‘Copa 71’ Review: Women’s Soccer Documentary Uncovers Lost Tournament

If you’re a fan of soccer – or, in most of the world, a fan of the game they know as football – you probably recall some details from this year’s FIFA Women’s World Cup tournament held in Australia and New Zealand. If you’re a follower of the Spanish women’s team, for instance, you no doubt remember that they beat England to win the tournament; if you root for the U.S. team, you probably remember (but want to forget) that they barely made it out of the first round and were eliminated in the 16th, becoming the first defending champion not to make the semi-finals.

But fan or not, you likely know nothing at all about the 1971 Campeonato de Fútbol Femeni, known unofficially as the 1971’s Women’s World Cup. At the beginning of “Copa 71,” a documentary about the tournament that screened Thursday on the opening night of the 2023 Toronto International Film Festival, U.S. women’s soccer star and two-time World Cup winner Brandi Chastain watches footage from the tournament on a tablet and shakes her head.

“This is unbelievable,” she says. “Why didn’t I know of this?”

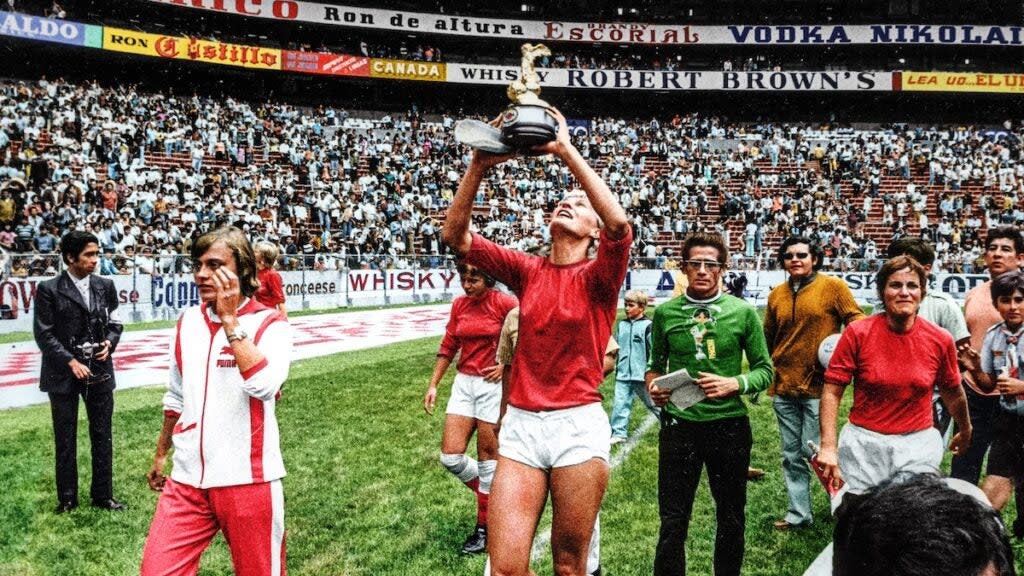

The goal of “Copa 71,” directed by Rachel Ramsay and James Erskine and executive produced by Serena and Venus Williams, is to make sure more people do know of this – this being the event that drew the largest attendance ever for a women’s sporting event, more than 110,000 for a match in Mexico City’s Azteca Stadium.

You can look at “Copa 71” as the “Summer of Soul” of women’s athletics – the chronicle of a big event that took place more than 50 years ago and had been lost to time, making use of copious footage that has remained unseen for most of that period. The football footage may not be as instantly rousing as the concert footage in Questlove’s Oscar-winning documentary, but the “Why didn’t I know of this?” will likely be the reaction of a great many viewers.

The film is a straightforward mix of archival footage from both on and off the pitch, interspersed with talking-head interviews with commentators and, crucially, players from most of the key teams in the 1971 tournament: Carol Wilson from England, Ann Stengard and Birte Kjems from Denmark, Silvia Zarazoga from Mexico, Nicole Mangas from France, Elena Schiavo from Italy.

Almost all of them describe growing up in an era in which the idea of women playing football was widely dismissed, mocked and even outlawed. Zarazoga said she’d play all day but stop before her dad came home because he’d beat her if he caught her. Schiavo was sent to sewing school and lasted all of one year until she quit. And when England reluctantly ended a 50-year ban on women’s football teams, one British TV announcer dismissively said the country’s football association “has been nagged into allowing women’s teams to play,” while another commentator called the notion “a curiosity, both comedic and erotic.”

But for Mexico, hosting the 1970 men’s World Cup had been such a success that the country considered it a business opportunity to stage an event with the world’s top women’s teams. The ruling body in men’s soccer, FIFA, didn’t control the women’s sport and thus didn’t recognize the 1971 event as a true World Cup, objecting to the use of the name and going so far as to force women play in the smaller Mexican stadiums that they controlled.

That move from the famously corrupt FIFA backfired, because it meant the 1971 tournament had to move to the country’s biggest venues. And to fill places that size, the organizers had to do lots of promotion, including the encouragement of “costumes as close as possible to hot pants.”

Apparently, it worked. When the players landed at the airport in Mexico City they were astonished to find to find reporters, photographers and fans waiting for them. “We landed in a world that we didn’t know,” says Wilson.

The action is set to needle drops of female empowerment anthems of the day, including Kiki Dee’s “I’ve Got the Music in Me” and, of course, Nancy Sinatra’s “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’.” The filmmakers are able to draw from a wealth of little-seen footage from the tournament. In the early going, Italy played well, led by the fiery Schiavo; England, one of the pre-tournament favorites, took success for granted and bombed out in the first round in an unexpected exit that may sound familiar to fans of the current U.S. women’s team; and Denmark played with unprecedented precision and breezed through to the finals.

Then there was the home team, Mexico, from which nobody expected much. They beat Argentina in the first game, easily muscled past England in the second, and beat Italy 2-1 in a controversial semifinal that found two Italian goals disallowed in the final moments before the referees ended the match 10 minutes early because of the riotous conditions in the stadium.

But the chaos of that game was only a prelude to a final week that found the Danish players moving to private homes after Mexican fans surrounded their hotel and made noise all night. The Mexican team, meanwhile, was accused in the press of refusing to play unless they were paid commensurate with their value and with the men’s game.

The mixture of exploitation, sexism, money and politics will sound familiar to anybody who’s followed women’s sports in recent decades, but placing it in the context of 52 years ago makes it something of a shock. The film whips everything up into an entertaining concoction that sometimes leaves the details a little hazy. (Half a century later, nobody’s quite sure if the Mexican team was making those demands or if the press was blowing things out of proportion.)

And the aftermath of the tournament brought more shocks, most of them unpleasant to the athletes who returned from scenes of adulation to be ignored and mocked at home. “We arrived at the airport,” says Wilson of the English team’s return home, “and I can’t remember one photographer. We never spoke about it.”

It would take decades for the women’s game to gain some respect and the final stretch of “Copa 71” spends lots of time going back and forth between the past and current eras, with comments from recent players Chastain and Alex Morgan, along with a speech by Megan Rapinoe used to drive home the point less directly.

At a breezy 90 minutes, “Copa 71” makes its case succinctly, dropping interesting tidbits while letting the event itself serve as a revelation. That event, by the way, is still not recognized as an official World Cup by FIFA, which now has authority over women’s football and didn’t begin its official women’s World Cup until 1991. “I’m ashamed that I knew nothing about this incredible tournament,” says Chastain. “This was intentional, to hide women’s football.”

“Copa 71” is a sales title at the Toronto Film Festival.

The post ‘Copa 71’ Review: Women’s Soccer Documentary Uncovers Lost Tournament appeared first on TheWrap.