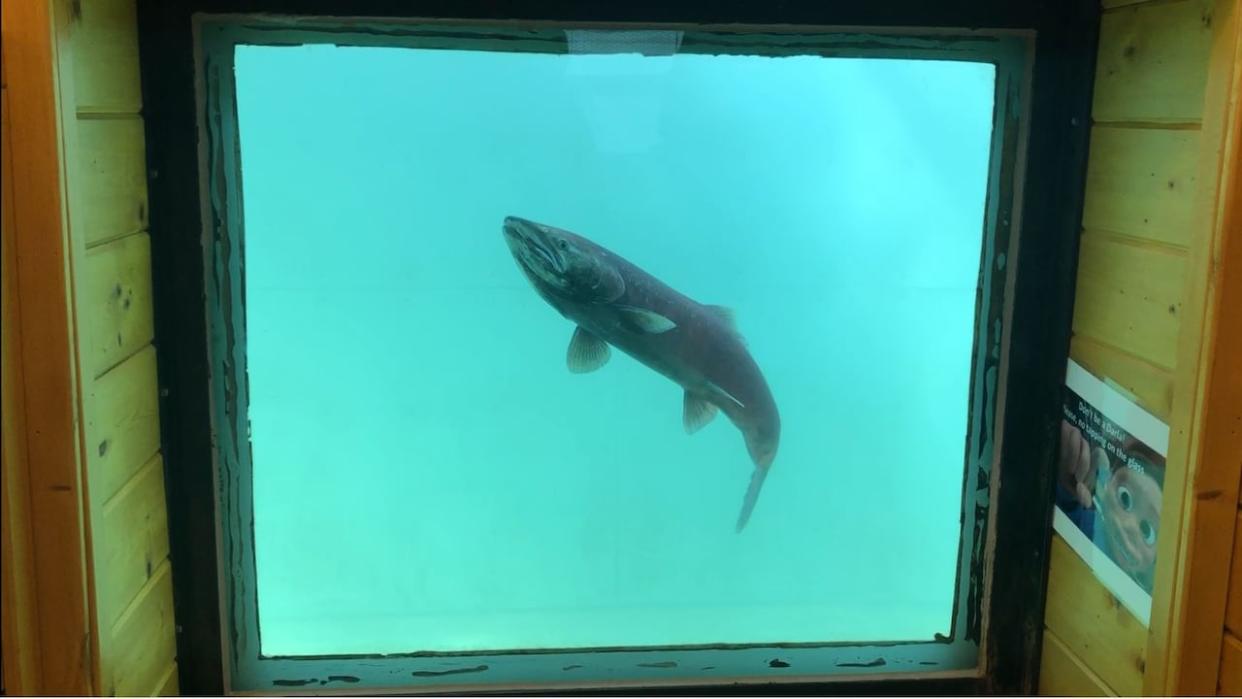

Environmental factors likely hurting Yukon River chinook salmon population, study says

Environmental conditions likely have a significant impact on Yukon River chinook salmon and that's something that fisheries managers need to pay attention to, according to a new scientific paper.

The paper, published in the most recent edition of the Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, saw researchers pull up decades' worth of data on "environmental and ecosystem variables" like water temperature, precipitation and the date of ice break-up on the Yukon River at Dawson City. They then looked at the possible effects of those variables on chinook at various stages of life, from eggs to mature fish migrating back to their spawning grounds.

The impacts "weren't trivial," lead author Alyssa Murdoch told CBC News in an interview.

"We were finding it on the scale of, you know, losses of about tens of thousands of fish," she said.

In particular, researchers found that wetter conditions in the Yukon River watershed could have a devastating effect on juvenile chinook — less than three centimetres of additional rain could result in an average loss of more than 13,000 salmon.

That's because more rain means higher waterflow, which could displace the young fish and disrupt their feeding.

Murdoch also pointed to the finding that a water temperature increase of just 1.2 C on the Yukon River during the chinook spawning migration can result in a run size being reduced by, on average, 12,000 fish.

"Twelve thousand salmon really is quite huge in extremely low returns where every fish counts," she said.

Chinook on the Yukon River, in recent years, have seen sharp declines in their run sizes, with 2022 and 2023 being the worst and second-worst runs on record, respectively. According to preliminary numbers for 2023, only 58,529 chinook entered the mouth of the river in Alaska, with an estimated 14,752 of them making it into Canada — only about a third of the number needed to meet the lower end of the spawning escapement goal.

Other environmental factors that researchers found were likely to have a negative impact on chinook were increased precipitation during spawning and egg incubation, warmer and longer springs and summers, and an increase in the number of pink salmon in the ocean.

A later break-up date of ice on the Yukon River at Dawson City also could have a negative impact, with researchers theorizing that the longer the ice is in place, the longer smolts are delayed in getting to coastal areas and the ocean.

The findings related to temperature and precipitation are particularly relevant, the paper noted, since Yukon watersheds are expected to get warmer and wetter as the climate changes.

Warmer water can be positive in some cases, researchers find

Murdoch, though, said that researchers also found that chinook are "very complicated," and that in some cases, environmental changes may actually have a positive effect.

Warmer water during spawning itself as well as over the winter, for example, may actually improve survival for chinook eggs. Similarly, an increase to sea-surface temperatures of less than a degree in the winter may also improve survival for chinook in the ocean-stage of life, and snowier winters had a positive correlation with salmon numbers.

However, the positives aren't enough to outweigh the negatives.

"I think that the returns kind of speak for themselves," Murdoch said.

The paper calls on fisheries managers to seriously consider the impacts of climate change when making decisions, for more collaboration across borders, and in particular, for managers to consider increasing escapement goals to account for environmental effects.

"Salmon are facing these warmer and more unpredictable environments each year and of course that means that they might not be able to produce like they used to," Murdoch said. "And the management goals that were developed based on these older conditions, they might not be as effective moving forward."

One salmon expert, though, said he wished researchers had taken their analysis a step further.

Sebastian Jones is a fish, wildlife and habitat analyst with the Yukon Conservation Society and he wasn't involved in the research paper. He said he was surprised researchers didn't look at how historic overfishing, both in the ocean and on the river, weakened the chinook population and made it more susceptible to negative environmental impacts.

"It would be really great to see a similar paper that casts its net, so to speak, just a little bit wider," he said.

However, he said he supported the call for higher escapement goals, and thought the paper would still be useful in upcoming management meetings.

Murdoch agreed that the paper shouldn't be looked at in isolation, and said that its findings are meant to complement other research underway.

"There's definitely stuff at play that we don't touch on in our study and that could be included in future iterations of this work or in other work," she said.

"Really, our main message from this is that we really need to consider the big picture of all of the possible threats that salmon may be facing when making these management decisions."