Court declares Sabah-born autistic stateless teen boy as a Malaysian, orders govt to issue MyKad

KUALA LUMPUR, Oct 18 — The High Court in Kuala Lumpur has declared a 15-year-old autistic boy — who was born in Sabah to a Malaysian father — as a Malaysian citizen, and has ordered the government to issue the child with a MyKad.

The boy is stateless, as the Malaysian government did not recognise him as a citizen, and as he is not a citizen of any country in the world. He has lived in Malaysia since birth.

Happy that her son is finally recognised as a Malaysian, the mother told Malay Mail: “A feeling that cannot be described with words, happiness mixed with sadness and gratitude to God, especially with our lawyer who has worked very hard for our case.

She said the priority would be registering the child with the Malaysian government for an “OKU card” or a card for persons with disabilities. Only Malaysian citizens can register their OKU status with the government.

“The first thing we will do after obtaining citizenship, we as one family will fly to Kuala Lumpur to meet with our lawyer and apply for an OKU card,” she said via the family’s lawyer.

The boy’s status as a non-citizen of Malaysia has resulted in multiple challenges, including having to pay higher hospital fees.

“It is truly very burdensome, each time dealing with the government hospital’s registration counter, the charges are for foreigners; not eligible to apply for OKU card and cannot attend government school as OKU card is needed. Besides that it is very difficult for us to bring him along anywhere due to the problem of not having an identity card,” the mother said, adding that she also suffered emotional distress due to this situation.

Malay Mail is withholding the name of the child and his parents for privacy purposes.

The boy won the court declaration that he is a Malaysian after he and his biological Malaysian father brought the government to court via a lawsuit filed about nine months ago.

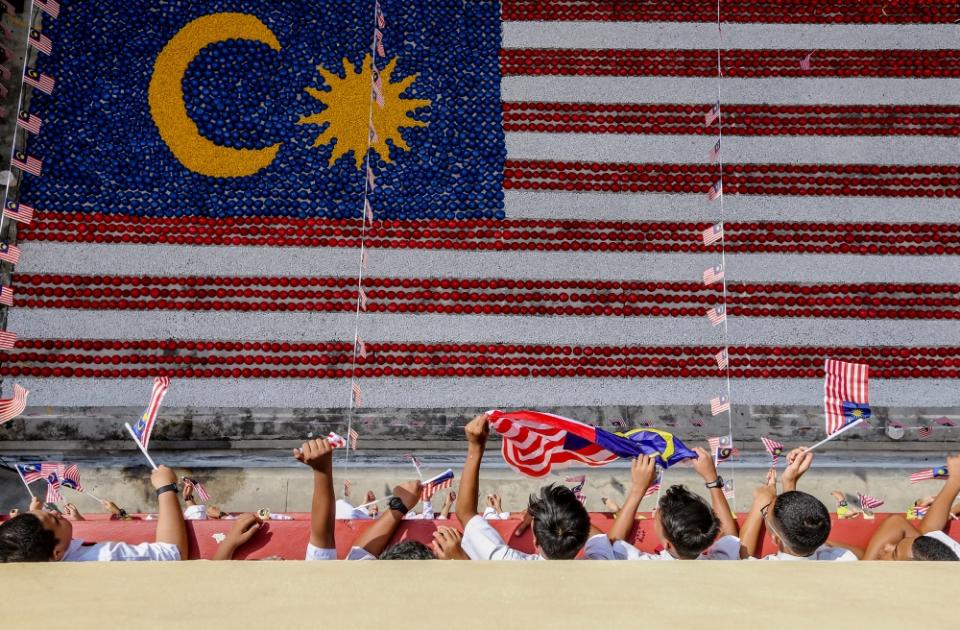

The boy’s 2008 birth was before the parents became legally married, and this would be the reason why the government refused to recognise the child as a Malaysian under citizenship laws in the Federal Constitution. — Picture by FIrdaus Latif

How did the boy end up stateless?

Based on court documents sighted by Malay Mail via a file search, the child was born in August 2008 at Hospital Likas in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah to his Malaysian father and his non-Malaysian mother. The mother, who is a citizen of the Philippines, was issued a Malaysian permanent resident card in May 2012.

The boy’s 2008 birth was before the parents became legally married, and this would be the reason why the government refused to recognise the child as a Malaysian under citizenship laws in the Federal Constitution.

In an affidavit or sworn statement filed in court, the father said an attempt to register his son’s birth with the Malaysian government in 2008 was unsuccessful due to the lack of a marriage certificate for the couple.

The couple could not be legally married until the father’s June 2013 divorce from his former wife.

In December 2013, the father became legally married to the child’s biological mother at the Sabah Islamic Religious Affairs Department (Jheains), which then issued a marriage certificate.

On April 4, 2014, the parents registered the boy’s birth with the National Registration Department (NRD). The boy was issued a birth certificate that stated his citizenship status to be “Bukan Warganegara” or not a citizen of Malaysia.

On February 22, 2017, the boy — who was due to turn nine that year — applied to the NRD for Malaysian citizenship under the Federal Constitution’s Article 15A.

But up until now, six years later, there is still no decision from the NRD on the child’s citizenship application.

Article 15A comes with an age limit, as it empowers the Malaysian government to register anyone aged below 21 as a citizen when there are “special circumstances”.

After years of waiting without any outcome on his citizenship application, the boy and his father on February 1 this year filed a lawsuit via an originating summons at the High Court in Kuala Lumpur. This was months before he turned 15.

The lawsuit named three respondents namely the national registration director-general, the Home Ministry’s secretary-general and the government of Malaysia.

In the lawsuit, the boy sought a court declaration that he is a Malaysian, as well as for other court orders such as the issuance of a MyKad and a new birth certificate stating him as a Malaysian.

According to the father, the boy had suffered mental and emotional distress when he started schooling as he was mocked by schoolmates for having a birth certificate stating that he was not a Malaysian, and the schoolmates also labelled him as a foreigner. — Picture by Sayuti Zainudin

How has being stateless affected the boy?

In November 2014, government hospital Hospital Duchess of Kent in Sandakan, Sabah diagnosed the boy as having an autistic spectrum disorder, as seen via his speech development and ability to socialise with others being affected.

But the parents could not apply for an OKU card from the Malaysian government for the boy as he does not have Malaysian citizenship, which means the autistic child cannot enter government special schools and access special therapy at government hospitals and has to pay high fees imposed on foreigners for hospital services, the father said.

The autistic spectrum disorder falls under one of the seven categories of disabilities that may qualify an individual to register with the Malaysian government as an OKU.

According to the father, the boy had suffered mental and emotional distress when he started schooling as he was mocked by schoolmates for having a birth certificate stating that he was not a Malaysian, and the schoolmates also labelled him as a foreigner.

The school would also question his son’s citizenship status every time a new school year began as he is stateless, the father said.

The father also highlighted that being stateless in Malaysia would result in his son facing difficulties in the future, such as furthering his studies at the tertiary level, opening a bank account, carrying out online transactions, obtaining a driving licence, and accessing medical treatment at government hospitals.

In court affidavits, national registration director-general Zamri Misman — on behalf of the three respondents sued — said the boy was stated to be “Bukan Warganegara” or not a Malaysian citizen, as the fact that he was born before his parents were legally married meant that child would follow the non-Malaysian mother’s nationality status.

(This is based on the government’s argument which applies Section 17 of Part III of the Second Schedule of the Federal Constitution when deciding on whether a person who was born out of wedlock in Malaysia is entitled to Malaysian citizenship. The government’s position is that Section 17 means that such persons — who are born locally before their Malaysian father and non-Malaysian mother are legally married — are not entitled to take the Malaysian father’s citizenship but will have to adopt the non-Malaysian mother’s citizenship from her country of origin.)

Through the affidavits by Zamri and submissions to the court by the Attorney General’s Chambers’ (AGC) senior federal counsel Nur Irmawatie Daud, the government argued that the boy was not stateless as he was allegedly eligible to obtain citizenship from the mother’s country — the Philippines.

But the father produced in court a March 6, 2023 document from the Philippine Embassy in Kuala Lumpur, which certified that the boy’s birth has never been reported to the embassy and has never applied for a Philippine passport from the embassy.

The father cited the embassy document as proof that his son is stateless and that his son has not obtained citizenship from the Philippines, later also reiterating that the child is not a citizen of any country.

Last Wednesday, High Court judge Datuk Wan Ahmad Farid Wan Salleh declared the boy as a Malaysian citizen according to the Federal Constitution’s Article 14(1)(b) and Section 1(a) of Part II of the Second Schedule.

The High Court also ordered the government to issue the boy with both a MyKad and a new birth certificate to state that he is a Malaysian citizen, within 30 days of the court order. There was no order made to costs.

Lawyer Larissa Ann Louis confirmed that the High Court judge had said that the NRD recognised the boy’s biological father as stated in the child’s birth certificate and hence the child had fulfilled the Section 1(a) requirements to be a Malaysian citizen. — Picture by Miera Zulyana

The boy’s lawyer Larissa Ann Louis confirmed to Malay Mail that the judge had said the High Court was bound by the Federal Court’s November 2021 decision in a citizenship case dubbed the CCH case. In that case, the Federal Court had adopted the reasoning in an earlier Federal Court minority decision in May 2021 (in another citizenship case known as the CTEB case) which stated that Section 17 is a supplementary provision to close any gaps or to resolve technicalities that may arise when the person’s own birthplace or their parents’ identity is an issue.

Larissa also confirmed that the High Court judge had said that the NRD recognised the boy’s biological father as stated in the child’s birth certificate and hence the child had fulfilled the Section 1(a) requirements to be a Malaysian citizen.

In order to automatically be a Malaysian, Section 1(a) requires persons born within Malaysia to have at least one parent who is a Malaysian or a permanent resident at the time of the person’s birth.

Previously, Larissa had in her submissions to the court cited the Federal Court’s CCH decision which found that provisions like Section 17 is meant to help with the interpretation of other citizenship provisions in the Federal Constitution instead of to place conditions. She had also argued that Section 17 does not apply to the 15-year-old boy’s case and that he is entitled to take on his Malaysian father’s citizenship.

Besides expressing happiness for the 15-year-old boy, Larissa also encouraged others who are facing similar challenges.

“Every case won in court hits differently because it’s about different lives with different stories though coming from the same issue of law.

“I am happy that my client is a recognised citizen and will be able to finally apply for the OKU card, a card that would immensely help the family as a whole.”

“May this case give hope to those struggling, reach out. You are not alone,” she said.