information. They are creative and often have strong interpersonal skills and empathy. As a writer and writing instructor who specializes in memoir and personal essay, these traits make me the perfect fit for my job.

Even though my learning difference initially posed challenges for me, I would never change my dyslexic brain. Shedding light on this aspect of myself allowed me to see that there was never anything wrong with this part of my makeup, but there was something wrong with the way I perceived it. Instead of trying to erase this part of myself, now I choose to embrace it.

Darcey Gohring is a full-time freelance writer and editor based just outside New York City. As a writing instructor, she specializes in personal narrative and memoir. Her essays have appeared in dozens of publications. She was a contributing author for the anthology, Corona City: Voices From an Epicenter. Darcey has served as a keynote speaker for writing events all over the United States. To learn more, visit darceygohring.com.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch at pitch@huffpost.com.