Crews face 'complex case' rescuing entangled North Atlantic right whale in St. Lawrence

Mackie Greene is hoping that by Wednesday, a one-and-a-half-year-old female right whale that's been stuck in fishing gear for weeks will finally be free.

The director of whale rescue for the Canadian Whale Institute and lead disentangler, Greene has been following the calf across much of the Maritimes and eastern Quebec.

On Tuesday, Greene and his colleagues from the Campobello Whale Rescue Team (CWRT) drove seven hours from New Brunswick to Rimouski, Que., preparing for yet another attempt.

The whale, believed to be one of the calves of a 35-year-old female named War (ID number 1812) was first observed on June 22 off of New Brunswick, where she was already entangled in fishing gear.

During multiple attempts to cut it free of its ropes, a tag was attached to track the movement of the whale, which can travel great distances, even while under stress. The Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) is helping co-ordinate the follow-up operation.

According to Quebec's marine mammal emergency response team, Réseau québécois d'urgences pour les mammifères marins, the whale is still dragging metres of rope around its pectoral fins and in its mouth.

"We're getting to the end of what we can do for this whale," said Greene.

His team followed the whale to New Brunswick, up to PEI and their last attempt was off the coast of Gaspé, Que.

Equipped with big balloon buoys and poles, he says they first try to slow down the calf before cutting into the ropes.

"We have long sectional poles with sort of V-shaped cutters that once the whale gets tired, [then] when it comes to the surface we can stay a lot closer to the whale and reach out and grab one of the lines," said Greene.

A file photo, taken in 2018 off the coast of Plymouth, Mass., shows a North Atlantic right whale feeding. A young whale first observed on June 22 off of New Brunswick has moved into the St. Lawrence Estuary, dragging fishing gear in its pectoral fins and mouth. (Michael Dwyer/The Canadian Press/The Associated Press)

The rescues are not without risk. This particular whale is young, "pretty rambunctious" and her tail is free, making it more challenging to reach her and leaving rescuers vulnerable to getting slapped, says Green.

Wednesday marks the seventh anniversary of the death of Joe Howlett, Greene's colleague who was killed while freeing an entangled whale

"He was hit by the whale by the tail and was killed," said Greene.

"Whales aren't really aggressive, but they're just so big and they're scared and panicked and hurting and they're trying to get away from you as quick as they can. So when that big tail comes up and if that happens to hit the boat or hit anybody it would be all bad."

Calf at risk of starvation

According to observation reports from DFO air crews on July 8, the animal is swimming at a good pace and moving along the surface of the water.

"The faster we can free this animal, the better are the chances," said Robert Michaud, co-ordinator for the Réseau québécois d'urgences pour les mammifères marins.

"It's a complex case.… It often takes several attempts and it is very important for the survival of this animal that we are able to withdraw everything."

He says the weather is also not on their side, with the team facing foggy conditions as they catch up to the calf.

Composed of former fishermen and experts, Michaud says there are only two fully trained teams doing these rescues in the eastern part of Canada.

He says there's been a growing number of entanglements and collisions in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, even referring to the mammals as a kind of "climate change refugee."

"They used to be in large concentration in the Atlantic, and in the 2010s and on they moved inside the Gulf of Saint Lawrence," said Michaud.

Seeing how many calves don't make it past one or two years is heartbreaking, says Geneviève Peck, a master's student at the Marine Institute of the Memorial University of Newfoundland, who evaluates the suitability of different types of fishing gear for fisheries.

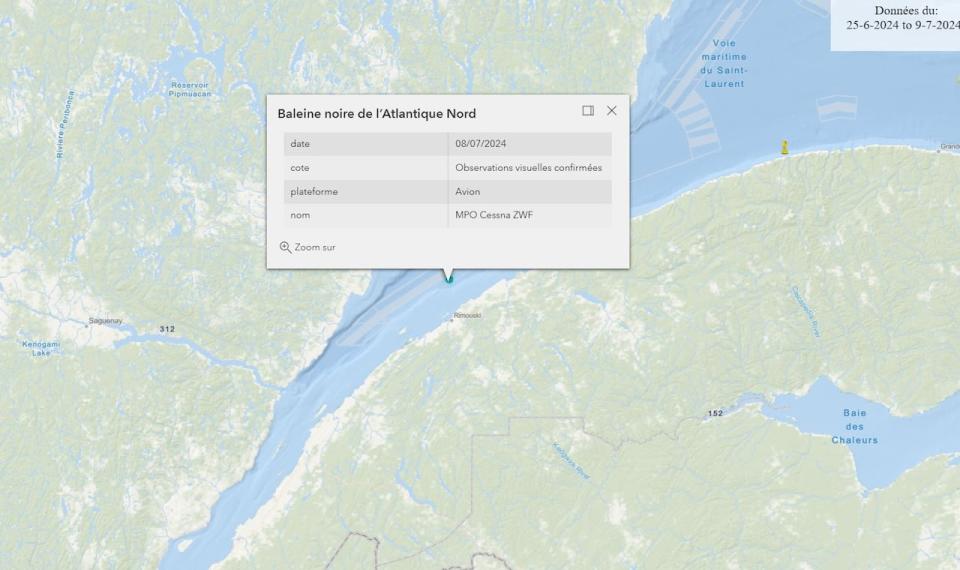

An interactive map from Fisheries and Oceans Canada confirms the observation of the right whale in the St. Lawrence Estuary on Monday. (Fisheries and Oceans Canada)

Having studied the North Atlantic right whale for the past couple years, she says the slow-moving animals tend to prefer staying in coastal waters where copepods — a type of crustacean — are abundant.

These warm, shallow waters are also where most of the fisheries tend to take place, she says.

"Snow crab and lobster gear are the most common types of gear that you find these whales entangled in," said Peck.

"Most of the entanglements happen around the head and the mouth. So if the whale isn't able to feed, it will just die very slowly. And that's another heartbreaking issue."

She says it can sometimes take whales six months to a year to die from an entanglement, which can also cause serious lesions.

"It's a really slow and painful death," said Peck.

Transport Canada is asking all vessels in the area to voluntarily reduce speed and not to exceed a maximum speed of 10.0 knots.

The Réseau québécois d'urgences pour les mammifères marins asks the public to respect a 400-metre distance with at-risk species.