Courtney B. Vance Shares Story of Father’s Suicide in Powerful New Book “The Invisible Ache ”(Exclusive)

Courtney B. Vance teamed up with Dr. Robin L. Smith to write about reclaiming Black men's mental health

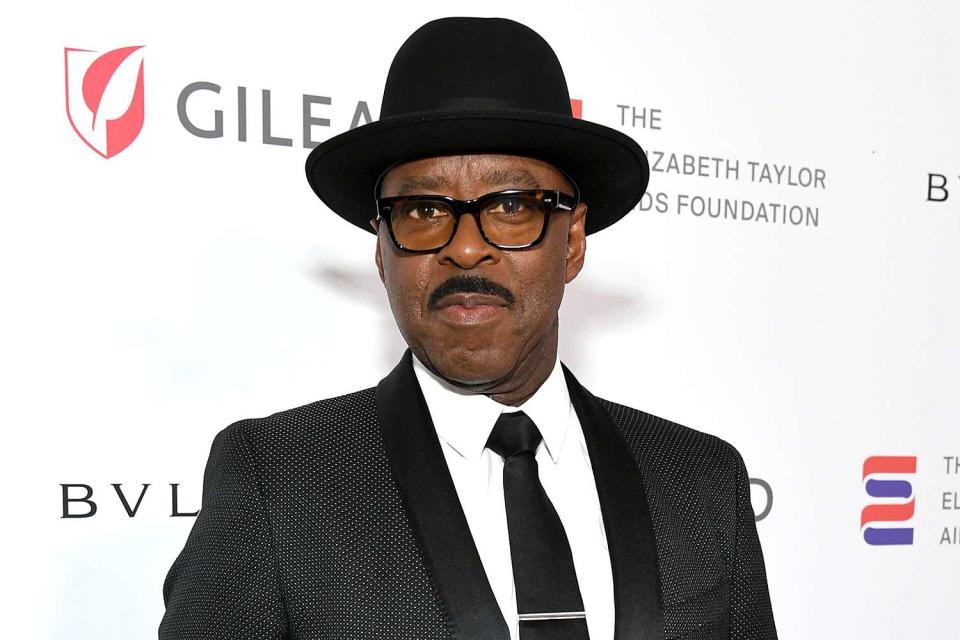

Jon Kopaloff/Getty

Courtney B. Vance in 2023Courtney B. Vance is sharing his deepest ache — and encouraging other Black men to do the same.

In the new book The Invisible Ache: Black Men Identifying Their Pain and Reclaiming Their Power, out Nov. 7, Vance teams up with fellow mental health advocate Dr. Robin L. Smith to create “a moving combination of memoir, psychology and practical tools,” per a synopsis.

The Emmy winner begins the book with the tragic story of his father’s sudden suicide, when Vance was 30 and starring in the Broadway play Six Degrees of Separation opposite Stockard Channing.

The painful reality of that loss — combined with the realization of his father’s long-held suffering and his mother’s subsequent mandate to seek a therapist — were the first steps of Vance’s journey toward acknowledging his own feelings.

“Sometimes there's no way through it but straight through it,” Vance, 63, tells PEOPLE. “You can't go over it, you can't go below it, you can't go around it. And if you do, you just delay the process.”

The Invisible Ache reveals those processes in vivid detail: how Vance grieves, heals, practices self-care and balances mental health with his family, including his wife Angela Bassett and their 17-year-old twins, Bronwyn Golden and Slater Josiah.

Related: Stars Who've Spoken Out About Their Mental Health Struggles

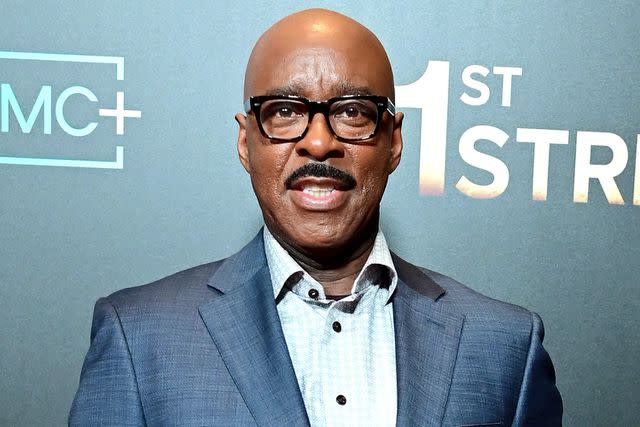

Shannon Finney/Getty

Courtney B. Vance in 2022Never miss a story — sign up for PEOPLE's free daily newsletter to stay up-to-date on the best of what PEOPLE has to offer, from juicy celebrity news to compelling human interest stories.

Smith, a psychologist and author who became The Oprah Winfrey Show’s “therapist-in-residence,” backs up the actor’s anecdotes with research and statistics about why mental health struggles today are a “pandemic,” as she says, for one demographic in particular: “Black boys and Black men are dying at a higher rate of suicide.”

The impetus for this book, she adds, is harnessing the fact that “our superpower is transparency and vulnerability.” By sharing stories like Vance’s about his father — excerpted below — the authors hope to provide a roadmap toward owning trauma to those who traditionally aren't encouraged to do so.

“If Black boys and men could grieve, if they could cry, if they could weep, then some of the domestic violence and violence towards self and others would diminish,” Smith tells PEOPLE.

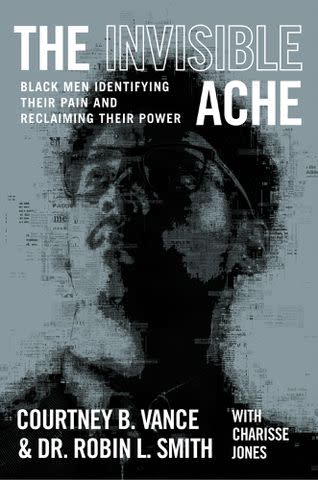

Nick Onken

Dr. Robin L. SmithVance says the book’s goal is to get even “one person from the brink to say, ‘If he can, where he was, begin to do the work, to take the steps, then maybe I can.’ ”

Also written with Charisse Jones, The Invisible Ache is a "guide for Black men navigating life’s ups and downs, reclaiming mental well-being, and examining broken pieces to find whole, full-hearted living,” as its synopsis states.

Read on for an exclusive excerpt of its opening essay, written by Vance.

Warning: The following contains potentially disturbing material.

Courtesy of Grand Central Publishing, Balance

"The Invisible Ache" by Courtney B. Vance, Dr. Robin L. Smith and Charisse JonesIt happened on a Wednesday.

I was costarring in Six Degrees of Separation, and the Vivian Beaumont Theater in Manhattan had been my second home for the last year and a half. I had a matinee that afternoon, another show to do in the evening, and a short break in between to catch my breath.

When the phone rang, I was lying in bed trying to shake off sleep and get my mind ready for my midweek hump. I fumbled for the receiver.

It was my mother calling. She was hysterical.

“Courtney!” she screamed. “It’s your dad! He’s dead!”

I leaped up.

“What?” I asked. “How?”

I was already reeling. But the words she said next nearly knocked me to my knees.

“He shot himself,” she said, her screams lowering to a hush. “I found him. In the TV room.”

There’s no map for where your thoughts go in a moment like that, when you learn someone you can’t imagine life without is now gone, not because he was snatched away by sickness or old age, but because he’d chosen to leave us, by his own hand.

Daddy kept his hurt to himself. Neither he nor my mother were ones to gripe or complain in front of their children. But there was an unease in the air, hovering in between all the words left unsaid. I would come home from school and Daddy would be downstairs in his office while Mom was upstairs in their bedroom. I would go back and forth between the two of them, trying to be a bridge, trying to mend something I didn’t understand but that I felt was broken all the same.

When I got the call that my father was dead and I flew home, I found my mother puddled up on the floor. It took a couple days for my sister to get to Michigan, so I nursed Mom’s grief and my own mostly alone. In the coming days, Mommy somehow gathered herself enough to call the funeral director, and during the homegoing ceremony she nodded her head through the hymns and eulogies and picked at her plate during the repast.

After the service was over, I wanted to run back to my life. School had been a gift from my parents, a responsibility I had to fulfill, but it was also my escape, a way to avoid whatever was going on in our home. Now, as I performed on Broadway, my career filled the same void. I wanted to get back to work and push the picture of my father’s casket so deep in my subconscious that I could hardly find it. I was ready to roar through, to rise higher, like I’d always done. Like my parents taught me to.

But where there had been four, there were now just us three. And my mother was ready to teach me something different.

I’d just finished packing my bag for New York when Mom called my sister and me into the living room and asked us to sit down.

“When you both get back home, I want each of you to go to therapy,” she said. “And I’m going to find me someone to talk with too.”

She didn’t want us to keep the pain a secret, not our father’s, not our own. You don’t want to wait until a tragedy happens to realize you’ve got stuff to get over. It took my father killing himself for me to recognize I had issues. We all do. And we’ve all got to figure out what those issues are, and face them. If we don’t, they will overtake us, stamp out our light, and leave a trail of broken hearts behind. One of those broken hearts will probably be your own.

My old way of coping, the escaping, the not dealing with, the rising above, had gotten me to the age of thirty. But after my mother found my father’s limp body, I learned the old ways had taken me as far as they could. I had to do something different.

I never realized I needed therapy. I didn’t even really know what therapy was. But my mother asked me to get some. And I always did what my mother and father told me.

“Okay, Mommy,” I said. “I’ll get some help.”

But how to begin?

Excerpted from The Invisible Ache by Courtney B. Vance and Robin L. Smith. Copyright © 2023 by Courtney B. Vance and Robin L. Smith. Reprinted with permission of Balance Publishing, an imprint of Hachette Book Group. All rights reserved.

If you or someone you know is considering suicide, please contact the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline by dialing 988, text "STRENGTH" to the Crisis Text Line at 741741 or go to 988lifeline.org.

For more People news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on People.