Richard Linklater: ‘Would Dazed and Confused be made today? No way’

You’re only alive because I’ve chosen not to have you killed. Just remember that,” Richard Linklater tells me, with a suspiciously evil grin. We’re in Soho talking about Hit Man, the new Netflix film from the 63-year-old director of Boyhood and the Before trilogy. Linklater, today all in black, his hair long and greying, is fascinated by our obsession with hired killers, and the way they spill over from the big screen and the pages of crime fiction into real life. “It’s where pop culture myths meet reality,” he says. “I had a lot of knowledge and interest in that world, because it was so bizarre. To me, I guess, it was always a comment on consumer culture. That you could just purchase the death of someone else so easily, like your groceries or something. But it’s very common.”

In the real world, he says, “there’s this cold-blooded killer out there who, for money, will kill your ass. My darkest impulse after all these years is that people are empowered by the notion that they can hire someone to kill someone, if things got bad. You know what I mean? It’s a last resort.”

It’s a pitch-black thought. Hit Man, on the other hand, is a blast of pure dopamine, a tautly plotted crime caper that sizzles and pops in the sweaty streets of New Orleans. Loosely based on a 2001 true-crime article in Texas Monthly, it stars Glen Powell as Gary Johnson, a nebbishy college professor who has a side hustle with the local police department, setting up stings by posing as different hit men. On the surface, it may seem like a departure for a director as esoteric and experimental as Linklater. After all, this is a man who first came to attention in 1990 for the quiet, Generation X existentialism of Slacker, before leaving an indelible mark with his ambling paean to Seventies high school in Dazed and Confused (1993); alienation, meanwhile, pervades his 2001 animation Waking Life. But slowly, fastidiously, Hit Man reveals unforeseen depths: by finding profundity in the everyday, it unites much of what we’ve come to expect from Linklater’s output. As with his biggest mainstream hit to date, the riot that is School of Rock (2003), it’s also very funny.

“I think, at heart, I like to make comedies, which are kind of mainstream by definition,” he says. “Even the darkest indies I think are funny.” He decides he may be “a little more of a showman” than other indie directors, but he’s at pains to point out “that maybe they didn’t get those opportunities”. Besides, Linklater says, he doesn’t differentiate between his most crowd-pleasing work and his most obscure. “Every film I make, I think, ‘Oh, everybody’s going to love this.’ I mean, I love it; why wouldn’t they? Then you learn time and time again, ‘No, not everybody loves it. Even your own distributor doesn’t love it.’ So that’s the cruel fate of cinema. But, you know, I haven’t really done that many studio films.”

Certainly, Hit Man has the feel of a big studio film. Easily Linklater’s best work in a decade, it’s confident and stylish, with noirish shades of Double Indemnity and a classic Hollywood leading-man performance from a never-better Powell, who also co-wrote the screenplay. It’s a genuine crowd-pleaser that never misses its target. Shown to audiences at London Film Festival last October, it was rapturously received, its widly entertaining denouement met with whoops and cheers. It’s a shame the film’s only getting a very limited theatrical release, I say. Only last month, Powell was suggesting that his previous film, Anyone But You, wouldn’t have had “any cultural impact” if it had been made for a streamer. What does Linklater make of that?

That’s a question for the movie studios, he says, becoming exercised. “You should call every studio, [and ask them] ‘Have you watched this movie?’” Every one of them said, “Yeah, not for us,” he tells me. “You can’t blame me – we did this film for nothing, you know. Glen and I wrote this on our own; no one hired us. The industry didn’t want to make this film.”

If Linklater sounds defensive, he doesn’t mean to, he says. In person, much like his films, he is laidback and voluble, the cadence in his Texas drawl often rising at the end of a sentence, as if followed by a question mark. But ask him about the state of the movie industry and you sense a growing disillusionment. “My attitude towards the studios is ‘What do you want?’” he says, shrugging his shoulders. “You heard the audience response [to Hit Man], but the truth is the studios didn’t. Their assistants heard it. They hear a quote or something.

“It says something about our times, and the lack of confidence studios have in adult-audience movies, for them to not even show up at a movie that’s not a franchise or pre-existing something,” he continues. “I mean, we’re getting toward original territory; this is scary to them. You’re less likely to lose your job as an executive greenlighting the fourth sequel to something than by taking a risk on something you think audiences might like.”

Linklater calls it an “infantilisation culture”. The studios, he suggests, are cynically targeting the widest possible audience by aiming films at “a 12-year-old’s mentality”. Growing up in Houston in the Seventies, the young Linklater would watch sophisticated films such as the neo-noir Klute, starring Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland. “The adult world would look a little scary,” Linklater says, “but pretty enticing. Maybe it was the sex. Maybe it was aspirational.”

You’re less likely to lose your job as an executive greenlighting the fourth sequel to something than by taking a risk on something you think audiences might like

Maybe that’s why Linklater went about making a film as sexy as Hit Man, which has an alchemy that owes much to the off-the-scale chemistry between Powell and Adria Arjona. In a recent interview, Linklater said: “Sex and violence is what cinema is great at. Sex was always the great seller; I don’t know why they backed off from that.” Why does he think they did? Has it anything to do with studies suggesting that Gen Z viewers want less sex on screen? “Maybe they saw a lot of bad sex,” he says, taking a deep breath. “Stupid, gratuitous sex. Maybe they just don’t trust it any more, especially if it looks nothing like their own life or something that looks enticing. I don’t know. I can’t believe humans would not be interested in sex that they found interesting.”

If sex is out on screen, so perhaps are affectionate portraits of raising male children, like the one Linklater created in his Oscar-winning, passage-of-time opus Boyhood (2014). As Ruth Whippman, the author of BoyMom: Reimagining Boyhood in the Age of Impossible Masculinity, wrote recently in The New York Times, boys now grow up “in the shadow of a wider cultural reckoning around toxic masculinity”. And the job description for a mother of sons, Whippman has suggested, seems to be “shrinking to a single pinprick measure of success, to raise a boy who won’t rape anyone”.

“There’s been this reduction of the male, you know,” Linklater says. “The patriarchy has been notoriously toxic and harmful in some broad way. But it shouldn’t reflect on every individual mother or brother.” When Linklater was a teenager, he says, “it’s like you’re trying on masculinity. It’s a tough thing, because it’s kind of extreme; there’s violence there. It’s like, oh, we’re doing this because this is how boys act? Is this how I act around girls? Is this me? I don’t know. There’s a lot of conflicting messages and a lot of negative impulses coming from all directions. Everyone’s bumbling through growing up, you know.”

He seems to be suggesting that we “give guys a break”. “I give everybody a break, especially young people,” he says. “I’m really slow to attach evil to young behaviour before the age of, let’s say, 25. I was a little lucky I had older sisters and a single mom. So I kind of had a leg up on my competition. But I knew guys who just didn’t understand women. So give them a break, and vice versa... every sexuality in between, everyone’s just trying to figure it out.”

How hard would it be to get Boyhood – which Linklater shot over 12 years – greenlit today? “Someone could get it made,” he says. “You’ve just got to have the idea, you’ve got to work for nothing. I think if you can keep your budget low, there are a lot of directors of all stripes who could get something like that [made for] a $200,000-a-year investment.”

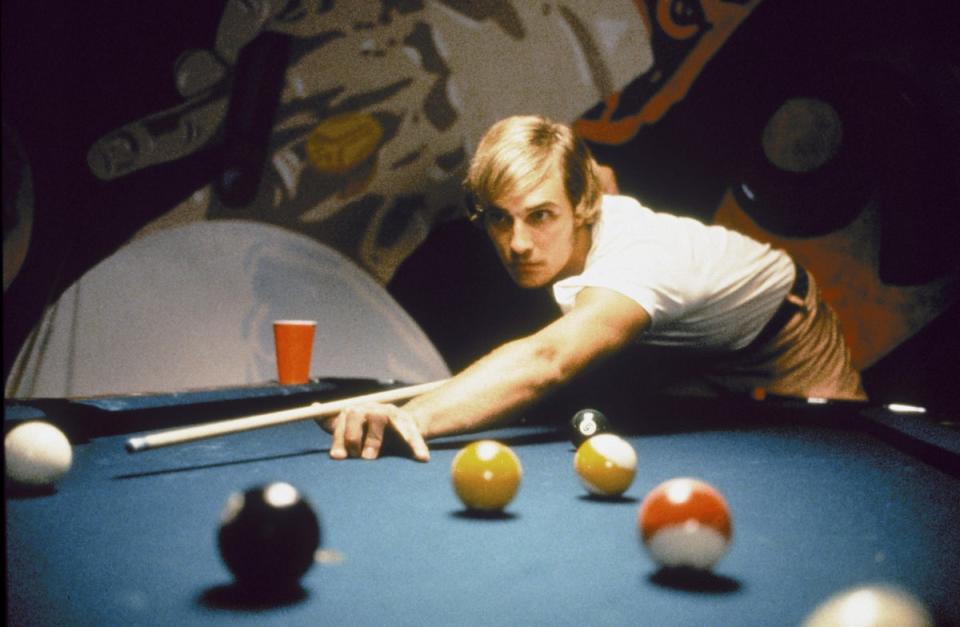

Dazed and Confused, on the other hand... “No way,” says Linklater. Set in 1976, the film follows a group of teenagers running wild on the last day of term to the strains of Aerosmith, ZZ Top and Black Sabbath. “They’re just not making $6m indie-ish type movies any more,” he explains. “That’s not part of their slate. Back then they would have been like, ‘Oh, we’ve got a couple of big films, and there’s this script we like from this kid who did that other indie film – let’s give him a chance.’ You know, they don’t think like that any more. They can’t afford to.”

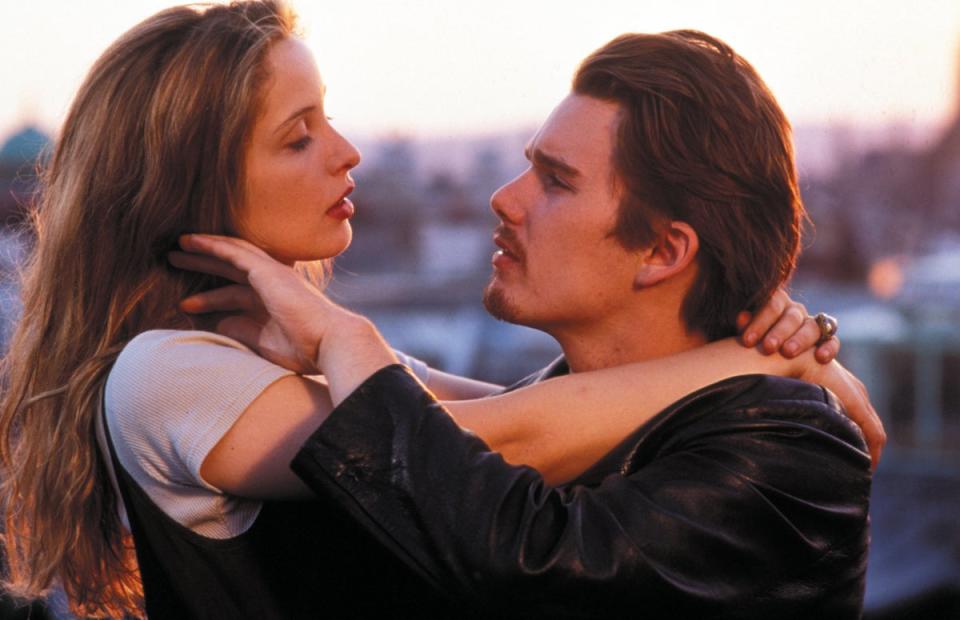

Linklater is hopeful of adding to the triptych of Before Sunrise (1995), Before Sunset (2004) and Before Midnight (2013), starring Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke. Each takes place over a 24-hour period and follows another chapter in the romantic relationship of Celine and Jesse, who, in the first film, meet on a train, get off at Vienna, and spend a day and night together. “We obviously missed our nine-year interval, but that was pretty f***ing arbitrary to begin with,” says Linklater. “We never set out to do that. There hasn’t been an attempt to make another one, or a rejection. But I think we will come together when we have something to say, some new stage of life.”

Meanwhile, Linklater is working on an adaptation of Merrily We Roll Along, the Stephen Sondheim musical, with Paul Mescal in the role of a composer. Where Boyhood covered 12 years, Merrily will be shot across 20, taking Linklater into his eighties. Back when he was coming of age, an injury put paid to his college baseball career and led to him working on an oil rig, before he made his 1988 film debut, the existential tone-poem of a movie It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books. Could that young man have anticipated the director he’s become?

“I probably wouldn’t have thought I would make films that are that funny,” he says. “I was kind of quiet. And I was really obsessed with cinema. But maybe I didn’t know I would have a knack for entertaining. I mean, a lot of people would argue I’m not... you know, I’m a weirdo and all that. But I think I’m not that commercial. And I like to laugh.” He smiles. “I’m a clown.”

‘Hit Man’ is out now on Netflix