A huge solar storm is hitting the US: 6 big questions and answers

The biggest solar storm to hit the United States in more than two decades is underway — with impacts to begin Friday evening.

That means Americans as far south as Illinois — or even Alabama — may see the aurora borealis, or northern lights.

Those dancing lights will be the sign of charged particles ejected from storms on the surface of the sun as they collide with the Earth’s magnetic field.

With the Earth increasingly electrified, these storms are potentially disruptive to both radio and the grid — and while this storm is unlikely to cause serious problems, it’s a warning of more serious risks in the future.

“We anticipate that we’re going to get one shock after another, so we’re really buckling down here,” said Brent Gordon, chief of the Space Weather Services branch of the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Here are five things to know about the event — and the vulnerabilities it exposes..

What is happening on the sun?

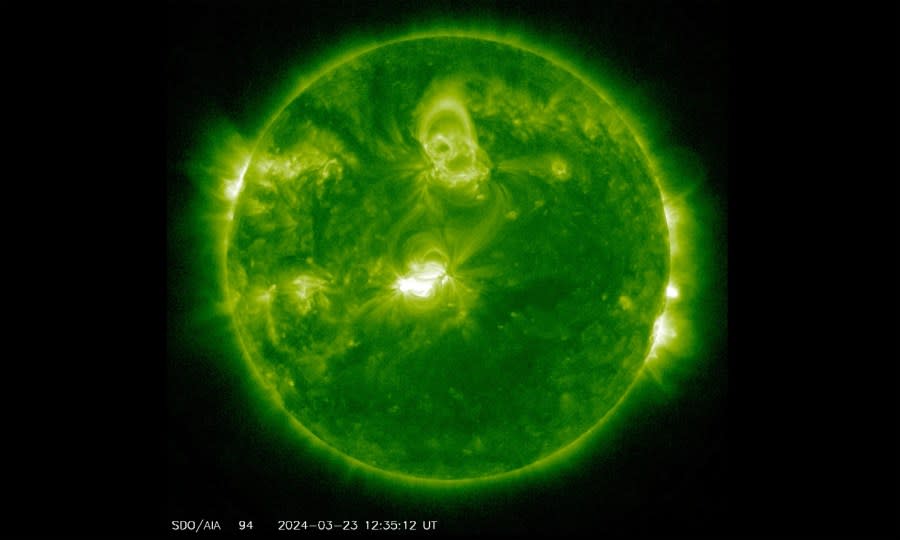

Sometimes the intense magnetic fields from within the sun’s interior push up onto the sun’s surface, forming dark regions, or sunspots. These are enormous regions — many times the size of the Earth — that are thousands of degrees cooler than sun’s usual surface.

Solar plasma can gets stuck in these ‘ropes’ of magnetic flux and flung up into the sun’s atmosphere.

They generally collapse back down into the solar surface.

But sometimes, as these ‘ropes’ snap back into the surface of the sun, they fling charged particles from the sun’s corona out into space. That’s called a coronal mass ejection (CME), and what’s happening tonight and early tomorrow is a series of CMEs heading toward Earth.

Once it reaches the Earth, it will cause a “geomagnetic storm” as the particles hit the Earth’s magnetic field.

How serious is this event?

Experts at NOAA say it’s probably not a big risk to Earth-based systems. But it is a rare and serious event. Like tornadoes and hurricanes, geomagnetic storms are rated on a five-point scale, and this is supposed to be a G4 event.

This is the first such severe storm — and the last “geomagnetic watch” announced by NOAA — since 2005. There have been more recent storms on the low end of the G4 schedule, including a brief, relatively weak event in 2023.

NOAA scientists compared the ongoing “watch” alert to a tornado alert: It means grid managers should go about their business, but be alert. The next level — which the world has yet to hit — would be a warning akin to a tornado warning, which would suggest an ongoing serious event.

But experts emphasized that each “warning” is directed at a specific audience: Tornado warnings go out to everyone in the path of a tornado, but geomagnetic warnings are directed at a much more specialized group.

“For most people on planet Earth, they won’t have to do anything,” said Robert Steenburgh, another space scientist at NOAA. “They’ll be able to go about their daily lives.”

But for “certain sectors of the economy, industry and aviation. There’s some disintegrating effort, because they’ll have to work around the particular storms,” Steenburgh said.

What disruptions can that cause?

On Earth, these impacts are generally minimal, because the Earth’s magnetic field largely shields society from the onslaught of particles. Impacts are relatively restricted to sectors including high-frequency radio or communications from the ground to GPS or airlines — because the particles generate current in the atmosphere that disrupts radio waves.

But the world is increasingly dependent on electricity, which is to say on electromagnetic waves of the sort disrupted by a geomagnetic storm. It’s also increasingly encircled with bands of metal — transmission lines, railroad tracks or even pipelines — that can be turned into electromagnets by the geomagnetic storm.

“Depending on how much [the CME] interacts with the Earth’s magnetic field, the Earth’s field can fluctuate,” sending pulses of electric current down “long conductors like pipelines, railroad tracks and power lines that’s not supposed to be there,” Steenburgh said.

“So our role is to alert the operators of these different systems so that they’re aware and can take action to mitigate these impacts.”

A bigger issue is the world’s reliance on global positioning systems (GPS), which depend on maintaining reliable communication to the network of satellites encircling the globe; GPS was a far less significant part of the economy or navigation system when the last such storm happened in 2005.

Shawn Dahl of the Space Weather Prediction Center said the storm can cause “potential signal loss” between ground and satellites. That means fewer satellites will be able to communicate to the ground at once, making the system’s ability to determine precisely where things are less accurate.

The storm can also “flood” the upper atmosphere with charged particles that persist for days after the storm is over, with real implications for space travel.

Controllers of lower-altitude satellites “are really paying attention now,” Dahl said, because the storm effectively “expands the areas where the satellites are orbiting.” As the atmosphere gets more dense, if controllers aren’t paying attention, their satellites can slow down in the increased friction and begin to drop. “So that’s being accounted for as much as they can.”

One benefit of the reliance on GPS is that the sky is so full of satellites, and the ground so full of receivers, that it helps defray the risk with greater redundancy. “There’s a wide variety of spacecraft providing information, position navigation and timing,” Steenburgh said. “So while the threat is there, it is mitigated.”

How bad can a solar storm get?

The worst geomagnetic storm in recorded history was the 1859 Carrington event, which was named for the astronomer who noticed the unusual spots on the surface of the sun — the effects of which hit the Earth 18 hours later.

That geomagnetic storm — a G5 — caused sparks to fly from doorknobs, blocked telegraph wires and caused auroras to be visible as far south as the Caribbean.

“So completely were the wires under the influence of the Aurora Borealis that it was found utterly impossible to communicate between the telegraph stations, and the line had to be closed,” wrote the telegraph manager of the Rochester Union & Advertiser at the time, according to Ars Technica.

Many effects at the time were spooky. Birds woke up and sang in the bright light of the storm, and telegraph workers across the Eastern Seaboard were able to shut off their batteries and transmit messages using only the induced current of the aurora for power.

The coming storm could reach levels within hailing distance of the Carrington event, Dahl told reporters.

While that was an “extreme level G5,” this storm “could reach a low G5, and we are considering that.” But with the sun 93 million miles away, he said, “it’s extremely difficult to forecast with a very good degree of accuracy the arrival of these events.”

Until the CME gets to about a million miles from earth, scientists “have no way of knowing how impactful these may be,” Dahl said. “Our best guess is G3 to G4.”

A modern Carrington-class storm would be a very big deal, as Kathryn Schulz wrote in The New Yorker.

A National Academy of Sciences Report, Schulz summarized, found that “extensive damage to satellites would compromise everything from communications to national security.”

That, she wrote, was just the beginning. “Extensive damage to the power grid would compromise everything: health care, transportation, agriculture, emergency response, water and sanitation, the financial industry, the continuity of government. The report estimated that recovery from a Carrington-class storm could take up to a decade and cost many trillions of dollars.”

To make things more concerning, the Carrington event was only the benchmark by the happenstance of it being the CME that hit the Earth — more powerful events have blown right by us, including a 2012 storm that missed the earth by nine days.

A NASA article didn’t mince words on the gravity of what had almost happened.

“If an asteroid big enough to knock modern civilization back to the 18th century appeared out of deep space and buzzed the Earth-Moon system, the near-miss would be instant worldwide headline news. Two years ago, Earth experienced a close shave just as perilous,” the agency press team wrote.

“If it had hit, we would still be picking up the pieces,” Daniel Baker of the University of Colorado told the agency.

After writing a 2013 paper on the event for the journal Space Weather, Baker came away chilled.

“I have come away from our recent studies more convinced than ever that Earth and its inhabitants were incredibly fortunate that the 2012 eruption happened when it did,” Baker told NASA. “If the eruption had occurred only one week earlier, Earth would have been in the line of fire.”

What is being done to protect the grid?

In 2016, then-President Obama issued an executive order directing grid operators and infrastructure managers to prepare for “extreme space weather events.”

Space weather, the president wrote, “has the potential to simultaneously affect and disrupt health and safety across entire continents,” and he called on a wide array of government, industry and civil society to get ready.

In her New Yorker piece, Schulz notes that the space industry is largely unregulated, and Bill Murtagh of the Space Weather Prediction Center told her that “I do not think they are ready for a major space-weather event.”

But the grid, he told her, is likely preparing — at least for an event around as strong as the Carrington storm.

At the Friday press event, Steenburgh acknowledged that the addition of renewables to the grid had made it “different than it was in 2005.”

But he said his group had been “working with the power distribution community over the past decade to help them better understand space weather, and their engineers have taken that information and used it to build systems that can protect the power lines more rapidly than before.”

Much of this comes down to triage: identifying what can be taken offline rapidly to protect it in the event of a serious storm, and hardening systems that can’t be allowed to fail.

Where problems arise, he noted, was on massive high-voltage transformer lines. “It’s not on anybody’s [private] line going from the small transformer to their home.”

But Schulz warned that the federal standard for hardening may be preparing for an event weaker than the Carrington event, which is itself weaker than the near-miss of 2012.

And while this storm is unlikely to cause serious problems, and the sun is nearly toward the maximum extent of its 25-year cycle of activity — which will peak in October — solar flare activity often picks up on the back end of the peak.

That could mean years of increased flares, Scott McIntosh of the National Center for Atmospheric Research told LiveScience.

Who will be able to see the aurora?

For this weekend, however, the NOAA team said there was little to worry about — except the question of whether someone who wants to will be able to see the aurora.

“In general, the most visible manifestation of space weather is if you happen to be in an area where it’s cloud free and relatively unpolluted by light — you may get a fairly impressive, aurora display. That’s really the gift from space weather,” Steenburgh said.

Unless the storm is a strong G4, only those in the northern half of the country — meaning north of Northern California — will be able to see it with their naked eye, and then only if they are in areas with little light pollution and clear sides.

A stronger storm may be visible with the naked eye as far south as Alabama.

But there’s a hack, Steenburgh said: use your smart phone.

“If you have a clear night, not many clouds and you put your phone to the sky — you may actually get an image. With some of the recent events, we’ve seen them as far south as Texas, or even down in Central America. So it is possible. Not likely, but it is possible.”

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to The Hill.