This Year Marks the 75th Anniversary Since Former Scientists Created the Doomsday Clock

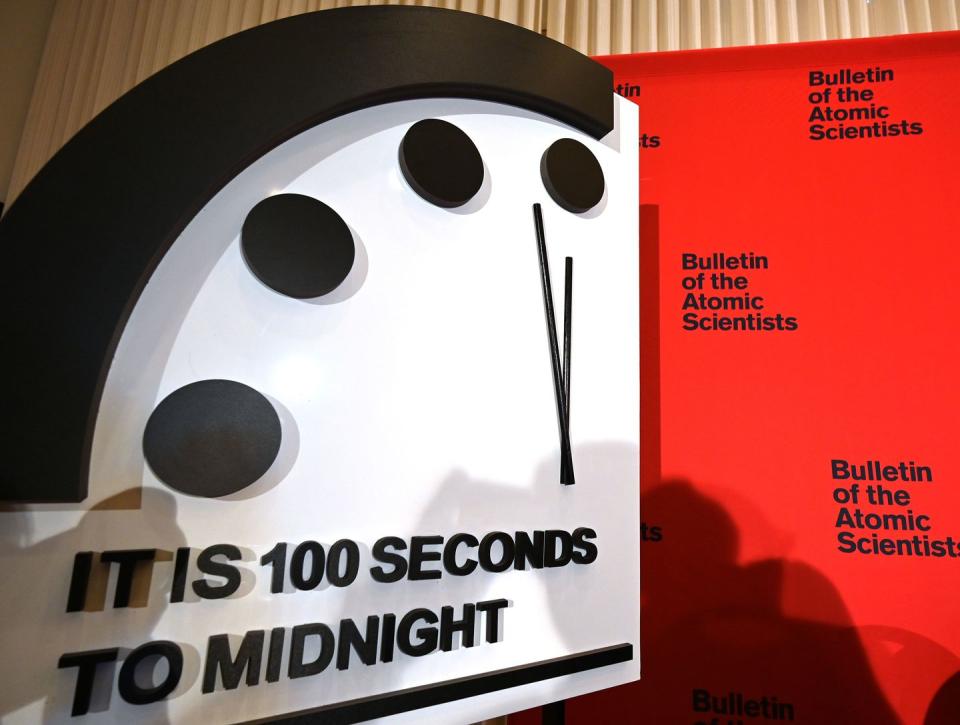

For the third year in a row, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has decided to keep its Doomsday Clock at 100 seconds to midnight.

The Doomsday Clock isn't updated on a set time frame, but rather, as events dictate. You can thank the pandemic, climate change, the rise of misinformation, and the threat of nuclear war for this update.

This year marks the 75th anniversary since former Manhattan Project scientists created the Doomsday Clock in 1947.

Life as we know it is still on the brink of disaster.

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, a nonprofit organization made up of scientists and global security experts, has published a new statement deriding the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic and expressing concern about nuclear weapons, misinformation, and climate change.

☢️ You like nuclear. So do we. Let's nerd out over it together.

The organization announced for the third year in a row that it is keeping its figurative Doomsday Clock at 100 seconds to midnight—the closest we've come to a symbolic apocalypse since the first tests of the hydrogen bomb in 1953. This year also marks 75 years since the organization began tracking our inevitable demise.

"Steady is not good news," Sharon Squassoni, a research professor at George Washington University's Institute for International Science and Technology Policy and a co-chair on the Bulletin's Science and Security Board, said during a press briefing on Thursday. "In fact, it reflects the judgment of the board that we are stuck in a perilous moment, one that brings neither stability nor security."

The experts cited a lack of progress and coordination in the fight against climate change, the ongoing pandemic and evolution of troubling new variants, and North Korea's continued efforts to develop nuclear weapons. They also blamed use of technology in misinformation and disinformation campaigns; the development of hypersonic weapons by the United States, Russia, and China; recent space junk-generating ASAT tests; and deteriorating talks between the world's superpowers.

Still, the 2022 statement from the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists did offer up a few positive developments, citing a return to the Paris Climate Accord and the Iran Nuclear Deal, and the extension of New START arms control agreement. "A more moderate and predictable approach to leadership and the control of one of the two largest nuclear arsenals of the world marked a welcome change from the previous four years," they wrote.

But it was not enough to move the dial backward. While the reason for the Doomsday Clock's slow march toward societal ruin is, frankly, pretty obvious, there's another question you may have. What is this metaphorical clock all about, anyway?

Enter the Atomic Era

The year was 1945, and the atomic bomb had just changed the boundaries of science forever. Like the advent of the machine gun, tank and airplane, the atomic bomb changed the shape of warfare. Unlike previous weapons, however, the bomb threatened to destroy the whole human race.

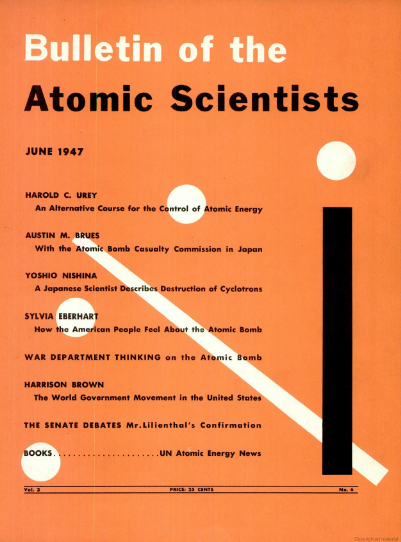

There was no concrete way to measure or or explain the atomic bomb in comparison to more traditional arms, so a group of scientists—among them, Albert Einstein, Hy Goldsmith and Manhattan Project alums J. Robert Oppenheimer and Eugene Rabinowitch—determined the public needed a nontechnical magazine to become fully aware of such dangers. Enter the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. "To say the Bulletin was founded on a shoestring would be to describe it as overdressed at birth," declared a 1949 issue of the magazine.

The transition from government scientists working with a wartime budget to struggling magazine editors was not an easy one. The magazine started as a six-page black-and-white newsletter, and by 1947, its publishers had come up with enough funds—by taking on debt and taking donations—to print a full issue.

To actually put the magazine out, Goldsmith turned to Martyl Langsdorf, the wife of fellow Manhattan Project veteran Alexander Langsdorf. Speaking to the History Channel for an episode of Modern Marvels, Langsdorf recalled that "he gave no instructions, except that it can't cost much ... All the scientists felt an urgency to explain what had happened with the bomb, and because of the extreme urgency, I remember, a clock seemed to be important."

"The hands of the clock of doom have moved again," wrote Rabinowitch in 1953. "Only a few more swings of the pendulum, and, from Moscow to Chicago, atomic explosions will strike midnight for Western civilization." Rabinowitch's writing has a style of tension and doom fitting the atomic era, and the name stuck.

The Doomsday Clock isn't updated on a set time frame, but rather, as events dictate. In fact, the most recent move is only the 23rd in the clock's 70-year history. When Rabinowitch wrote those fateful words in 1953, he placed the clock at 2 minutes to midnight, the closest it had ever been.

The Doomsday Clock went backwards when the SALT and ABM treaties were signed in 1972, and then forward again in 1998, when both India and Pakistan tested nuclear weapons. The clock moved as far back as 17 minutes in 1991 with the collapse of the Soviet Union, almost enough time to squeeze a TV show before the end of the world.

This focus on nuclear came about because, current publisher Rachel Bronson notes, in "1947 there was one technology with the potential to destroy the planet, and that was nuclear power." The ways humanity has invented to destroy itself have multiplied since then, and in 2007, the Doomsday Clock began to consider climate change as "a dire challenge to humanity."

The Doomsday Clock is one of the rarest things available to scientists: an easily recognizable icon that can grab a passerby with no scientific background. In short, it's exactly what Rabinowitch and Goldsmith wanted.

You Might Also Like