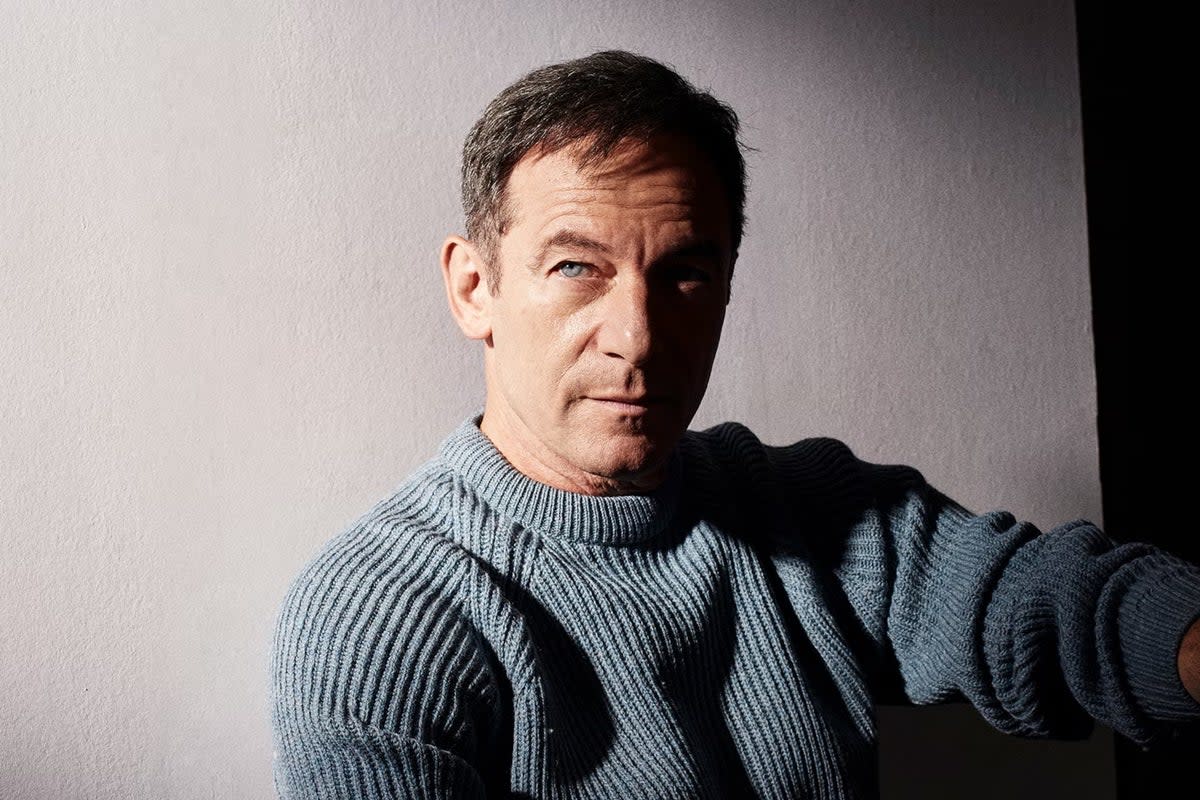

Jason Isaacs: ‘There are people out there who are comfortable in their skin. I don’t know what that feels like’

Jason Isaacs thinks any actor would be a “f***ing idiot to play Cary Grant”. And yet, next week, that’s exactly what we will see him doing, in ITVX’s four-part drama Archie. Written by Jeff Pope, Oscar-nominated for Philomena in 2014, the series dramatises the story of Hollywood’s most prolific leading man, from his traumatic childhood in Bristol to the glories of his movie career, and, in particular, the turbulence of his short-lived marriage to Dyan Cannon, his fourth wife, with whom he had his only child, Jennifer, in 1966.

“Grant was the most beautiful man in every room; men and women wanted him, he was the biggest star in the world for 30 years,” says the 60-year-old Isaacs in between sips of tea and the occasional clang from the adjacent Soho Hotel restaurant kitchen. “I’m a jobbing actor.”

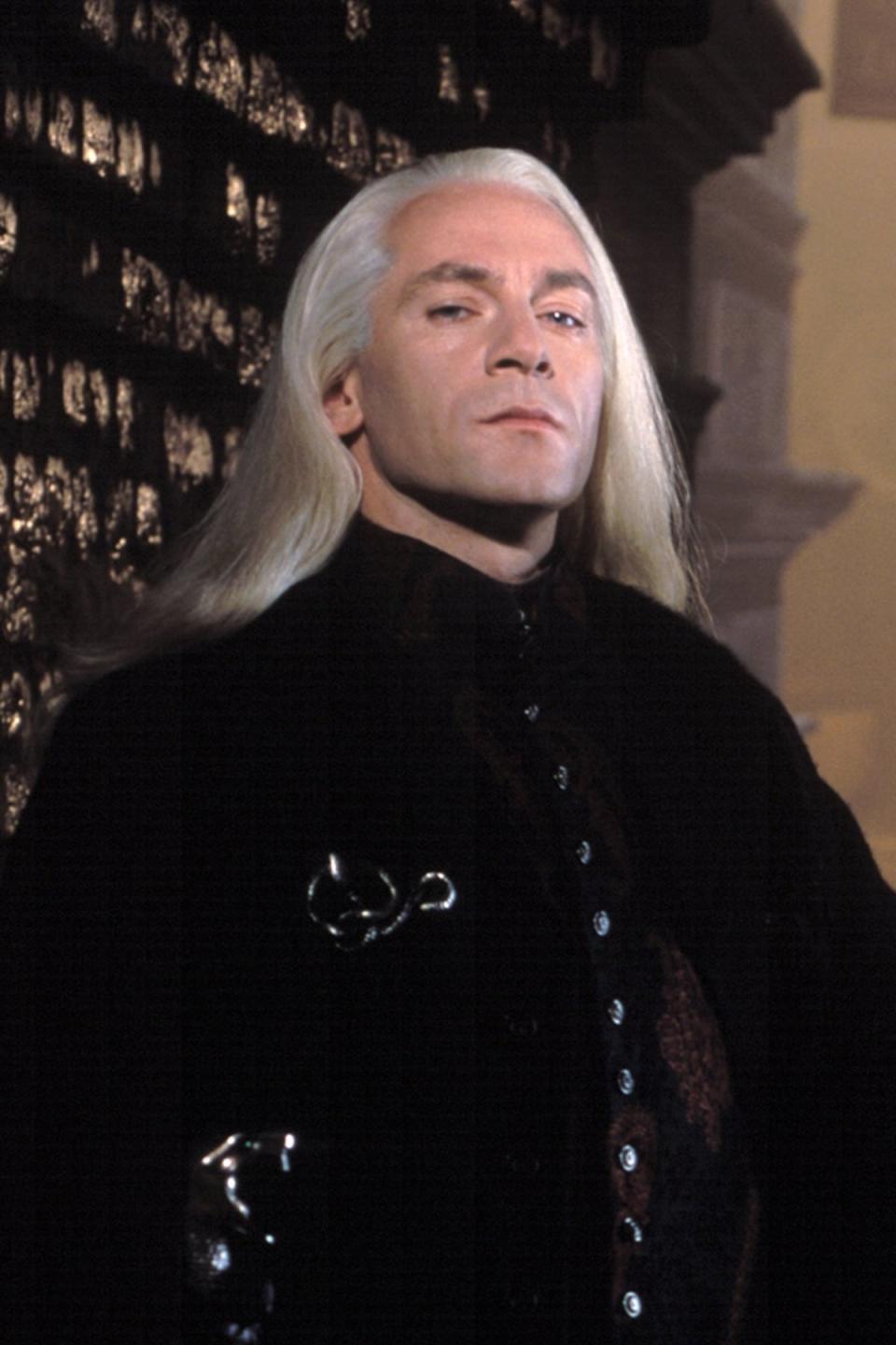

Isaacs is hardly that. In Archie, though, he hasn’t exactly been cast to type. With a career spanning more than three decades, Isaacs is famous for playing not the characters we idolise, but the ones we fear. He’s best known as Lucius Malfoy, the spittingly sinister father of Harry Potter’s arch-nemesis, Draco. He was a fabulously raddled Captain Hook in the 2003 version of Peter Pan. He lent delicious menace to the voice of Count Dracula in Monster Family. He even managed to bring his signature sneer to the third season of Netflix’s Sex Education as Peter Groff – a “pumped-up s*** of a man”, as Groff’s own brother Michael puts it.

“I’ve played some pretty awful people,” Isaacs agrees cheerfully. “But if you asked any of them what they were doing, they’d be able to justify their actions according to their worldview. I don’t take on bad guys that are stroking their invisible moustache at the audience.” In fact, Isaacs has refused villainous roles he has found too two-dimensional. “I’m sure at some point, when I’m older, I’ll regret the money I turned down,” he laughs, careful not to go into specifics.

So what drew him to Cary Grant, the debonair star of An Affair to Remember and To Catch a Thief, who was married five times, frequently took LSD, and died in 1986, leaving behind a legacy as one of the greatest cinema icons of all time? “Cary Grant was a character Archie Leach created,” explains Isaacs, who is uncanny in the role, all tangerine tan and transatlantic tenor. “Archie Leach was so unloved. He was abandoned, physically and emotionally, and had such terrifying experiences as a child that those wounds never healed. But he tried to heal them by getting other people to validate him; to love him, and want him sexually, and admire him as a star. All that seeking other people’s approval just made the wounds inside him bigger and wider.”

Certainly Archie, which is based partly on Jennifer Grant’s 2011 memoir of her father, Good Stuff, is not a drama about the world-famous star everybody knew and wanted to sleep with. Instead it’s a nuanced portrait of the boy from Bristol who grew up in extreme poverty thinking his mother was dead (he would later discover that she was, in fact, still alive) before reinventing himself as a Hollywood heartthrob: a role he would forever try to hide behind. Nor does it sugarcoat the story of a man who tried to control his fourth wife, telling her how to dress, taking away her beloved pet dog following Jennifer’s birth, and encouraging her to take LSD with him – following their divorce in 1968, Cannon sought treatment in a psychiatric hospital.

“It turned not just sour but monstrous,” says Isaacs of Cannon and Grant’s marriage. Isaacs spoke to both Cannon and Jennifer as part of his research, and found Cannon, now 86, more receptive than her daughter. “Dyan is very insightful, whereas Jennifer has the perspective that comes with being Grant’s child. She loved her dad, and it was really useful to find out how devoted a father he was. But she couldn’t have known who the real man was, and what he’d been going through.”

Talking to Isaacs is a lot of fun. It takes some time for our interview to get under way, because he won’t stop asking about me: my job, my CV, my career path. After some convincing, though, he begins to answer my questions, speaking urgently and precisely as if reciting from an invisible teleprompter on which someone has pressed the fast-forward button. Dressed casually in a raincoat and jeans, he is disarming and self-deprecating. He taps me on the arm like an old friend, and enjoys laughing at himself: when I suggest we talk about some of the highlights of his career, he insists we discuss “the lowlights” instead. “There’s so many more of them, obviously,” he giggles, those famously iced-out blue eyes lighting up. But he’s too discreet to name any.

He was born to Jewish parents in a small community in Liverpool before the family moved to London when Isaacs was 11. One of four brothers, he has previously attributed a “streak of cruelty” in his demeanour to having had a “quite combative background” both at home and school. Despite being described as “incredibly cool and aloof” by former school pal Mark Kermode in the critic’s 2010 autobiography, It’s Only a Movie: Reel Life Adventures of a Film Obsessive, Isaacs says he felt like an outsider in his youth. “I never felt like I belonged in any group anywhere,” he says, noting how he had friends “but they were local, and the thing we mostly had in common was that we took a lot of drugs together”.

The Tories are so intellectually, politically and ethically bankrupt by this stage

In 2020, Isaacs marked 22 years of sobriety with a candid Instagram post, thanking “every addict and alcoholic who’s ever lifted [him] up” and explaining how he’d “tried for decades” to get sober before finally admitting he needed help and seeking it out. It’s not a subject he wants to delve into today, but when I mention that we’re speaking just a few weeks after the tragic death of Friends star Matthew Perry, a bittersweet smile spreads across his face. “I met Matt a couple of times,” he says. “I played tennis with him. He was a brilliant tennis player. Oh my God, was he a brilliant tennis player.” He says no more.

Acting didn’t run in the family. Isaacs’ father, Eric, was a jewellery maker, while he once described his mother, Sheila, who died in 2014, as being “of that generation of women who didn’t work, but she could have run a country”. He studied at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, having previously read law at the University of Bristol. “I’d never heard accents like that before except on sketch shows,” he says of some of the more aristocratic students he met at university. Recently, he reunited with some of them at a memorial. “I was with people I hadn’t seen in 40 years and I suddenly heard myself talking in a voice which wasn’t mine,” he recalls, before imitating their RP voices. “I was both aware of it and somehow unable to stop it.”

Perhaps this feeling, of never quite being truly himself, is something Isaacs is only able to shake off in the rehearsal room. “It was the first time I thought this was a place I belonged,” he says of the moment he started acting. “Even though we all had completely different backgrounds, and had nothing that bonded us except for being in this room together, putting on a play, I was addicted to that instant intimacy. Because you’re not having the nonsense conversations most people are having. You’re talking about things that really count, and taking apart the building blocks of human behaviour.”

Grant apparently felt the same. “Like him, I thought, well, I can belong with this group of people because everyone’s looking for connection,” says Isaacs. “Maybe they’ll give me a clue to feel more comfortable. I think there are people out there who are comfortable in their skin, with their friends, and in their relationships. But I don’t know what that feels like.”

Isaacs has previously been vocal on social media, happily tearing down Trump and various Tory MPs, one withering tweet at a time. He has also been outspoken about antisemitism in the Labour Party, and shared his experiences of prejudice as a teenager amid the rise of the National Front, which ultimately led his parents to emigrate to Israel. But today, as the Israel-Hamas war rages into its sixth week and antisemitic hate crimes are up by 1,350 per cent in London alone, he is being circumspect. “It’s just such an enormous thing to talk about that I don’t think it can be tacked onto a publicity interview,” he explains.

Another sensitive topic that Isaacs handles carefully is that of JK Rowling. Nowadays, every Potter alum is asked about her; Daniel Radcliffe, Emma Watson and Rupert Grint have all been critical of the author’s views on gender identity. In 2022, Isaacs told The Daily Telegraph that while the Harry Potter author “has said some very controversial things”, he wouldn’t be “jumping to stab her in the front – or back – without a conversation with her”. Today, he tells me he still hasn’t had that conversation. “I don’t think it’s right to talk to Jo through newspapers and Twitter; I’ve made my views about trans things pretty clear,” he says, alluding to his ardent defence of comedian Jordan Gray, who last year was met with abuse from transphobic Twitter users who called for her to be arrested after she discussed the joys of being trans and stripped off during an episode of Friday Night Live.

He does, however, offer some thoughts on the current political shambles – we’re speaking one day after David Cameron has returned to government, replacing Suella Braverman as foreign secretary. “They’ve had a long time,” says Isaacs of the Conservative Party. “They’ve done nothing right. They’re so intellectually, politically and ethically bankrupt by this stage that they should be swept away as fast as possible.”

In 1966, Grant gave up his Hollywood career, ostensibly to bring up his daughter. “He found that the answer to all the troubles he’d experienced in his life came from not seeking love but giving love,” says Isaacs. “It was only when he started to make someone else the most important person, and become less self-centred, that he began to find any kind of comfort. Being Jennifer’s dad was the best thing that ever happened to him.” It’s something Isaacs can identify with. “One of the things that happens when you have children is you go, ‘Well, I belong here,’” he says. He’s been married to his wife, Emma Hewitt, whom he met at drama school, for 22 years, and they have two daughters: Ruby, 21, and Lily, 18. “They need me to belong here. And that’s a wonderful, liberating, but also overwhelming feeling.”

‘Archie’ is on ITVX on 23 November