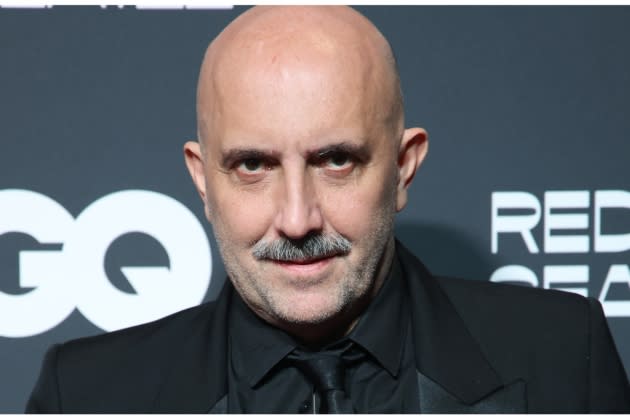

Gaspar Noé Sets His Goals for His Next Film Project After ‘Vortex’

Argentine filmmaker Gaspar Noé is attending the Red Sea Film Festival to give a masterclass. His most recent feature film, “Vortex,” lensed during the lockdown, screened at last year’s edition.

Noé embarked on a far more meditative realistic tone in “Vortex,” compared to his previous films, and explained to Variety that he would now like to make a feature film primarily starring children, and is also thinking about a high-budget feature documentary that can give him full rein to his imagination.

More from Variety

He believes that one of the main challenges facing independent filmmakers is how to navigate the current financing sources, increasingly dominated by streaming platforms.

“I don’t have any platforms at home and don’t watch TV. So when I want to see an HBO TV show like ‘Euphoria’ I have to buy the DVD – that comes out two to three years after the show has been released on the platform.”

He says that many independent directors opt to produce their films themselves to guarantee a cinema release, but then often end up selling to the platforms because of severe financial pressures.

In terms of his next projects, he remarks: “I’ve already done a movie about old age with ‘Vortex’ so the next one is going to be different. I’d like to make a film where the main characters are very young kids, aged between three to five years old, with very little dialogue. I like movies with kids. I don’t have kids myself, but I relate to them.”

He says that he’s also attracted to making an ambitious documentary and has several subjects in mind but prefers not to disclose them at present.

“Vortex” has a quasi-documentary feel, but was made with relatively simple film equipment. This time he’d like to explore an ambitious gamut of filmmaking tools.

“I would love to do a documentary with a big budget, not because of how much money I could spend, but I’d like to make a documentary with all the tools that are used in commercials or feature films, with elaborate special effects, drones and an original soundtrack. Something made for the big screen.”

He says that he has been inspired by some old Russian or Chinese documentaries, that were essentially propaganda films, but could access huge resources, such as marshalling entire army divisions.

“When you see a movie like ‘I Am Cuba’ directed in 1964 by the Russian director Mikhail Kalatozov, the whole island of Cuba was helping him make it. So I could maybe do something that is a mix of narrative and documentary. Or take an example such as the 1929 film, ‘Haxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages.’ It’s a documentary about witchcraft and the inquisition. But you can tell that the guy had a studio, he had extras. I also like that family of documentaries such as ‘Koyaanisqatsi,’ or ‘Powaqqatsi,’ which have really powerful images on the cinemascope screen, without any voiceover.”

Noé says that he is interested to be in Saudi Arabia since it is now beginning to make films, but has seen relatively few Saudi pics up until now, adding that most of the films he gets to see from the region are from countries such as Iran, Morocco, Tunisia or Palestine. “I love Iranian Cinema. I wish I knew more about the rest of the region. I’ve also seen some very powerful Palestinian films.”

Even though countries such as Saudi Arabia have only just kick-started their industry, he believes that there is potential for growth, but this will vitally depend on the creative freedom given to filmmakers. “Some countries are historically more focused on cinema, such as Japan. I don’t know how many world masterpieces they have produced, but they are in the hundreds. It’s not the same when you think about Chinese cinema. No one was talking about Danish cinema until a few years ago and then suddenly, with Lars Von Trier and others, Danish cinema flourished. “

Noé says that after suffering a brain hemorrhage in late 2019 and then with the onset of the pandemic he spent most of the lockdown watching films at home. “I rediscovered a huge part of the Japanese Cinema that I had never focused on. Directors like Mizoguchi, Naruse and Kinoshita. Then I was watching like two movies a day and I discovered how mature those Japanese melodramas between the 1950s and 1970s were. They are incredible.”

The helmer believes that ultimately what makes it possible for a country to produce great films is what’s happening there at a certain moment in time and who is financing films and how much freedom is given. “There are big countries that don’t produce good movies and there are small countries that produce great movies. For example, the Mexican Cinema is doing great now, but it wasn’t always like that.”

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.