France's waning influence in coup-hit Africa appears clear while few remember their former colonizer

DAKAR, Senegal (AP) — When Gabon’s longtime leader was detained in the latest coup in Africa last week, France condemned the takeover but did little to intervene — despite having hundreds of troops in the country. It was a striking break from the past.

African and French observers say that France, under pressure, is finally shedding its postcolonial tradition of “Françafrique” — an unflattering term that smacks of paternalistic influence and quiet deal-making among elites — as its economic and political powers wane and an increasingly self-confident Africa looks elsewhere.

After repeated military interventions in its former colonies in recent decades, the era of France as Africa's “gendarme” may finally be over.

“In the old days of ‘Françafrique,’ this coup would not have happened and, if it did, it would have been quickly reversed,” Peter Pham, a former U.S. envoy for Africa’s Sahel region, said of France’s “muted response” to the coup in Gabon. “Even more than ( the Niger coup in July ), French inaction underscores that the times have changed — Gabon was long the centerpiece of the old cozy postcolonial system.”

In the last three years, a common thread has linked coups in four African countries: All were once French colonies. Some, like Gabon, had continued warm relations. Gabonese President Ali Bongo Ondimba, whose family has ruled the small oil-rich country for more than 50 years, last met with with French President Emmanuel Macron in June in Paris.

But a new strain of anti-France sentiment has emerged elsewhere. Russia’s paramilitary Wagner Group has cozied up to power brokers in places like Central African Republic. China has eclipsed France’s economic influence in Africa. Some former French colonies are joining the Commonwealth, despite no past links to British rule.

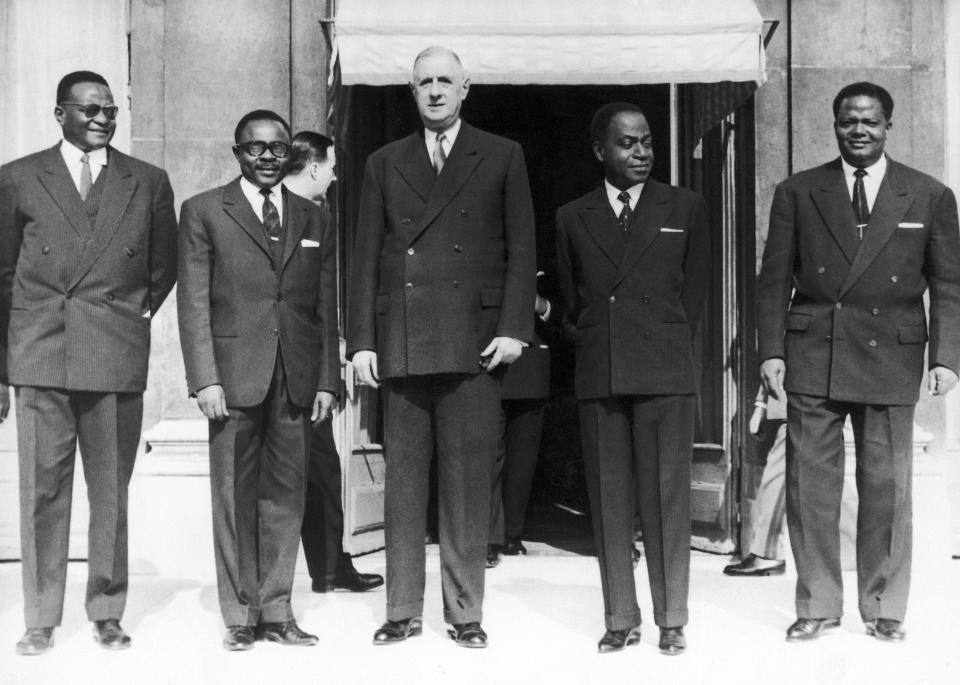

For decades after decolonization, France continued to pull strings and reap benefits in Africa. At times, the heavy-handed influence sparked opposition, but French-backed leaders often returned to power.

Such efforts are now pulling back. Macron last year withdrew French troops from Mali following tensions with the ruling junta after a 2020 coup, and more recently from Burkina Faso, for similar reasons. Both African countries had asked for the French forces to leave.

France also suspended military operations with Central African Republic, accusing its government of failing to stop a “massive” anti-French disinformation campaign.

Macron, in a speech last week to French diplomats, decried “an epidemic of putsches” in the Sahel region.

Macron’s predecessors, including François Hollande, Nicolas Sarkozy, Jacques Chirac and François Mitterrand, had all launched new French military operations on the African continent. Macron did not.

Macron, the first French president born after the end of colonial era, has made it clear that France has turned the page of postcolonial interventionism. But even though the word “partnership” has been Macron's rallying cry in Africa, some ill feeling lingers.

“France stirs up conflict in Central African Republic and is putting pressure on authorities to not bring forth real development policies,” said Anicet L’appel, publisher of the local Adrenaline Info, seen as close to the government that has been gravitating toward Russian interests in recent years.

In Gabon, the Bongo family has had deep and enduring ties to France for generations. Writer and analyst Thomas Borrel called it “emblematic” of Françafrique — a local dynasty marked by corruption, French business ties and a vague guise of democratic practices.

The late Jacques Foccart, a shadowy French high-ranking bureaucrat known as “Monsieur Afrique” for his efforts to keep former French colonies close, recalled in his memoirs how in the mid-1980s, the younger Bongo quietly floated in Paris the idea to set up constitutional monarchy in Gabon. The French laughed it off.

Macron has said nothing publicly about Gabon since the coup.

Several longtime leaders of former French colonies are still standing and have a collective 122 years in office: Cameroon’s Paul Biya with 41, Republic of Congo’s Denis Sassou Nguesso with 39; Djibouti’s Ismail Omar Guelleh with 24; and Togo’s Faure Gnassingbe with 18.

Seidik Abba, a Nigerien researcher, said it’s been slightly lost on France that Africa has changed and Paris isn't the only global power available.

“The former colonies are looking (out) for their interests. They’re not looking at their history with France,” said Abba, who is president of the International Center for Reflection for Studies on the Sahel, a Paris-based think tank. “The diplomats and other officials continue to consider that they have exclusive relations with African countries.”

But many French connections remain, even in coup-affected countries.

“It’s tempting to talk about an end to Françafrique,” said Borrel, a spokesperson for Survie, an advocacy group that denounces France’s postcolonial policies in Africa. “Françafrique is characterized by institutions still in place — French troops still in Africa; the CFA franc currency; and a French paternalistic culture that must be changed, including at the summit of the French state.”

Today, France retains more than 5,500 troops across six African countries, including more than 3,000 in permanent bases in Gabon, Djibouti, Senegal and Ivory Coast, plus about 2,500 involved in its military operation in Chad and Niger.

France has maintained its troops in Niger even though mutinous soldiers ousted President Mohamed Bazoum more than a month ago. On Thursday, the junta revoked the diplomatic immunity of the French ambassador, who has ignored their order that he leave.

In neighboring Mali, many soured on the French troop presence after it failed to rid their country of Islamic extremist fighters. Pro-Russia groups on social media fomented the disgruntlement.

“Their departure from Mali is a good thing, because our soldiers and their Russian allies are going to effectively fight the terrorists,” said Timbuktu resident Harber Cissé, alluding to what European officials say is the presence of Wagner Group fighters in Mali.

The changing sentiments also reflect a simple fact: Today, the vast majority of Africans are too young to have lived under French rule. Much of Francophone Africa won independence in 1960. The last French colony, Djibouti, became independent in 1977.

Guelleh, the Djibouti president, appeared to finally sense a growing threat of coups in Francophone countries after the events in Gabon, denouncing it in the strongest terms. In Rwanda, longtime President Paul Kagame “accepted the resignation” of a dozen generals in an abrupt security shake-up. Cameroon’s even more veteran president, Biya, did likewise the same day.

Perhaps the most significant drift in Africa is a cultural one. France simply doesn't serve up the aspirations it once did.

France “was the land of prestige,” Djibouti-born poet Chehem Watta, 60, told Le Monde this year as part of a project exploring the changing France-Africa relationship. But over the years, shrinking French funding and military presence, along with tightening visa restrictions, “tarnished” France’s image, he said.

In Abidjan, university student Laurent Wassa of Félix Houphouët-Boigny University — named for a French lawmaker who became Ivory Coast's first postcolonial president — said he stopped wanting to study in France, because he thinks the quality of education he would receive has gone down based on what he’s heard.

“Studying in France isn’t as much of a dream as it used to be,” he said. He'd prefer a scholarship in China.

Antoine Glaser, a journalist whose 2021 book translates as “Macron's African trap,” said that Africans are dictating the changing relationship.

“It's not a French president who's going to decree the end of Françafrique, that's useless,” he said. “It’s Africa that’s going to straighten up France when it comes to paternalism, and getting a new perspective.”

___

Keaten reported from Geneva and Cara Anna from Nairobi, Kenya. Associated Press writers Jean Fernand Koena in Bangui, Central African Republic, Baba Ahmed in Bamako, Mali, Toussaint N’Gotta in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, and Sylvie Corbet and Oleg Cetinic in Paris contributed to this report.