Karen Russell: "There's No Going Back to Normal. There Was Never Any Normal to Return To."

In Karen Russell’s Sleep Donation, set in the not-so distant future, a public health crisis has ravaged American life as we know it. Hundreds of thousands of Americans have been afflicted by this mysterious epidemic, with the nation fragmented into regional locuses of varying turmoil; meanwhile, a cure remains elusive. Television has become “a glum Hall of Prophets,” where “professional Cassandras” spread dangerous misinformation about the origins of the virus, pointing fingers at climate change and soul-sucking smartphones. With the government and the scientific establishment coming up empty-handed, the fate of the nation rests in the balance.

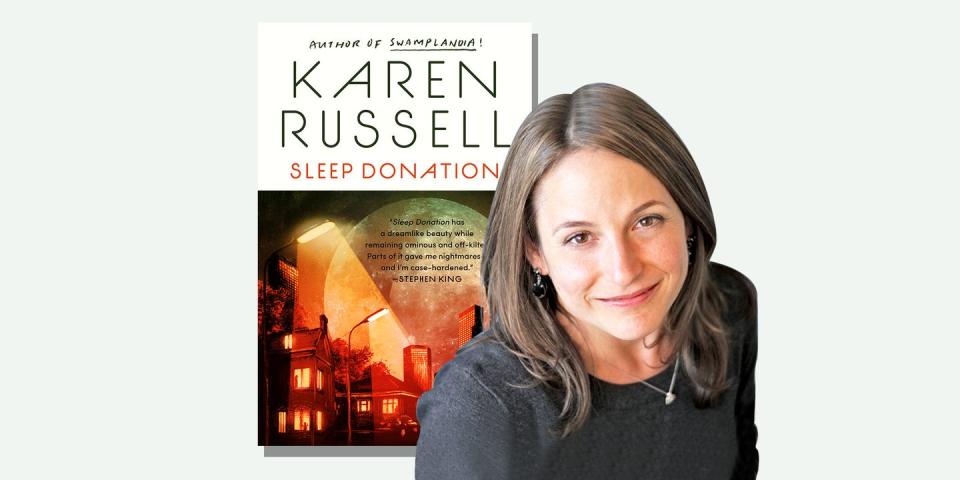

Sound familiar? Russell wrote Sleep Donation over half a decade ago, yet her nightmarish vision of a nation keelhauled by an insomnia epidemic now registers as shockingly prescient. Originally published as a digital-only novella, then scrubbed from the Internet, Sleep Donation is back and more relevant than ever (you can read the first 22 pages here at Esquire). Russell, of course, needs no introduction—the Pulitzer Prize nominee and author of five celebrated books is a literary luminary, with the finest imagination in contemporary fiction. Sleep Donation is Russell at the height of her formidable powers, at once an eerie evocation of a country whose sins have come home to roost, as well as a deeply personal story of grief and terror.

From her home in Portland, Oregon, where the landscape has been ravaged by wildfires, Russell spoke with Esquire about the frightening prescience of Sleep Donation, the challenge of writing while living through history, and the radical hope she feels about the way forward.

Esquire: Where did Sleep Donation begin for you?

Karen Russell: It was maybe half a decade ago, so I was in a very different place. I was a single woman and I suffered from insomnia. I was up on that euphorian gangplank, and I had an assignment to come up with imaginary inventions. I wrote about a Red Cross for insomniacs, because that was my dream at the time. I often thought, "God, I could use a sleep donation." Wouldn't it be great if you could just download good dreams and good sleep to insomniacs? I loved and still love giving blood—it felt so direct and straightforward. One of the few actions you could take that could potentially save a life.

I was also thinking about this circulatory system where we’re all plugged into our global society. It's just this porosity of dreams and nightmares and technologies. This was 2014, so not that long ago, but I think it's only become more acute, the ways we're all wired to one another. I was really interested in the idea of going viral. What if a nightmare could operate like a virus? What if there was this epidemic of sleeplessness, and it was possible to donate sleep to an insomniac?

What seems relevant to me right now is misinformation. All of these rumors spiraling in the wake of this new epidemic, where the national sleep supply becomes contaminated by a nightmare. This underworld of conspiracy theory, paranoia, and delusion gets me thinking about this time we’re living in, where there's a real public health crisis tormented by all the misinformation out there. Many things that felt like hypothetical fears and anxieties to me, even just a few years ago, are facts now.

I'm inside my house today because the smoke is so bad. The air is so unhealthy here. It was so hazardous last week that we didn't even leave our house for nine days. The air in our daughter’s nursery was so toxic that she had to sleep in the basement. There was nowhere we could go, because there are fires all around us. There's also the pandemic. I feel very viscerally aware of how we're all connected, how we have this economy that requires unregulated growth, and then you see what the consequences are. You push nature to the brink, you push humans to the brink, and this is what happens.

Many people I know have a kind of nostalgia for the world before 2016. But the conditions for these present emergencies were well underway at that time. We had environmental catastrophes. We knew we were headed toward climate emergencies. We knew we had this broken, for-profit health care system. We knew had a media empire with financial incentives to keep people glued to screens filled with distorted information. But there’s no going back to normal. There was never any normal to return to, so we're going to have to figure out a way forward. I hope that this is the pendulum rattling back so that we can swing somewhere else in 2021. I hope that we can make a leap into a different reality.

ESQ: Revisiting Sleep Donation six years later, seeing how shockingly relevant it’s become, how do you feel about those surprising connections between fact and fiction?

KR: I can't believe it. There’s always the vertigo of reading something you wrote that long ago. Who wrote this thing? Right after my daughter was born, a little over a year ago, I was working on Sleep Donation again and tuning it up, adding what I thought at that time would be a playful bonus track. The designers and I were looking at the CDC website, looking for brochures to riff on. It was very confusing to go from emailing these wonderful artists links to the CDC for inspiration, then suddenly, what felt like days later, we were all going there to get information. Nothing has prepared any of us for this time. Art was the only dress rehearsal we had.

ESQ: Why did Sleep Donation have to be a novella, as opposed to a novel or a short story? What appeals to you about this uncommon and under-appreciated form?

KR: The word “novella” sounds so goofy, doesn’t it? I found it even goofier the first time around, because it existed in a digital-only format, so I would tell people that it was an e-novella. No one knew what to do with that. So close to Cinderella or e-cigarette. It was a real conversation stopper. I didn't think this was going to be a 3,000 word Calvino-esque vignette about this goofy new technology, some sort of Twilight Zone meditation on the borderlands between waking life and sleeping. Books are your original dream donation technology. What does it mean for a dream to move from one body to another?

The momentum of Sleep Donation surprised me. At a certain point, I thought this would be a Swiftian satire about stealing sleep from babies and literalizing what's happening in our economy, where we steal the dreams of children and corrupt the future of an entire generation. I thought maybe I could write something humorous about that. Then it got weirder and darker and more earnestly anguished, but it never felt to me like it had the rhythms of an entire novel. It was so closely focused to this one woman in her private grief and terror. I wanted to have the world-building you can do in something longer than a story, but I also wanted to keep the camera tight on this particular person as an access point to this world of cascading horrors.

Right now, it does feel like every twelve hours, there's another crisis. It’s a domino rally of misfortunes. In this novella, I wasn’t confident that they would succeed at keeping sleep and dreams from becoming commodities. It started out as a donor system— a precious commodity with a bottomless need. Yet another finite resource of our planet. Now more than ever, I’m troubled by these questions. What do we really owe one another? What exactly is a gift? What are the conditions to keep a gift from becoming something that's coerced? What's the line between exploitation and a simple request? How do we avoid turning something that should be a birthright, like clean air or water access to nature, into a pay to play luxury?

I was just talking with my husband. We're both self-employed right now, and we were worrying that the ACA would be repealed. I know so many people in much more dire circumstances, so I think the questions in the book are so real to me. The idea of having to make a choice with potentially cataclysmic implications, and doing so in a total vacuum of information, really not knowing what the outcome would be, but having to decide what the right thing to do was… it’s so childlike in those terms, but I do think that that's that task ahead of us. Deciding what your principles are and acting in a total void of information about what the future will be, while also staying awake to your own motives.

There’s a whistleblowers hotline in this book, and I was thinking that I wish I could install a whistleblowers hotline in my own body. I wish that my best nature could lodge a complaint or blow the ref's whistle on whatever cover story I’m working on to justify my own worst behavior.

ESQ: Karen, that’s a story premise right there. That’s a short story just waiting to be written.

KR: The Being John Malkovich Whistleblowers Hotline? I need one for stress eating, I think. During our nine-day incarceration in the basement, I actually did a lot of recreational eating. It's been hard to know what meal or time it could be through all the smoke, so, we went on a vision quest. We did a lot of Elmo dance parties. It was like those German blackout clubs. We did our pre-school version of that and did the Elmo Slide for nine days.

ESQ: You’ve alluded to our current media climate, which is so vividly evoked in this novella. You call cable television a “glum Hall of Prophets,” peopled by “professional Cassandras.” Does the way you characterized the media climate when you wrote this in 2014 seem rather prophetic now?

KR: It does. In the immediate wake of Trump announcing that this was a national emergency, so much ink was spilled right away, with the media making all kinds of dire predictions. What is this going to mean for the rest of time? How is this going to change the way that we socialize forever? I've been thinking so much about that impulse to jump out of the messy present and make these proleptic leaps. I wrote some stuff back in April that already seems so dated. It's already embarrassing to see how little I knew about what this might mean and what was coming. Part of the problem with our media landscape is that it’s so driven by the market. That pushes things to feel more and more extreme.

Every time I look at my push notifications, I feel so sad for our world, but it’s also hard to know the exact truth, and to know how seriously to take some of these apocalyptic predictions. I have a scientist friend who tells me that there’s just not enough data. We’ve done such a bad job of predicting what the future might hold. Then again, maybe that’s a hopeful thing. The future is really an unknown—it’s up for grabs, and we can still alter it.

ESQ: We also don’t have to submit to this worst-case scenario mindset. Sometimes when I go down that mental rabbit hole, I remind myself that any situation could have thousands of outcomes, and I feel lighter.

KR: It could be a thousand outcomes! I’ve found it exhilarating to see how quickly everybody pivoted. Everybody felt whiplash during that brief period where it was possible to be a doomsday prepper while also drinking mimosas outside with your friends. You could go from the grocery store, where you'd just stockpiled toilet paper, directly to brunch, where you could hug your pal with no contradiction. But people very quickly changed their behavior in these profound ways. When we deem the stakes high enough, we can swerve together. We can live in a radically new way. It was the first time in my life that I've seen that kind of massive change overnight. I had a similar reaction to the protests, with millions of people on the streets here in Portland. This call for justice couldn't be ignored. I'm a big believer in collective action. If there’s a way for us to process what the stakes truly are, maybe we'll be able to move more quickly than has seemed possible in the past.

ESQ: In that same passage about the media climate, you write, "According to these professional Cassandras, sleep has been chased off the globe by our 24-hour news cycle, our polluted skies and crops and waterways, the bald eyeballs of our glowing devices." What keeps you personally awake at night?

KR: I'm really addicted to my phone. I’m helpless against it. If I don't charge it, if I don't have it, I feel like Sandra Bullock in Gravity, shooting through the void alone. There are wonderful things about being networked the way that we are, but I think the algorithms are frightening. If you, like me, list in a dark direction, and you click on a very gloomy news story at 4:00 AM, somehow your entire feed shifts, and suddenly you're on a diet of steady nightmares. That’s a real danger for me. I'm sometimes drawn to the scariest story, and I know it must be happening to other people who share this low immunity to darkness. With QAnon and other conspiracies, I assume this must be what's happening. There's this self-reinforcing loop, where the walls are closing in on people and they're being fed a diet of more and more extreme nonsense.

When I can’t sleep these days, it’s because I worry so much, especially with these fires. It’s been a real shock to our systems. I want to hope that we can do more—something as massive as a Green New Deal. It's very sad to see all the benchmarks we've totally failed. I don't think that this pandemic or these fires are one-offs. It feels like this might be a precedent instead of a freak occurrence.

When I do sleep, I keep having the same boring nightmares. Everybody has those dreams where they’re running for their lives. Sometimes I find that exhausting even in dreams. I’m like, “I have to defend my life again? God, I just did so much laundry. Can’t I just win the lottery or something? Can a nice house guest call? Does it have to be another Mad Max race through the desert of my mind?”

ESQ: As you revisit Sleep Donation in this surreal context, is there anything happening in the world that leads you to think, “This is truly stranger than fiction. Even I, Karen Russell, master of the fantastical, could not have dreamed that up.”

KR: 2020 has outpaced my imagination in every way. We abandoned our car in Texas early on and flew home with our kids. A friend of mine drove our car back. Every text from him was something like, “I’m driving through the fires. There goes that MAGA parade. The road is shut down because of all the smoke.” Recently we woke up to an orange sky. I grew up in Miami, so we had hurricanes and plenty of other natural disasters, but this felt like a very manmade disaster. The orange sky and these tremendous winds. It felt like a disaster accelerating in such a literal way, and that shocked me. Seeing all the suffering in Oregon and the speed with which these flames consumed over a million acres—that felt like something that I could never imagine. This feeling that the sky itself was falling… I can't recommend it. My son was convinced that the sun had turned into an asteroid. We had a big debate about it, and I have to admit that he won.

ESQ: A lot of writers have reported feeling unable to create during this time. How have these six months affected your own creative process?

KR: I'm embarrassed to say that I’ve had a really hard time, especially because we have more resources than so many people. I'm very lucky that I get to be home with my two kids right now, even if I might have destroyed my brain with too many repetitions of the Elmo Slide. I might have done permanent damage with that and "Ninja Rap," by Vanilla Ice. I think I'm the same age as Vanilla Ice now, speaking of things I couldn't have imagined. To be headed towards AARP with Vanilla Ice… that doesn’t feel good.

Writing has been tough, because it requires a sustained focus to enter into an imaginary world. I think we're all living under such a low sky of anxiety right now, so that's been hard. I’ve been desperate to read, because reading has felt like such a balm. When I can't find the on ramp into my own imagination, it's been wonderful to have short stories. Short stories are the perfect length to escape into another mind and live there for a little while. Then I inevitably get Bruce Willis blasted out by my kids. We all need friends right now. I feel lucky to have this giant bookshelf, because all my friends are here.

ESQ: Glennon Doyle recently said, “There are times for creating and times for becoming the person who will create the next thing. For many of us, this is a becoming time.” I like to think that the reading is part of the becoming.

KR: Glennon! I hope she’s right. I was just part of this project that The New York Times did, The Decameron Project, where a bunch of writers wrote flash fiction with the coronavirus as a backdrop. It much more challenging than I expected. I wrote a piece about a bus driver here in Portland, helming this bus and having a metaphysical accident on the bridge, where she gets stuck in time. The only thing I could write that felt in any way accurate to this crisis in progress was about how dysfunctional time feels. We’re all caught in the glue of a nightmare together, which brings me back to Sleep Donation, and to this character who's straining her eyes through the fog, trying to guess at what the future might be.

I really feel like we're all stranded in the fog together right now. We're going to get very different kinds of artistic recreations of this moment later, I'm sure, when people have metabolized it. I loved reading that issue, seeing the funhouse mirror refraction of the present moment, but I think it will be awhile before we have the perspective to really mill the coronavirus and all the disasters of 2020 into longer works of fiction.

ESQ: When you and I spoke about Orange World last year, we talked about the power and the necessity of radical hope. Certainly 2020 is a different year than 2019, but what gives you radical hope, these days?

KR: I'm talking to you in our basement, and I'm listening to my kids play on the floor above me. That seems a sentimental answer, but it's a true answer. I love seeing these kids come to this world with so much joy and enthusiasm and delight. That gets jack-hammered out of us very quickly, but it’s the way everybody shows up to this planet.

The Squad gives me hope, too. I love seeing this next generation of leaders who are prioritizing racial justice and the climate, and who have such badass progressive politics. The protests really touched me, and I think exposed a cynicism that I didn't know I possessed. To participate in them was wonderful—to feel this tidal force demanding change. For all of the things that are really dire, these times have provoked such incredible countervailing winds. I’m as scared as we all are about this election, but every person I know is working to mobilize voters, or volunteering, or somehow right on the front lines.

There was this period where I was lulled to sleep, or into a kind of lazy optimism. Now for all the pessimism, there's so much energy out there, so much urgency, and people are doing the work locally. We’re seeing this massive collective effort to change the conditions of our reality. In the early weeks of the coronavirus, watching everyone change overnight to adopt a new way of interacting to protect one another… that’s a proof of concept that it doesn't take decades to radically change. When we think the stakes are high enough, we change. I hope that we can keep flocking together and change direction quickly.

For better or for worse, we really are one body. It’s weird to be thinking of yourself as a vector for contagion, but it brings home that of course we're profoundly interdependent, and our futures are linked. There's no way to partition your life and happiness and fate from anybody else's. I think that has been so visceral for so many of us during this period. We won't forget that. It’s a new lesson, one that I hope feeds a new urgency.

ESQ: I hope we don't forget it. Not to be a professional Cassandra, but often we’re quick to fall back into the sway of our worse angels.

KR: I’m certainly fearful of that. We're all such amnesiacs, I think so much of the drama of Sleep Donation was about the simple and effortful task of staying awake. Staying vigilant is not easy. I want to try to write something—then we’ll talk again under a different administration, breathing clean air, living in a time where we’ve translated the dolphins and they're all saying, “We forgive you.” By the way, have you had any good dreams, lately?

ESQ: I’m sad to say that I usually forget my dreams, unless they scare me awake.

KR: I’ve been thinking about that. Seems unfair, doesn’t it? If we're going to be doing these dress rehearsals at night, why can’t it be a fun party? A unicorn comes out of the glen and tells you the secret of the wind. Why does it always have to be so dire?

I’ve been thinking about that because my son has started claiming to remember his dreams. Some of them sound totally terrifying. Watching someone in the grip of a nightmare where you can’t witness and you can’t intervene—that's painful. We talk a lot about genre on a continuum of fantasy and realism. When you think about the most normal person you know, and you think about what that person is likely dreaming at night… that gives me hope, in a confusing way. We're all underestimating each other so much of the time, and we're all so much weirder than you might ever guess. As a super weirdo, I find that validating. You couldn’t ever guess from your conversation across the fence what kind of universe lives inside your neighbor, or what sort of phantasmagoria they're seeing in their dreams.

ESQ: That’s what we have fiction for.

KR: Totally. I do think fiction is the original dream exchange technology. Thank God for it. It’s different than a movie, because when you write something, you have no idea what another person will do with that spell of language, but you know that they're making it up out of their own materials. I think that’s how it would work, if we could split our dreams from body to body. I hope you have only good ones.

You Might Also Like