How I Confronted My Own Childhood Trauma with Jewel Through Her Art Experience (Exclusive)

PEOPLE senior reporter Danielle Bacher — who sat down with the singer and mental health advocate — writes about her own experience at The Portal: An Art Experience

Courtesy of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

Jewel posing at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, 2024.When Grammy-nominated artist Jewel told me I'd be discovering myself through her new art exhibit, The Portal: An Art Experience by Jewel, I panicked.

I'm a writer who tells other people's stories. But for decades I struggled to communicate my own emotional and psychological pain from childhood. I suffered anxiety and depression in my adolescence, was forced on medication and at one point had given up hope and even contemplated suicide.

Avoidance became comfortable. But as I pushed through the foray of visual art this past weekend, I gained enough courage to publicly share my story — all because of Jewel.

Shane Drummond/BFA.com

Jewel featured at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, May 3, 2024.For her, the self-curated, 90-minute immersive experience at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art (open until July 28 in Bentonville, Ark.) represents the "three spheres" of existence: the inner realm, which is our thoughts and emotions; the physical realm, which includes our jobs, finances, families and nature; and the unseen realm, which humans have been trying to define since the dawn of time.

Related: Jewel Has Finally Found True Love. And You'll Be Surprised Who It Is (Exclusive)

As I began my journey at the exhibit, a hologram of Jewel, created by ProtoHologram, welcomed me inside, offering to guide me through the "seen" and "unseen" worlds of life and how they intersect. She encouraged everyone to speak their truth and bare their souls. Luckily, Jewel was also there in real life, helping all of us in the exploration and, in my case, unpacking painful memories.

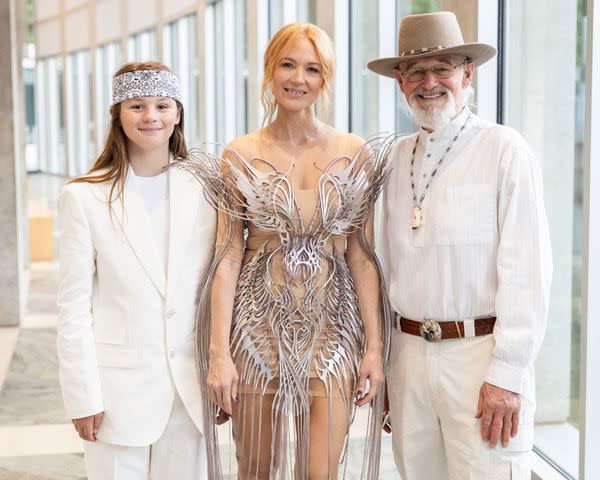

Shane Drummond/BFA.com

Jewel's son Kase (left), Jewel (center) and Jewel's father Atz Kilcher (right) at The Portal exhibit, May 3, 2024.Although I don't have exactly the same story as the singer — who detailed in her 2015 memoir that she was raised by her alcoholic and abusive father, Atz Kilcher, after her mother Lenedra Carroll left the family when she was 8 — I similarly struggled after my parents' traumatizing split in 2003 when I was 17. (Jewel and her father reconciled when he was in his 60s.)

I have a relationship with my parents now, but it's complicated, and I've had to learn to trust my decisions as I navigate a new territory of forgiveness.

Shane Drummond/BFA.com

Jewel's son Kase (left) and Jewel (right) at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, May 3, 2024.In 2014, after 16 years together, Jewel and rodeo star Ty Murray, announced their decision to divorce. "It's hard to know you're going to hurt your child's heart. And when you're going to inflict hurt on them, that's really painful," Jewel, 49, told me about how the split impacted their son Kase, 12.

Related: Ty Murray on His Divorce from Jewel: 'We Are in a Really Good Spot'

"It was working through just forgiving myself and lots of healing around that. But also, just knowing none of us are going to protect our children from all the hurt in the world, and so, how do we equip our children to handle hurt?" she said.

Her words resonated. After the divorce, Jewel began seeing a therapist. Her focus shifted to healing herself and protecting her son from more emotional baggage. "It's our job and our duty as divorced parents to make sure we're doing the best of our ability and not inflicting harm or letting anger get involved," she said. "We owe our kids that, if we can."

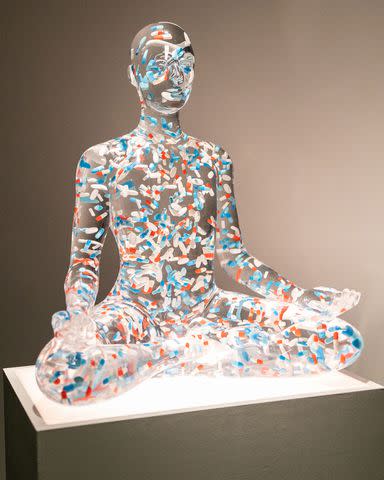

Unlike Jewel, my parents never shielded me from their heartache as they navigated their divorce. Walking through the exhibit, I traced the fear, pain and self-esteem issues stemming from my childhood in the 10 pieces of artwork — including an oil painting she created of her son and a sculpture titled "Chill," made from clear acrylic sheets with high-optical clarity (to reflect on the interpretation of meditation and medication) — Jewel hand-selected for the museum's contemporary wing.

Shane Drummond/BFA.com

"Chill" sculpture Jewel created for Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, May 3, 2024"I got a call a year ago from Jewel saying she's interested in working with the museum. She started asking questions about the possibility of creating an experience with us," Rod Bigelow, the executive director of Crystal Bridges, tells PEOPLE. "We are founded on the idea of disruption and innovation, and doing things differently to widen our audience. My answer to her was, why not? Since then, I think it's been a lot of trial and error and seeing her grow and evolve into this space. With the help of our team, she has been such a force."

At the exhibit's VIP opening on May 3, the singer reflected on the "warmth" she felt during her first visit to the museum a decade ago. "And when I wanted to do this art exhibition, I only wanted to do it here. It's the only place I really wanted this to be, and so Rod has been kind enough to keep working with me until we got the Portal to be here," said Jewel, who now lives in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado.

Related: Jewel Is a Work of Art Herself at Her Exhibit Preview

In the space, I started with the first two pieces of the collection: Kenny Rivero's Ezekiel's Wheel (made from oil on canvas in 2021), which refers to a biblical prophetic vision that perhaps symbolizes this world to the afterlife.

Shane Drummond/BFA.com

Genesis Tramaine, 2020 Evidence of Grace (detail) at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, May 3, 2024.Next, Evidence of Grace, a 2020 painting by artist Genesis Tramaine, sets two abstract, graffiti-like figures against a vivid green background using acrylic and oil pastel. The faces, eyes and other limbs that emerge from the composition are disorienting, and the piece helped me realize the struggles I have in admitting how I really feel.

Like the Billy Joel song, my brother Randy, who has autism, and I grew up in Allentown, Penn. The song was the lead track off 1982's The Nylon Curtain, in which the Piano Man sang about a collapsing mining city in Pennsylvania where the American Dream had died hard.

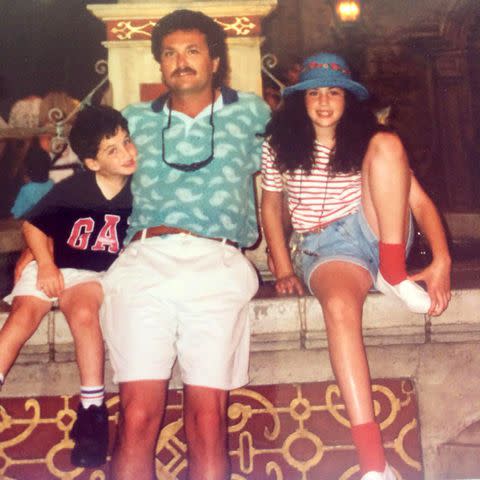

Danielle Bacher

Randy Bacher (left), Gary Bacher (center) and Danielle Bacher.My brother's childhood in our hometown was rough, filled with bullying and loneliness. Our father, Gary, resembled Terry Kiser in Weekend at Bernie's, except with a pulse. Back then, he was the kind of businessman whose attention you wanted but learned to regret.

He would play 18 holes of golf while our mother, Feryn, a registered nurse, would gossip poolside with all the bikini-clad mothers. My brother splashed around in the warm water while kids shouted, "Stupid!" and "R----d!"

Randy has what is officially called PDD, or pervasive developmental disorder, a condition whose symptoms vary enormously — hence the term "spectrum" — but is generally characterized by delays in the maturation of socialization and communication skills, along with mild cerebral palsy and attention deficit disorder.

Danielle Bacher

Siblings Randy Bacher (left) and (Danielle Bacher (right) in 2023.When kids mocked him, he would try to keep his composure but often got annoyed, shouted back and ended up hysterical and in tears. I'd comfort him, which probably made the ridicule worse, but I couldn't bear to see him suffer.

As I ventured over to the fifth piece of artwork by Mickalene Thomas, titled Guernica (Resist #3), featuring rhinestones, acrylic and oil on canvas mounted on wood panel, I learned the artist uses imagery from civil rights and Black Lives Matter movements. While I studied the piece, I wrote in a reflection journal about the conflict in my life.

During our childhood, my parents were constantly fighting about money and my brother. I'd endure emotional abuse during our father's drunken rages, and he'd often criticize Randy while yelling at him. My mother was also sometimes intoxicated, emotional or unruly herself.

After my 17th birthday, our parents sat us in their bedroom. Our father told us that he was moving out. My brother cried, and he pounded his head with his fists, trying to drive out the emotions. I was devastated, but I had secretly hoped my parents would end things. The tension was killing us all.

Our parents officially separated and filed for divorce. Randy didn't know what love was; by the time he was old enough to understand, our parents despised each other. We were both grieving the loss of the only real relationship we knew.

Related: Jewel Reminds People They Are Not Alone for the Holidays

A few weeks after my father left us, things reached a breaking point. My brother was home for summer break from boarding school for kids with learning disabilities. Our father stumbled in late at night, throwing everything he could get his hands on and screaming obscenities. He shouted in my face, and my mother defended me. I ducked out of the way and took cover.

Afterward, my mother filed a restraining order against him — and we didn't speak for almost two years. I started acting out, using alcohol and sex to cope, and I was forced on antidepressants and battled an eating disorder, just like Jewel. But what hurt most was that I couldn't be there for my brother, and the guilt ate away at me.

In 2008 Randy had reached his breaking point. Struggling in his personal life and with our parents' divorce, he was sent to a psychiatric-care unit for 10 days after threatening suicide. By then I had moved to Los Angeles. I wished so badly I could be there with him but knew there was little I could do from so far away.

Wesley Hitt/Getty

Jewel attends The Portal: An Art Experience By Jewel, May 3, 2024.After making my way to Jewel's artwork, I learned that she once caressed Bob Dylan's nose in hopes of sculpting it. As the singer tells it, she always had interest in visual art and perhaps could have been a full-time artist had she not been discovered by a record executive while playing at a coffee shop in San Diego in the early '90s.

"Bob Dylan believed in me," says Jewel, who began carving marble and working with clay in high school. "I thought, 'Okay, you know what? If he's the only one, I'm good.' He spent every single night in the dressing room one-on-one going through my lyrics asking me why I wrote them. He told me, 'Don't stop. Keep going.' It makes me cry talking about it."

Courtesy of Jewel

Jewel's portrait of her son Kase, 2024.While taking in the portrait of her son (she made it following a two-week oil painting class last spring in Rome), I had a deeper understand of something she had told me during our interview. "Kids of abuse probably suffer longer than maybe other people because you don't want to let go of the fantasy that you wanted — the perfect family — and you don't want to fail, which I think is something everybody can relate to," she said. "...And then just knowing that there are certain things that would make the best of a hard situation, which is healing."

My brother and I had a difficult situation. We had unrelenting feelings of low self-esteem, and I believe it's because our parents failed us. Their love wasn't good enough. And truthfully, my love for Randy was never enough. But as Jewel relayed, well-being is a side effect of everything working together in harmony. Healing takes time.

In her 30s, Jewel discovered her mother, who used to manage her career, embezzled over $100 million from her, she alleged on a 2023 episode of the Verywell Mind Podcast. "Our relationship messed with my head so much. It was so much psychological abuse that I was afraid to let a therapist get close to me," she told me. "Not all of us get the storybook ending, and that's okay. We can still heal." (The singer and her mother haven't spoken since 2002.)

Shane Drummond/BFA.com

Fred Eversley, Big Red Lens, 1985 at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, May 3, 2024.Related: How Mindfulness Saved Jewel When She Was Homeless — and Why She's Sharing Her Practice Now

One of the final pieces in the exhibit, the Big Red Lens (created by Fred Eversley in 1985), combines light, science and metaphysics. For Jewel, it represents all three spheres unified. Just then, it hit me that I am unwilling to confront the people who have hurt me in the past. Pain can beget more pain.

Shane Drummond/BFA.com

Jewel's drone show at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, May 3, 2024.Ultimately, I grasped that my pain was caused by repressed emotions. While my healing journey is certainly ongoing, I believe the exhibit unearthed my feelings and paved the way to begin the path towards reconciling the anger, insecurity and worry I've long held inside.

Jewel taught me the most valuable lesson, one she learned herself through decades of experience. I'm not asking or seeking forgiveness from my family, but I'm choosing my path toward happiness and growth. I finally let go.

For more People news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on People.