Coral reef misinformation bubbles up amid bleaching worldwide

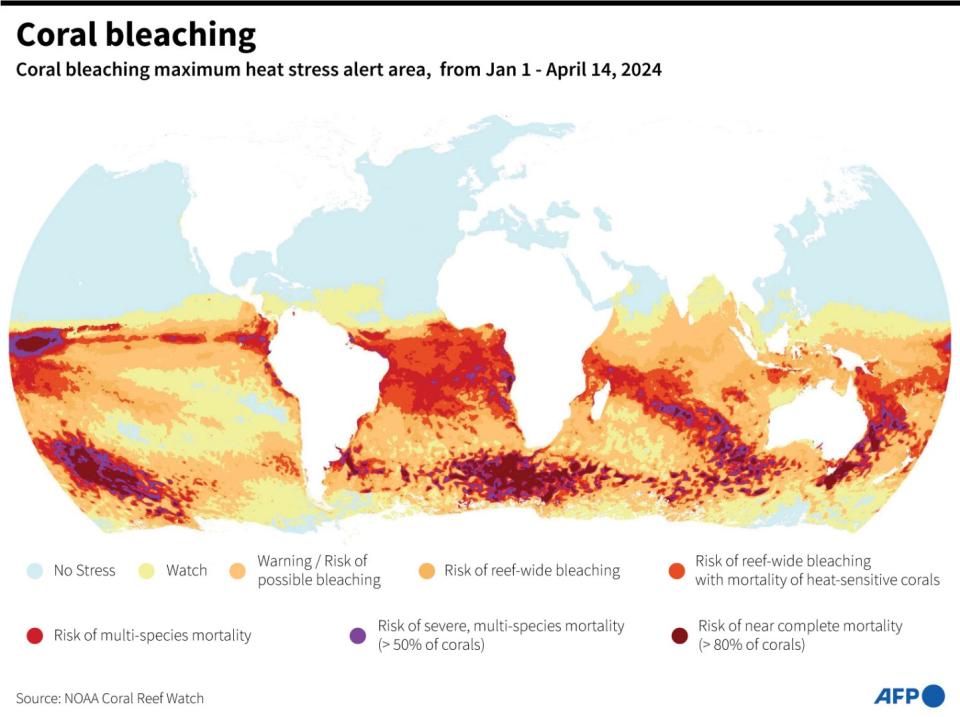

Australia's Great Barrier Reef experienced the most widespread bleaching on record in the summer of 2023 to 2024, with skeptics dismissing the role of human-induced climate change in putting coral barriers under intense heat stress. But scientists say ocean warming is the main cause for repeated, intense bleaching over recent decades.

"Coral bleaching is a natural phenomenon that's been happening for eons. That climatards believe it's unprecedented or catastrophic ~ just because we are witnesses in real time ~ only demonstrates how delusional and narrow-minded they are," an April 16, 2024 post on X says.

Similar claims spread elsewhere, claiming people are "weaponizing weather to dishonestly blame coral bleaching on a climate change."

An April 14 post adds: "Ever since the massive coral bleaching during the 1998 El Niño, the climate change ambulance chasers, are quick to cherry-pick bleached regions as evidence of a climate crisis."

Bleaching occurs when water temperatures rise and coral expel microscopic algae, known as zooxanthellae, to survive.

Australia's Great Barrier Reef experienced its worst bleaching event on record during the summer months of 2023 to 2024.

Posts that dismiss the role of human-induced warming in harming the reefs are inaccurate, scientists say.

"The statement that bleaching is being triggered by natural sources is unfounded, and in fact at this point of climate change, a ridiculous and frankly dangerous claim," University of Victoria marine ecologist Julia Baum (archived here) told AFP on April 17.

"While it is true that an individual coral colony could bleach if exposed to unfavorable (weather) conditions, the widespread coral bleaching that we are now witnessing -- across coral reefs around the world -- is being directly caused by climate change," she said.

Often dubbed the world's largest living structure, the Great Barrier Reef is a 1,400-mile-long expanse, home to a stunning array of biodiversity including more than 600 types of coral and 1,625 fish species.

Scientists observed that extreme bleaching -- when more than 90 percent of coral cover on a reef bleaches -- occurred in all three regions of the Great Barrier Reef (archived here). The phenomenon is tied to ocean temperature records, they say (archived here).

Increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases heat oceans and in turn warmer seas strongly affect the reefs' health, making them one of the most vulnerable ecosystems to climate change (archived here).

Impact of El Niño

El Niño is a natural cyclical climate pattern, which warms the sea surface in the Pacific Ocean, leading to hotter weather globally (archived here). Occurring every 2-7 years, the current El Niño emerged in June 2023, according to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and was weakening as of April 11, 2024 (archived here and here).

The recent bleaching events are not happening because of El Niño alone, said Sara Cannon, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Institute for Oceans and Fisheries, at the University of British Columbia (archived here).

"The baseline sea surface temperatures are higher because of human-driven climate change, and El Niño amplifies these already high temperatures further, resulting in reefs experiencing greater heat stress overall," she said on April 17.

Terry Hughes, director of the Australian Research Council (ARC) Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies (archived here), said that scientists are also observing warming under other weather conditions .

"In 2022, for the first time we saw mass coral bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef during the La Niña phase of ENSO cycles -- we no longer need an El Niño event to trigger mass bleaching," he said on April 17.

Sarah Davies, an assistant professor for the Marine Population Genomics Lab at Boston University (archived here) agreed that the coral bleaching events happening globally are unprecedented.

"The devastation caused in the Caribbean, Brazil and now throughout the Great Barrier Reef etcetera, will likely go down as the most devastating blow to coral reefs recorded," she said on April 18.

Fragile recovery, multiple threats

Bleaching does not automatically kill corals, Sarah Bedolfe (archived here), a marine scientist at the non-profit organization Oceana, explained. "If the corals are otherwise healthy and temperatures return to normal, given enough time, the corals may sometimes recover," she said on April 18.

But repeated bleaching, coupled with continued pressure from other threats including overfishing (archived here) and pollution (archived here) will cause mass coral mortalities around the world, she said.

A 2020 report by the United Nations Environment Programme found that between 2009 and 2018, about 14 percent of the coral worldwide was lost, as the interval between each mass bleaching event was insufficient to allow reefs to recover (archived here).

ARC's Hughes said: "Hundreds of millions of corals have already died from heat stress this summer," and reefs could not recover as the gap between recurrent mass bleaching and mortality events is shrinking.

"We had a 14-year gap on the Great Barrier Reef between 2002 and 2016, compared to five events in less than a decade (2016, 2017, 2020, 2022, and now 2024)," he said.

Marine biologist Anne Hoggett (archived here), who has lived and worked on Lizard Island (archived here) in northeast Australia, for 33 years, said when she first arrived, coral bleaching only occurred every decade or so.

Now, it is happening every year, she told AFP, with about 80 percent of vulnerable Acropora corals on the island reef suffering bleaching this summer.

"We don't know yet if they've already sustained too much damage to recover or not," Hoggett said.

AFP has debunked other claims about Australia's Great Barrier Reef and the impact of El Niño on ecosystems.