How are emperor penguins surviving on melting ice caps? Bird poop brings us one step closer to finding out

Scientists found four previously unknown emperor penguin colonies in Antarctica, a discovery that increases the known population of the iconic species but also uncovers the impact of melting ice.

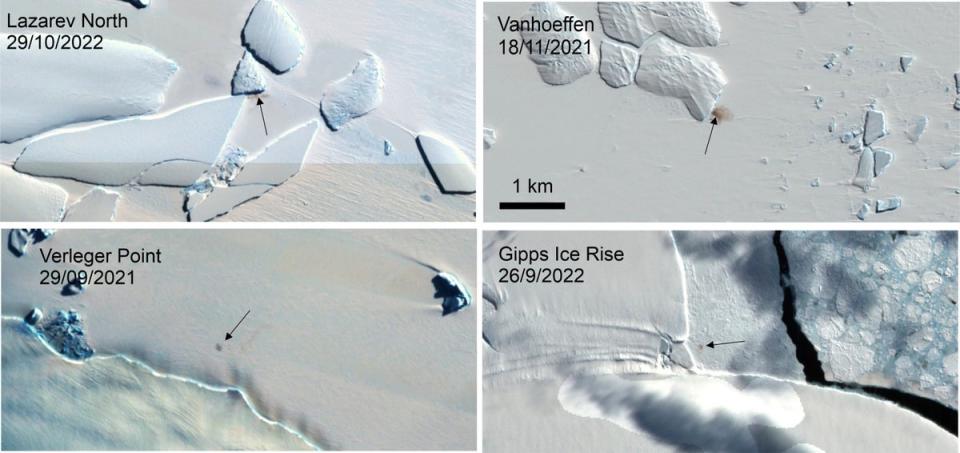

Satellite photos from the Brunt ice shelf revealed four new colonies of emperor penguins. The discovery was made by satellite images which captured “guano”, otherwise known as bird poop, on the ice, a scientist from the British Antarctic Survey told NBC.

This discovery takes the total number of nesting grounds known to scientists to 66.

The largest of all penguins, the species is nearly threatened and predicted to go extinct by the end of the century.

While the discovery of these colonies is welcome news and adds a few thousand more penguins to the estimated population of 550,000 remaining, scientists say it also shows how penguin colonies are forced to move their colonies as existential threats mount.

“Emperor penguins have taken it upon themselves to try to find more stable sea ice,” Peter Fretwell, a researcher at the British Antarctic Survey, which discovered these colonies, said.

During winter, colonies of thousands of emperor penguins live and breed on the frozen sea ice clinging to the Antarctic coast. But over the years, the ice beneath their feet has been melting and breaking off, leading to thousands of penguins dying after drowning or freezing to death.

Last year, at least 19 penguin colonies had total breeding failures due to ice melt, causing a mass die-off of chicks.

The constant threat of losing their habitat has now forced them to relocate to more stable breeding grounds. Researchers regularly monitor where they move using satellite photos.

The new pictures, shared by the British Antarctic Survey, show the hordes of penguins moving against the bright white snow, standing out as brown splotches on the landscape.

Three of the colonies researchers spotted on the Brunt ice shelf were small – fewer than 100 birds. But the fourth group, a colony that scientists thought had vanished, had more than 5000 birds.

One penguin colony near Halley Bay appears to have moved around 30 kilometres (19 miles) to the east, Mr Fretwell said .

“The losses we are seeing through climate change probably outweigh any population gain we get by finding new colonies,” he adds.

He said unstable conditions beginning in 2016 had made the old location dangerous for emperor penguins.

As continued burning of fossil fuels heats up the planet and more and more ice melts in the Antarctic, more “penguins will be on the move,” Mr Fretwell said.