Diagnosing ‘warming winter syndrome’ as summerlike heat sweeps into central and eastern US

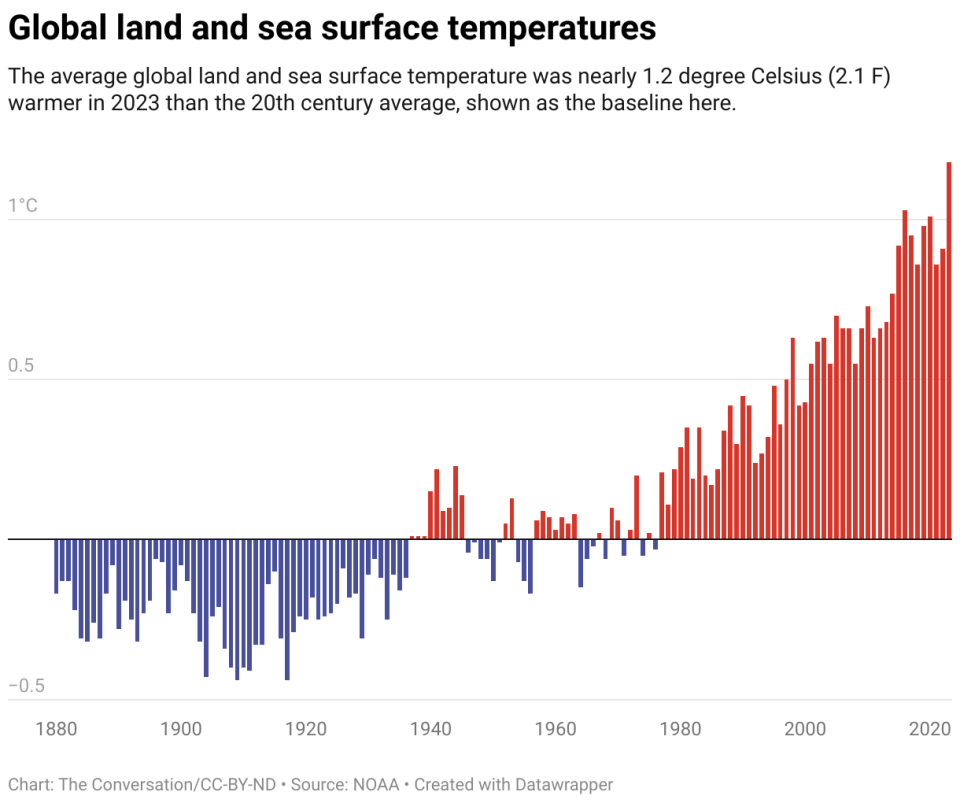

One of the most robust measures of Earth’s changing climate is that winter is warming more quickly than other seasons. The cascade of changes it brings, including ice storms and rain in regions that were once reliably below freezing, are symptoms of what I call “warming winter syndrome.”

Wintertime warming represents the global accumulation of heat. During winter, direct heat from the Sun is weak, but storms and shifts in the jet stream bring warm air up from more southern latitudes into the northern U.S. and Canada. As global temperatures and the oceans warm, that stored heat has an influence on both temperature and precipitation.

The U.S. has been feeling this warming in the winter of 2023-24. Snowfall has been below average in much of the country. On the Great Lakes, the ice cover has been at record lows. Late February saw a wave of summerlike temperatures spread up into the central and eastern U.S., accompanied by dangerous thunderstorms and a fast-growing wildfire in Texas. And forecasters expected another above-average warm spell in early March.

The longer warming trend is evident in changes to growing seasons, reflected in recent updates to plant hardiness zones printed on the back of seed packages. These maps show the northward and, sometimes, westward movement of freezing temperatures in eastern North America.

Ice storms and wet snow

I study the impact of global warming and have documented changes to the climate and weather over the decades.

On average, freezing temperatures are moving northward and, along the Atlantic coast, toward the interior of the continent. For individual storms, the transition to freezing temperatures even in the dead of winter can now be as far north as Lake Superior and southern Canada in places where, 50 years ago, it was reliably below freezing from early December through February.

When temperatures are close to the freezing point, water can be rain, snow or ice. Regions on the colder side, which historically would have been below freezing and snowy, are seeing an increase in ice storms.

The character of snow also changes near the freezing line. When the temperature is well below freezing, the snow is dry and fluffy. Near freezing, snow has big, wet, heavy flakes that turn roads into slush and stick on tree branches and bring down power lines.

Because the climate in which snowstorms are forming is warmer due to global accumulation of heat, and wetter because of more evaporation and warmer air that can hold more moisture, individual snowstorms can also result in more intense snowfalls. However, as temperatures get warmer in the future, the scales will tilt toward rain, and the total amount of snow will decrease.

Indeed, on the warmer side of the freezing line, winter rain is already becoming the dominate type of precipitation, a trend that is expected to continue. With the warmer oceans as a major source of moisture, the already wet eastern U.S. can expect more winter precipitation over the next 30 years. Looking to the future, soggy wet winters are more likely.

Disaster and water planning gets harder

For communities, planning for water supplies and extreme weather gets more complicated in a rapidly changing climate. Planners can’t count on the weather 30 years in the future being the same as weather today. It’s changing too quickly.

In many places, snow will not persist as late into spring. In regions like California and the Rockies that rely on the snowpack for water through the year, those supplies will become less reliable.

Rain falling on snowpack can also speed up melting, trigger flooding and change the flows of creeks and rivers. This shows up in changing runoff patterns in the Great Lakes, and it led to flooding on the East Coast in January 2024.

For road planners, the rate of freeze-thaw cycles that can damage roads will increase during winters in many regions unaccustomed to such quick shifts.

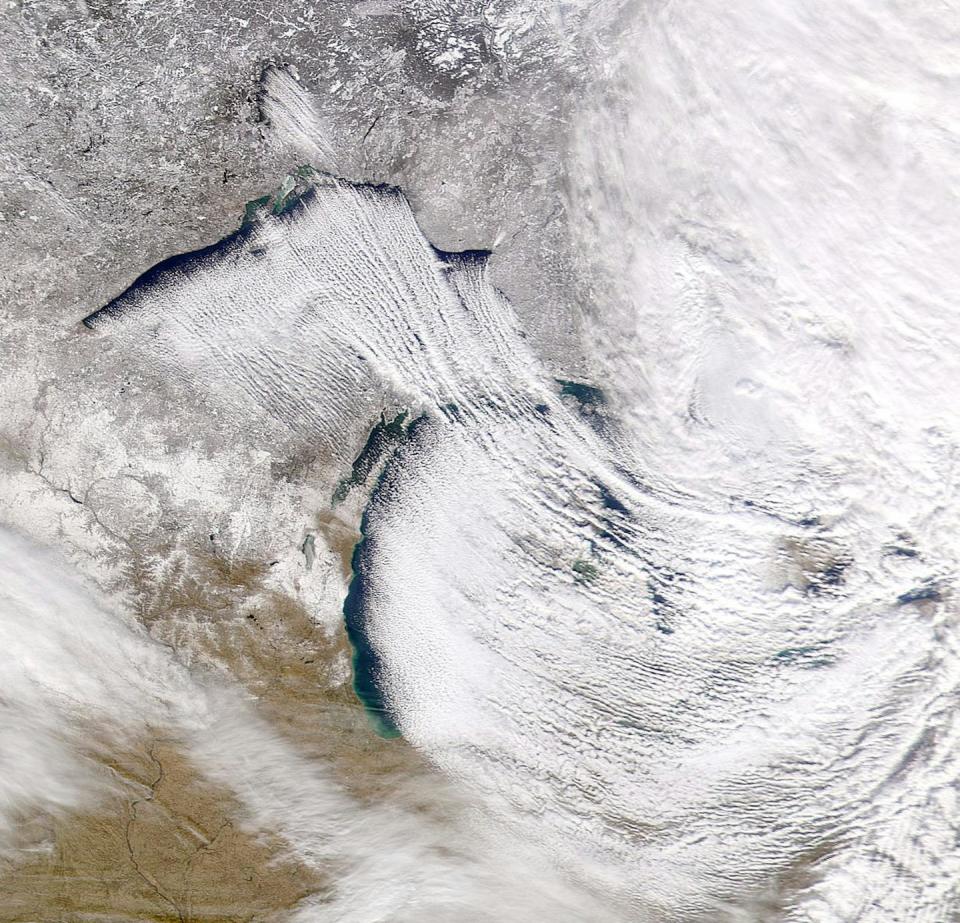

An especially interesting effect happens in the Great Lakes. Already, the Great Lakes do not freeze as early or as completely as in the past. This has large effects on the famous lake-effect precipitation zones.

With the lakes not frozen, more water evaporates into the atmosphere. In places where the wintertime air temperature is still below freezing, lake-effect snow is increasing. The Buffalo, New York, region saw 6 feet of snow from one lake-effect storm in 2022. As the air temperature flirts with the freezing line, these events are more likely to be rain and ice than snow.

These changes don’t mean cold is gone for good. There will be occasions when Arctic air dips down into the U.S. This can cause flash freezing and fog when warm wet air surges back over the frozen surface.

Enormous consequences for economies

What we are experiencing in warming winter syndrome is a consistent and robust set of symptoms on a fevered planet.

Novembers and Decembers will be milder; Februarys and Marches will be more like spring. Wintry weather will become more concentrated around January. There will be unfamiliar variability with snow, ice and rain. Some people may say these changes are great; there is less snow to shovel and heating bills are down.

But on the other side, whole economies are set up for wintertime, many crops rely on cool winter temperatures, and many farmers rely on freezing weather to control pests. Anytime there are changes to temperature and water, the conditions in which plants and animals thrive are altered.

These changes, which affect outdoor sports and recreation, commercial fisheries and agriculture, have enormous consequences not only to the ecosystems but also to our relationship to them. In some instances, traditions will be lost, such as ice fishing. Overall, people just about everywhere will have to adapt.

This article, originally published Jan. 25, 2024, has been updated with above-average heat across much of the central and eastern U.S. in late February and forecast in early March.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Richard B. (Ricky) Rood, University of Michigan

Read more:

Richard B. (Ricky) Rood receives funding from the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).